In August, Columbophile posted initial details for a July 2018 ColumboCon in Ossining, New York. These plans included a “Columbo mystery-writing competition.”

What that entails exactly, we do not know. But it suggests that Columbo fans will be solicited to submit their own Columbo stories and scripts – a very enticing prospect.

If so, how do you go about writing a Columbo? This is a subject to which I have given considerable thought. Here are the five key steps I think you need if you want to craft the perfect Columbo.

Step 1 – The perfect villain

Abigail Mitchell has many of the qualities we seek for in a ‘perfect’ Columbo killer

We are all familiar with the typical Columbo villain: accomplished in a respected field, supremely self-confident, and quick-witted. Some are rich, all are successful. Some are arrogant, none suffer fools lightly. Some are smart, others are really smart.

But the perfect Columbo villains also have a streak of conscience that ultimately makes them somewhat likeable. They didn’t do what they did because they wanted to; they did it because they felt they had to. Adrian Carsini (Any Old Port in a Storm), Col. Lyle Rumford (By Dawn’s Early Light), Tommy Brown (Swan Song), Abigail Mitchell (Try and Catch Me), and Oliver Brandt (The Bye-Bye Sky High I.Q. Murder Case) come immediately to mind.

There is a reason why, by the end of these episodes, Columbo empathises with each of these villains, perhaps even respects them. “Not for what they did, certainly not for that,” as Columbo explains in Try and Catch Me, “But for that part of them which is intelligent or funny or just nice.” And that respect is mutual. Carsini respects how much Columbo has learned about wine. Rumford respects Columbo as a man of convictions. Mitchell respects his doggedness. Brandt thinks him far more intelligent than he is willing to admit.

“Perfect Columbo villains also have a streak of conscience that ultimately makes them somewhat likeable.”

So the perfect Columbo villain never acts purely out of greed or desire. Carsini, Rumford, and Brandt are desperately trying to keep everything they’ve ever worked for from slipping away. Brown wants his freedom. Mitchell wants her niece’s murder avenged. Each has been pushed to the limit.

Yet there is still one more element to the perfect Columbo villain: a flaw. And this flaw is what ultimately helps prove the case against them. Ken Franklin’s (Murder by the Book) flaw was that he was a mystery writer with, as Columbo said, “no talent for mysteries.” Adrian Carsini could not tolerate imperfect wine. Col. Rumford could not overlook a breach of discipline. Oliver Brandt couldn’t abide the notion that someone else might be smarter than he is. Dr. Marshall Cahill’s (Mind Over Mayhem) “flaw” is that he loves his son.

Notice, too, how each flaw figures in the villain’s motive as well: Franklin killed because, without his partner, he would be exposed as a fraud. Carsini killed so that his vineyard wouldn’t pass into the hands of “the 69-cents-a-gallon Marino Brothers.” Dr. Cahill killed to protect his son.

So choose a field you know something about. Create a leading light in that field. Give this person an enemy who has been working to, or is about to, destroy his or her world. And start thinking about what flaw could prove to be your villain’s undoing. Then move on to Step 2…

Step 2 – The perfect crime

Columbo has to dig deep to crack Harold Van Wick’s seemingly perfect alibi in Playback

While it is undeniable that many Columbo plots spring from a spontaneous crime (including William Link and Richard Levinson’s own script for Death Lends a Hand), the perfect Columbo requires a seemingly perfect crime.

For 15-20 minutes we see the villain putting this perfect plan in place: a murder disguised as a suicide (Étude in Black, Forgotten Lady); or an accident (The Most Crucial Game, The Most Dangerous Match, Swan Song, Try and Catch Me); or death by natural causes (A Stitch in Crime); or committed by kidnappers either known (Negative Reaction) or unknown (Ransom for a Dead Man, The Greenhouse Jungle) – or simply committed by someone else.

This last category usually requires a perfect alibi for the killer. This could entail a manipulated clock (Negative Reaction) or watch (Candidate for Crime), a rigged videotape (Playback, Fade in to Murder) or audio recording (Ransom for a Dead Man, Double Exposure, Exercise in Fatality), help from an accomplice (Prescription: Murder, Suitable for Framing, Double Shock, Publish or Perish, A Friend in Deed), or even from the unwitting victim himself (Murder by the Book).

“There are an infinite variety of possible perfect crimes and perfect alibis.”

Some Columbo alibis are more original than others. At the low end is the reset and smashed watch on the victim’s wrist in Candidate for Crime. At the high end is the elaborate Rube Goldberg device in Bye-Bye Sky High. And honorable mention must go to the two Columbos that somehow used the exact same false alibi technique: in both Suitable for Framing and It’s All in the Game (written by Peter Falk), an electric blanket is placed over the body to fudge the time of death. Once the killer’s alibi is established, an accomplice removes the blanket, fires a shot into the air within earshot of a witness, and flees.

Occasionally, the Columbo villain sets up the murder scene to make the killing look justified (Lady in Waiting) or like the killer himself was shot in the act (Old Fashioned Murder).

There are an infinite variety of possible “perfect crimes” and “perfect alibis.” And although none is truly “perfect,” the closer yours gets to that goal, the tougher it will be for Columbo to catch the killer and the more perfect your Columbo will be.

Step 3 – The perfect “click”

The non-working fountain in Nora Chandler’s garden: a fine example of a Columbo ‘click’

The fun of a great Columbo is Columbo’s prolonged interaction with the villain. So Columbo can’t waste a lot of time chasing down blind alleys before focusing his suspicions on the actual killer. Something must occur early on to “click” Columbo’s mental gears into place that our villain is indeed the killer. Not proof, certainly, or it would be a very short episode indeed, but a subtle clue that Columbo understands instantly.

Sometimes the “click” clue is simply something out of place, inconsistent with the picture we’ve been left to accept: the fresh water on the pool deck in The Most Crucial Game; the dead cockatoo in Étude in Black; the victim’s book in Forgotten Lady; or the inconsistency between the victim’s broken watch in Candidate for Crime and the rest of his attire. Or it is “a lot of little things,” as in Murder by the Book (“Little things. Driving back from San Diego on the day of the murder instead of taking a plane, the open mail, never showing any genuine emotion for a man that you worked with for 10 years.”).

“Sometimes the “click” clue is simply something out of place, inconsistent with the picture we’ve been left to accept.”

But a perfect “click” is one thing, and it doesn’t just point away from the cover story; it points toward our villain. The car radio setting in Blueprint for Murder points Columbo to a classical music buff. The burnt match in Mind Over Mayhem points Columbo to a cigar smoker. The pillow feather outside the hospital room in Troubled Waters points Columbo to the man inside. The turntable cuing in Bye-Bye Sky High points Columbo to the man who owns an identical turntable. In moments, the villain is squarely in Columbo’s sights.

And in the perfect Columbo, the “click” clue isn’t fully explained at the time Columbo spots it. That doesn’t happen until the end of the episode, where Columbo says: “It was just that music thing that bothered me. Carnegie Hall and Nashville. They don’t mix” (Blueprint for Murder); or: “They don’t use feathers in pillows in hospitals. They cause allergies. All the pillows in the hospital were made of foam rubber” (Troubled Waters); or: “That first day I couldn’t give a hoot in hell about a thief. I was lookin’ for a cigar smoker and there you were” (Mind Over Mayhem).

Further examples abound. “‘Why fountain doesn’t run?’ That bothered me. Yeah, that’s what started to bother me. Right. That’s what fountains are for. Why didn’t the water run? Most people like the sound of running water” (Requiem for a Falling Star); or: “You never should have let me read your palm. ‘Cause then I felt the ring and I felt the two diamonds sticking out and that raised rectangular border. That matched up with the cut on her cheek” (Death Lends a Hand).

Murder Under Glass features one of the best ‘click’ clues

Indeed, one of the best “click” clues is never discussed by Columbo until the final moments of the show. From Murder Under Glass:

Gerard: When did you first suspect me?

Columbo: Well, as it happens, sir, about two minutes after I met you.

Gerard: That can’t be possible.

Columbo: Oh, you made it perfectly clear, sir, the very first night, when you decided to come to the restaurant directly after you were informed that Vittorio was poisoned.

Gerard: I was instructed to come here by the police.

Columbo: And you came, sir.

Gerard: Yes.

Columbo: After eating dinner with a man that had been poisoned. You didn’t go to a doctor. You came because the police instructed you. You didn’t go to a hospital, you didn’t even ask to have your stomach pumped. Mr. Gerard, that’s the damnedest example of good citizenship I’ve ever seen.

Step 4 – Columbo-style banter

Paul Galesko’s critique of this discarded photo gives Columbo reason to suspect him

Now comes the fun part: the cat-and-mouse game. The little clues Columbo brings to the villain’s attention, either for an explanation or for the villain’s supposed expert advice. And once the villain explains or opines, there is always Columbo’s response laden with double meaning.

For example, in Death Lends a Hand, Columbo admits to Arthur Kennicutt that his investigation is at a dead end. So Kennicutt brings in Brimmer “to work on the case.” Columbo responds: “You know, I suddenly feel very much more optimistic about this whole thing.” A classic Columbo-style double entendre.

Columbo toys with his prey. Again in Death Lends a Hand, Columbo discusses with Brimmer several vital clues pointing to someone just like Brimmer as the killer, but concludes: “Isn’t that a coincidence? I’ll tell you, this case is just full of ’em.”

“Columbo will need a series of interesting, but non-definitive clues.”

In Troubled Waters, Columbo realizes that the killer must have had access to numerous duplicate keys, implying the use of a Curtis Clipper, a tool auto dealers use to duplicate missing keys. But instead of suggesting that this fact points to auto dealer Danziger as the killer, Columbo tells Danziger that he now wants to investigate all the auto dealers Danziger brought as his guests. A brilliant Columbo misdirection.

Or in Negative Reaction, when Columbo slips a Polaroid thrown away by the kidnapper in among pictures he is showing photographer Paul Galesko, adding: “Strange that Mr. Deschler would take this picture and throw it away. ‘Cause it’s a perfectly good picture.” This prompts Galesko to say: “Lieutenant, that is not a good picture. The exposure is way too light, the framing is off. Everything’s way off-center.”

But rather than pointing out what a revealing statement Galesko just made, Columbo responds: “I guess Mr. Deschler’s like you.” Galesko: “What do you mean, like me?” Columbo: “I mean, a perfectionist like you. Otherwise, why would he take another one?” Priceless Columbo banter.

Family ties provide Columbo with insights on a range of topics – including auto key cutting

And don’t forget the extended Columbo family. How did Columbo know about the Curtis Clipper in Troubled Waters? “My brother-in-law. He’s got an auto repair shop in the Valley. They bring in those wrecks. A lot of times they don’t have keys. He makes a key. He’s got a tool.”

Or – what excuse does Columbo give for snooping around Oliver Brandt’s accounting firm in Bye-Bye Sky High? “You see, I have this nephew, he’s studying to be an accountant. … And I said to myself, who could give me better advice to pass along to my nephew than Mr. Brandt?”

So Columbo will need a series of interesting, but non-definitive clues. If the clue requires the villain’s explanation, Columbo should ask for it. If the villain’s area of expertise includes the clue, Columbo should seek the villain’s expert advice. If the villain is someone Columbo ordinarily would update on new case developments, he may introduce it that way.

If none of the above applies, then see if Columbo’s nephew or brother-in-law might have a reason to implore the Liuetenant to ask the villain the all-important question.

Whatever the villain’s answer, Columbo should accept it as true – and add how strange it is that some people react completely differently to certain things than other people. Then have Columbo leave, pause, turn, and: “Just one more thing …”

Step 5 – The perfect “pop”

Columbo fabricates the ‘pop’ in Death Lends a Hand to snare Investigator Brimmer

Peter Falk himself branded the final, definitive Columbo clue, the one that proves the villain’s guilt, the “pop” or “pop clue.” It is the culmination of every Columbo episode so, naturally, a perfect Columbo must have a perfect “pop.”

As a general rule, all Columbo “pop” clues fall into one of three categories: (1) those Columbo finds that have been there all along; (2) those found or created by the villain in response to something Columbo said or did; and (3) the ones Columbo fabricates, in which case it is not the clue itself, but the villain’s reaction to the “pop,” that brings the villain down.

Clues that have been present, but undiscovered, since the beginning are probably the most difficult to pull off – because it’s often difficult to justify why this clue wasn’t investigated much earlier. In Dead Weight, why weren’t all of General Hollister’s guns collected and tested as soon as an eyewitness identified Hollister as the shooter?

“Why didn’t the police officers at Jennifer Welles’ house find Alex Benedict‘s carnation under the piano?”

In Lady in Waiting, why wasn’t Peter Hamilton’s first-hand account of which came first, the gunshots or the alarm, the first thing anyone scrutinised? In Étude in Black, why didn’t the police officers at Jennifer Welles’ house find Alex Benedict‘s carnation under the piano?

However, when this type of “pop” works, it can be something special – particularly if the “pop” long predates the villain’s commission of the crime. Jim Ferris’ five-year-old notes of the “perfect alibi” in Murder by the Book, is one example. The bullets Jarvis Goodland shot into “a pile of dirt” a year earlier (The Greenhouse Jungle) is another.

The “pop” also may be a by-product of the crime itself, such as the overheated wine only connoisseur Adrian Carsini can discern (Any Old Port in a Storm), or Edmund Galvin’s dying message in Try and Catch Me. And it can be a negative clue — the proverbial “dog that didn’t bark.” In Columbo terms, that might be the clock that didn’t chime (The Most Crucial Game), or the muleta that had no water stains (Matter of Honor).

The missing clock chime does in for Paul Hanlon in The Most Crucial Game

“Pop” clues in the second category are all the product of first-class Columbo banter. A classic example is the surgical gloves with powder burns in Troubled Waters. Columbo convinces Danziger that he cannot make out a case against Lloyd Harrington unless he can find surgical gloves with powder burns somewhere on the ship: if the fingerprint-free gun wasn’t thrown overboard, then the gloves Harrington used to keep his prints off the gun weren’t thrown over either; and no one packs ordinary gloves for a tropical cruise. So Danziger plants surgical gloves with powder burns, not realizing that he is leaving his own fingerprints inside the gloves.

Other examples are Dr. Barry Mayfield’s attempt to retrieve and hide the dissolving suture in A Stitch in Crime; Nelson Hayward’s shot from the terrace in Candidate for Crime; Riley Greenleaf fabricating a false book synopsis in Publish or Perish; Tommy Brown retrieving his parachute before Columbo’s search party starts looking for a missing thermos (Swan Song); Commissioner Halperin planting the stolen jewels in A Friend in Deed; and Columbo’s fateful dinner with Paul Gerard in Murder Under Glass.

Columbo’s banter pushes and pushes until the killer acts, leaving the “pop” behind. Nowhere did Columbo push harder than in Bye-Bye Sky High – prodding Oliver Brandt, minimizing the brilliance of his device, until Brandt has to prove his genius with a red magic marker.

“There is something unsettling, and thus imperfect, about a fabricated “pop.”

Category three is the most ethically challenging as it involves false evidence: the contact lens in Brimmer’s trunk in Death Lends a Hand; the cigar box in Short Fuse; the bead in the umbrella in Dagger of the Mind; the Shriner’s ring in Requiem for a Falling Star; the phony blind man in Deadly State of Mind; the fabricated photograph in Negative Reaction; the gun Columbo plants in the elevator in Make Me a Perfect Murder.

And while the visual scene prompted by these clues may be quite dramatic – Roger Stanford dismantling the cigar box is priceless – there is something unsettling, and thus imperfect, about a fabricated “pop.”

What is considered by many (including William Link and the Columbophile) the best Columbo “pop” clue doesn’t fit neatly into any of these categories. It’s the “pop” for Suitable for Framing. As Link describes it: “Falk’s fingerprints nails the murderer. Not the murderer’s fingerprints. It had never been done before and hasn’t since. The detective’s fingerprints nail the murderer.”

This entails Columbo touching the evidence at a key moment, but not fabricating anything. And while villain Dale Kingston plants this evidence, he doesn’t do so in response to Columbo’s action; he’d been planning this all along.

Nor is Kingston’s spontaneous reaction, upon learning of Columbo’s fingerprints and their significance, further proof of his guilt. He responds: “Uh, this is entrapment. It’s a setup, that’s all. You-you-you-you touched those paintings just now while I wasn’t looking. You saw him do it, didn’t you? You put your prints on those paintings while you were bent over watching them while they were working on it! He touched them.”

Dale Kingston goes through the emotional wringer at the conclusion of Suitable for Framing

In fact, that’s the reaction of an innocent man, not a guilty one. So Columbo pulling his gloved hands from his raincoat pockets – the part the Columbophile likes best – isn’t really the “pop.” It’s a terrific visual and a definite conversation ender. But it only proves that the actual “pop” – Columbo’s fingerprints on the paintings – is legitimate. It’s the icing on the pop, if there is such a thing.

Then again, the best Columbos often have a little coup de grâce at the very end. If it’s not Columbo’s gloved hands, it’s Columbo telling the killer just how early he’d been nailed: “about two minutes after I met you” (Murder Under Glass); the “first day” (Mind Over Mayhem); “right from the start” (Murder by the Book) – and why. It’s always nice to know that your perfect crime was a botched job from the start.

In conclusion…

From all accounts, Columbos were always extremely difficult scripts to write. That’s why some episodes are better than others, with even the poorer ones better than most other television shows. A perfect Columbo likely is as elusive as a perfect crime or a perfect alibi. But we can keep trying.

About the author

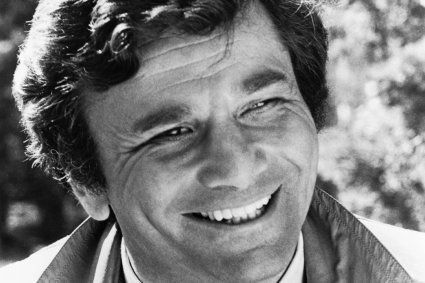

Richard Weill is a playwright, lawyer and former US prosecutor based in New York. A Columbo fan since the show first aired, he is an occasional guest contributor to the Columbophile blog

“Oh I’m sorry sir, there’s no such thing as a perfect Columbo. That’s just an illusion…”

Were I writing this article now, there is another item I would have added. It is this:

In the perfect Columbo, we know about the “pop” clue before Columbo does. If we pay attention, that is. It’s nothing obvious; it’s more of a teaser. “Teasing the solution,” I call it.

My two favorite examples are “Murder by the Book” and “The Bye-Bye Sky High I.Q. Murder Case.” In “Murder by the Book” it’s the brief scene, as Jim Ferris and Ken Franklin are driving near Franklin’s San Diego cabin, where Ferris says: “Do you ever get the feeling of deja vu? … Like you’ve done something before, but you know you haven’t? … I’m getting it right now. Isn’t that strange? I’ve never been here in my life.” In other words, Franklin’s “perfect crime” is something Ferris subconsciously remembers — because, as we learn later from Columbo, it once was a Ferris & Franklin plot idea.

In “The Bye-Bye Sky High I.Q. Murder Case,” the “pop” clue concerns how the red magic marker figured in Oliver Brandt’s Rube Goldberg-like murder contraption. Watch the opening minutes of the episode and pay attention to the red magic marker. We see it in Brandt’s attache case when he opens it and starts to unload the component of his contraption. We see him place it near the stereo. Later we see it on the floor. But we never see where Brandt ultimately places it, or how it figured in the crime. We’re teased with the idea that the red magic marker must have some key function, but left to wonder what that is.

There are myriad other examples: We get a long look at Paul Hanlon’s clock — and hear it chime — during the opening minutes of “The Most Crucial Game.” We know that Grace Wheeler’s film broke while she was murdering her husband in “Forgotten Lady.” In “Try and Catch Me,” we learn early on that victim Edmund Galvin pulled apart a manuscript while locked in Abigail Mitchell’s safe, which Abigail readily identifies: “That’s one of my manuscripts. The Night I Was Murdered.” Of course, in full, the title page would read The Night I Was Murdered by Abigail Mitchell, but we probably don’t consider that at the time.

In classic mystery writing, it’s called “playing fair with the reader.” That’s less of an issue in an inverted mystery like Columbo, where we see the murderer commit the crime. But it does make the solution that much more satisfying when the foundation for it was there from the beginning.

I just remembered another excellent example of “teasing the solution.” In the first few moments of “Troubled Waters,” Hayden Danziger reproaches his wife for neglecting to pack his golf gloves. [Later, Columbo unwittingly harkens back to this exchange when he remarks that his wife “didn’t pack any gloves. Now, I’ll bet Mrs. Danziger didn’t pack any either. Neither for herself nor for you. We’re going on a tropical cruise.

Who packs gloves?”]

Were these the gloves Danziger planned to use when murdering Rosanna Wells? Is this why he was looking for them. Was using surgical gloves only a fallback option? Too bad for Hayden, as golf gloves would have left no incriminating fingerprints on the inside. As Columbo said, “If the killer had worn leather gloves all we could hope for is powder marks. But surgical gloves, they’re different. The texture is different. The texture retains both fingerprints and palm prints.”

Gloves are the key to the “Troubled Waters” solution, and we’re given a teaser about this at the very beginning.

Very good article, fun to read and educational, too. Makes me want to sit down and write my very own Columbo episode.

What a great analysis! These techniques are useful for any mystery writer.

Sometimes the Killer would ask Columbo if he/she was a suspect and to disarm the killer, Columbo would insist that his Superiors required that he close up certain “loose ends”. He would make it seem like if it were up to him, he would just drop it. This was a clever technique because it let the killer know that he/she wasn’t dealing with an ordinary lazy detective who just wanted to wrap up the case and go home.The ‘loose ends” would absolutely have to be cleared up first, no matter how seemingly inconsequential.

Richard, you’ve clearly given this subject a lot of thought and I think you’ve done a great job of capturing most of the essential ingredients that go into creating an effective Columbo episode.

I have some contributions of my own to add.

My first additional ingredient concerns Columbo’s character. Columbo is essentially a “fish out of water” in whatever new setting he finds himself in. Although he initially knows little about each area he gets involved, he is always ready to dive right in and isn’t afraid to make mistakes. This is one of Columbo’s most endearing characteristics. Sometimes the new thing he learns in important to solving the case, sometimes it’s just played for laughs, and sometimes it’s both. Among the many new things that Columbo has had to learn about are the following: video recording, security systems, forensic bite mark evidence, magic and mental tricks, motion picture projection systems, subliminal messaging, wine, city hall bureaucracy and building codes, and modern art. Here’s an example of this important part of Columbo’s character from “Playback,” played for laughs, where Columbo visits a modern art gallery. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OlLqYBU8qsY

The second additional ingredient relates to the story presentation and what should not be shown in the episode. The classic Columbo story is not an exercise in visually demonstrating the step-by-step investigative procedures that a case requires. In contrast, the first part of a typical “Law and Order” episode does demonstrate those step-by-step procedures. The key difference here is that Columbo does indeed actually perform the necessary investigative steps, but the actual legwork and follow-up aren’t shown to the viewer. The extensive “legwork” typically takes place behind the scenes. But that is why Columbo is fully prepared when he conducts his interviews with the suspect. We only learn about all that extensive “legwork” during one of Columbo’s subsequent interviews. This is part of the cat-and-mouse interplay between Columbo and the murderer that we love to watch. Here’s an example from “Death Hits the Jackpot.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pZiv8vkxMac&t=5s

Thank you very much for this excellent contribution.

once again you have snubbed “by dawns early light.” you have no credibility.

Col. Rumford gets considerable attention in “step 1”: his sympathetic motive, his admiration for Columbo, and how something deeply rooted in his character — in Rumford’s case, his inability to overlook evidence of a breach of discipline, i.e., the fermenting of cider — proved to be his undoing. If only he had ignored that cider …

I will give you a challenge dear Columbophile : write the same kind of review, using only new episodes as exemples …

Sorry i just sas its not a post from Columbophile … m’y mistake

Here’s my “dream team” of 90’s stars who would have made great Columbo villans:

Jeff Goldblum

Michael Douglas

DanieStern

Geena Davis

Sam Neil

Arnold

Bette Miller

Any other ideas?

Just thought of Kelsey Grammer.

+1 for Kelsey Grammar. He would be amazing!

Michael Douglas would have been perfect! And well, thank you for a very informative article, Mr. Weil. Just yesterday I was thinking “When will Columbophile let Rich Weil write another article?” – and here it is. The perfect timing!

Thanks for the great post Columbophile! It always bothered me that the “new” Columbos” seemed to lose sight of step 1. With the exceptions of Mr Shatner, Ms. Dunaway and Mr. McGoohan. Perhaps in the 90’s it was a bit harder to to sign the big name stars.

Great article! I’ve had a few ideas myself about writing a Columbo episode, including a corrupt, smarmy lawyer who uses Columbo’s “just one last question” tactic to win her cases in court only to get her comeuppance when she crosses swords with the man himself.

Agree it is best when we can empathise with the murderer’s motive and when the murderer has a certain charm ( Nora Chandler and Ken Franklin are about perfect ) but not so sympathetic, like Abigail Mitchell, that we are slightly disappointed when Columbo doesn’t let them off the hook!

I would be very excited to read that story if you ever write it.

I have written four Columbo stories and am now working on a fifth. It is true what this article says, Columbo stories are extremely difficult to write.

Phenomenal article as always, thanks so much.

To this day I can’t understand why in “The Conspirators”, the murderer shows up in the hotel room where he killed the victim.

Makes no sense why he’d go to the room in the hotel where he killed a supposed stranger.