I’m not one to needlessly stoke controversy, but I’m breaking some new ground today by including an article that could be described as the yin to my Columbo-loving yang.

That’s not to say that the following article ‘Columbo’s Biggest Mystery’ is a diatribe against all we love about the good Lieutenant. Not at all. But it is an excellent balancing point that goes against the popular viewpoint held by fans in suggesting that Columbo, the show, wasn’t nearly as good as Columbo the character.

I came across this essay, which was originally published on medium.com website in January, via social media. While there are aspects of it I oppose (sometimes strongly), author Michael Zuzel backs up his arguments strongly and you may find there’s more to agree with here than you’d expect. After reading it, I knew it deserved to be brought to the attention of fellow fans who really enjoy a good debate about the merits of all things Columbo. I was delighted that Michael was happy to have his article reproduced here.

This is a lengthy piece (the single-longest article on the blog to date), so is best enjoyed with a relaxing coffee, an open mind and without those rose-tinted specs. Now it’s over to Michael…

If you were alive and conscious during the 1970s, you knew Columbo.

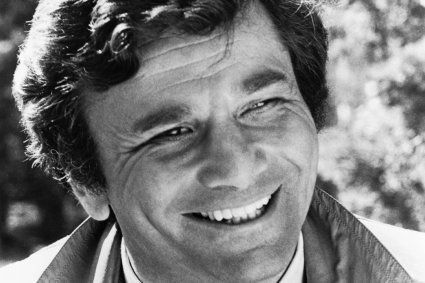

The often unkempt but endlessly resourceful Los Angeles police lieutenant, portrayed in the eponymous television series by the late Peter Falk, was a fixture of American culture during the period—as persistent and pervasive as the detective himself as he investigated yet another high-society murder. Even if you didn’t watch Columbo, you knew who he was, if only from all the magazine covers, the impressions by late-night TV comics, and the office water-cooler talk the morning after each episode aired.

In fact, Columbo’s reign extended far beyond that decade and on into the ’80s, the ’90s, and right up until 2003. Over the course of 35 years, 69 episodes, and countless cheap cigars, Columbo bird-dogged every clue and cracked every case, outwitting even the most clever and methodical killers. His signature attributes—among them a shabby raincoat, a bumbling persona, and a wonky gaze (thanks to Falk’s glass eye)—became imbedded into the pop vernacular, as iconic as Farrah’s flip and Travolta’s white suit.

As Tony Brownfield wrote in September 2021, the 50th anniversary of Columbo’s series debut:

“Audiences loved Columbo because he was unique. He was never slick or sharply dressed. He didn’t punch his way to the bottom of a mystery like Mike Hammer or rely on science like a Gil Grissom. He was, however, the smartest guy in any room, a fact that he underplayed with his disheveled appearance and chatty manner. By keeping the bad guys (who were often upper-class snobs) distracted, he was able to take his time and figure out what really happened. In the end, Columbo was just a slightly amplified version of a regular guy, and the viewers loved him for it.“

I was among those who loved him. I was a junior-high student during Columbo’s initial run, and my friend Rob and I loved to talk about “Cuh-bumble,” as we called him, and how he always managed to stick it to the hoity-toitys who thought they could get away with murder.

Binge those 69 episodes today, however, and a deflating realization sets in: Columbo isn’t as good as we remember it.

I hadn’t seen the show since its 1970s run, and though my memory of plots and characters was dim, I still held great affection for the series. Inspired by Alexis Gunderson’s heart-warming column about watching old Columbo episodes with her dad, I suggested to my wife that we spend a couple of our pandemic lockdown evenings each week with the lieutenant, retracing his journey from first episode to last.

When we were done, we’d come to two main conclusions. Yes, Columbo, the character, was superb. But Columbo, the show, was mostly mediocre. And at times atrocious.

I say this knowing that even today, fans of the series are many and ardent. Numerous books, blogs, podcasts, and videos are devoted to celebrating and analyzing the series. Half a century after Columbo’s debut, it remains a phenomenon, at least to the community of enthusiasts.

But I have a feeling that fondness for Columbo, not among disciples but audiences in general, stems mainly from memories of the detective’s many amusing eccentricities—his crappy old Peugeot, his fascination with shoes, his never-seen wife—and especially the way his awkward, tactless personality concealed his genius while offending the sensibilities of the haughty elites who were usually his prime suspects.

The stories that Falk’s character inhabited, by contrast, rarely rose to the same level of inventiveness, much less excellence. Hobbled by lackluster writing, network pressures and, unfortunately, Falk’s own imperiousness, Columbo seems today like one of its era’s lesser television programs.

And one of its great missed opportunities.

To understand how short of its potential Columbo fell, it helps to recognize how far it had to travel to arrive in the first place.

The character initially appeared, in primordial form and bearing the name “Fisher,” in print: a short story titled “Dear Corpus Delecti” by Richard Levinson and William Link, published in the April 1960 issue of Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. The tale (originally called “May I Come In”) involved a psychiatrist who kills his wife and uses his lover, disguised as the wife, as his alibi.

The young writing team soon reworked their story into an hour-long television drama, retitled “Enough Rope,” that was performed live on July 31, 1960 as an instalment of NBC’s The Chevy Mystery Show. The cigar-smoking detective was played by Bert Freed. He’d been renamed “Columbo.”

A third incarnation of the story, with a yet another new title, emerged when Levinson and Link turned the teleplay into a stage play. Prescription: Murder starred Thomas Mitchell (It’s a Wonderful Life) as Columbo along with Joseph Cotten (The Third Man) as the psychiatrist and Agnes Moorehead as his wife. The play opened in San Francisco in early 1962 and worked its way across the country with the goal of landing on Broadway by summer.

The arrival never happened. The road show’s lukewarm reviews turned ice cold after Mitchell dropped out due to illness and was replaced by a less charismatic understudy. The production shut down—but not before giving Columbo his most oft-repeated catch phrase.

As Mark Dawidziak revealed in his 1988 book, The Columbo Phile: A Casebook, Levinson and Link worked hard to stretch a 60-minute TV episode into a full-length stage production, and at one point in the rewriting process realized they had the detective exit the suspect’s apartment a few lines of interrogation too soon. Rather than retype the scene (a major chore in the days before word processing), the writers simply had Columbo turn around in the doorway and say, “Oh, just one more thing …”

With the play’s demise, the quote and the character might have dead-ended right there. But television provided yet another opportunity. In 1966, NBC announced plans for a series of two-hour made-for-TV movies, some of which, the network hoped, could then be developed as series. Levinson and Link overhauled Prescription: Murder yet again and pitched it.

NBC bought it. Columbo was back. And Peter Falk landed the role that would make him a star.

The Columbo who appears in the television version of Prescription: Murder, which aired in early 1968, is barely recognizable to fans of the later series.

Yes, he has the signature raincoat and the cigar. But he is young and sharp; his hair is trimmed and combed, and his approach to interrogation only hints at the unmannered distractedness that would later become his trademarks (and his grilling of the psychiatrist’s lover is conventional tough-cop cliché, not at all how the later Columbo would have handled it).

Regardless, viewers—25 million of them, one of the biggest audiences for a made-for-TV-movie up to that time—saw something they liked. NBC wanted Columbo to become a weekly series, but Falk, who was more intent on a career in movies, declined such a major commitment of his time and energies to the small screen.

It took another three years, but finally there was a compromise: Columbo would be part of a rotating weekly “wheel” of detective shows, alternating with McCloud and McMillan & Wife. Instead of 22 one-hour episodes a year, Columbo would appear just six to eight times a season in episodes of 90 minutes to two hours.

And so it went, beginning with a second pilot episode (Ransom for a Dead Man), which aired in March 1971, and extending over the next seven years—44 installments of what most fans consider “classic” Columbo. Among them are, without question (and in no particular order), some very good TV shows:

- Murder by the Book (1971), starring Jack Cassidy, directed by a young Steven Spielberg and written by an even younger Steven Bochco—and if you think those two collaborating on a Columbo episode would yield magic, you’d be correct.

- Suitable for Framing (1971), starring Ross Martin and featuring the detective’s greatest gotcha of the entire series—one I won’t divulge, because describing it to anyone who hasn’t seen it would not do it justice. (But you can watch the full episode here.)

- Negative Reaction (1974), starring Dick Van Dyke in a rare bad-guy role and a final shot that is one of the most fiercely debated of the entire series among fans.

- Try & Catch Me (1977), starring Ruth Gordon as the sweetest little mystery-writer-turned-murderer you’ll ever meet, whose victim gotchas her from the grave.

- Any Old Port in a Storm (1973), starring Donald Pleasence as a snooty winemaker deliciously hoisted on his own rare-vintage petard.

- A Deadly State of Mind (1975), starring George Hamilton and Lesley Ann Warren, with yet another great gotcha and a murder that exemplifies the hypnosis paranoia of the era.

- Forgotten Lady (1975), starring Janet Leigh, including a tragic twist ending unlike any other in the Columbo canon.

- A Friend in Deed (1974), directed by Ben Gazzara and starring Richard Kiley in a tale of police corruption that’s uncharacteristically dark for the series but still recognizably Columbo.

- A Stitch in Crime (1973), starring Leonard Nimoy as perhaps Columbo’s most ruthless and brilliant foe—Spock as a psychopath.

Yet even during these early years, before Columbo really lost its way, the stinkers outnumbered the winners. Episodes were constantly undercut by huge plot holes, poor pacing, wooden acting, and endings in which the suspects simply crumbled when confronted with the flimsiest of evidence. Even some of the better instalments suffered. Among the episodes to avoid entirely:

- Dagger of the Mind (1972), starring Richard Basehart and Honor Blackman, in which Columbo goes to London, does some tourist stuff, matches wits with Scotland Yard, and proves himself a nitwit.

- Short Fuse (1972), with an ending on the Palm Springs aerial tramway that appears to have been hurriedly ad-libbed in hopes of wrapping up the shoot before the car reached the top; the episode’s very title has become a punchline due to Roddy McDowall’s ultra-tight pants.

- A Matter of Honor (1976), starring Ricardo Montalbán, a ludicrous tale about bullfighting in Mexico, rendered basically unwatchable thanks to a barrage of offensive, racist stereotypes.

- Mind Over Mayhem (1974), starring José Ferrer in a story where the supposedly cutting-edge technology looked like it came straight out of the 1950s—because it did, in the form of Robby the Robot, who’d made his screen debut almost 20 years earlier.

- Last Salute to the Commodore (1976), starring Robert Vaughn and directed by Patrick McGoohan (more on this gentleman later), an episode so vile in so many ways it practically defies description—although Britain’s The Guardian, in an article titled “When good TV goes bad” summed it up in just two words: “truly berserk.”

These episodes are a special brand of awful, but they’re not actually atypical of the show. Australia-based super-fan The Columbophile has set out to analyze and review in detail every episode of the series; the site ranks just 16 episodes from the ’70s as truly A-list material.

I think that’s generous. For what it’s worth, IMDB.com’s crowd-sourced ratings don’t place even a single Columbo episode of the era in the “great” category, with almost half earning a “regular” or fair rating at best. Hardly what most people would consider a TV classic.

Even so, it’s hard to argue with the widely held view among Columbo cognoscenti that the 1970s episodes far outshine those produced during the show’s revival: 24 episodes that ran from 1989 to 2003.

The show had vanished after the 1977–78 season, not because it was formally canceled but because new management at NBC was determined to rally the network out of its last-place status. The plan centered on producing programming with greater appeal for younger, hipper audiences. It did not include Columbo.

So the show simply didn’t come back in the fall of 1978. Falk’s insistence on renegotiating his contract on a year-by-year basis made it easy for the network to just walk away. Nonetheless, the actor, who had spent years complaining that he was too closely tied to the Columbo character and insisting that he’d rather make films, almost immediately began trying to persuade NBC to bring the detective back to the small screen. Repeatedly. With no success.

A decade later, though, it finally happened—on another network. By 1988, enough time had passed for Columbo to become a nostalgia property; ABC wanted to use the character’s familiarity to attract viewers to new shows, starring Louis Gossett Jr. and Burt Reynolds, that would comprise a new mystery-movie “wheel.” (After 1990 and several iterations, the wheel was jettisoned, and Columbo continued as a series of stand-alone movie specials for the next dozen years.)

The producers promised that the new Columbo would be the same as the old, with perhaps a few concessions to late-’80s and ’90s sensibilities—like not having the detective light up his cigar so often.

The later incarnation does offer more contemporary production values, which perhaps make these episodes more superficially appealing to 21st century viewers. Beneath the surface sheen, though, Columbo Redux is mostly awful. For example:

- Murder in Malibu (1990), starring Andrew Stevens and Brenda Vaccaro, both overacting as though they never wanted to work in Hollywood again, and featuring several “oh-ick-I-can’t-unsee-that” scenes of Columbo caressing women’s underwear.

- No Time to Die (1992), based on a very-un-Columbo-like novel by Ed McBain; it seemed at the time like a clumsy attempt to move in on the hard-edged crime procedural territory of Law & Order. Jerry Orbach would have nothing to worry about.

- Butterfly in Shades of Grey (1994), in which William Shatner’s usual histrionics are actually upstaged by his ever-changing fake mustache, an uncanny spectacle of migration and changing colors that inspired a brutal scene-by-scene analysis.

- Undercover (1994), another episode based on an Ed McBain novel, with Columbo going incognito for no reason except to prove, apparently, that the bumbling personality we’ve come to love over the decades was all a put-on.

- It’s All in the Game (1993), Falk’s only teleplay credit, another thin story with Columbo acting out of character, an exercise that seemed designed primarily to give the actor a chance to kiss Faye Dunaway. But the chemistry between them is, shall we say, inert.

- Murder with Too Many Notes (2001), directed by Patrick McGoohan (again, more on him later), with so many false starts and such a nonsensical conclusion, it’s as though Columbo simply announces the case is solved and the murderer confesses. Roll credits.

I could go on. At least half a dozen other episodes in the second incarnation could arguably rank among the worst. Not one matches, much less surpasses, the Columbo of the 1970s—which should not have been an impossibly high bar.

Indeed, the whole revival effort has a slapdash feel. Gone for the most part are the big-name guest stars of the earlier era, when Janet Leigh, Vincent Price, John Cassavetes, Ray Milland, Richard Basehart, Anne Baxter, Vera Miles, Louis Jourdan, and even Johnny Cash all made appearances. Back then, the opportunity to play a murderer was clearly a draw for top-drawer Hollywood talents who wouldn’t otherwise deign to appear on TV.

In the new Columbo, by contrast, we are served up Andrew Stevens, George Wendt, Rip Torn, Robert Foxworth—fine actors, but largely television people and not exactly A-list at that. And that’s just the start of the problems with the comeback show. Plots are rehashed; locations are reused; Falk’s acting grows increasingly cartoonish. It is painful to watch.

The end came in January 2003, with an instalment titled Columbo Likes the Nightlife. Set in a rave nightclub, with settings and characters that would have been at home in an episode of CSI, it was actually one of the more successful attempts to transplant the detective into a contemporary milieu, more than four decades after his first television appearance.

But Nightlife bombed in the ratings. That was enough for ABC. Falk’s per-episode salary had skyrocketed over the years, and the network decided that producing such an expensive show, even on an occasional “special television event” basis, was no longer viable. The detective had solved his last murder.

Columbo’s second demise proceeded much like its first, with no formal cancellation announcement and with Falk refusing to let the character rest in peace. The actor spent the next several years pitching the idea of a final farewell episode, one he’d written himself. When ABC wouldn’t buy it, he approached other networks, including cable channels and even overseas production companies. All declined.

When Peter Falk passed away on June 23, 2011, at age 83, television lost a singular, indelible character—one who, sadly, is forced by DVDs and streaming services to shuffle around for all time through dozens of unexceptional stories.

Watching Columbo today demands that you wash down your popcorn with gallons of rationalization. Often it’s just too much to swallow.

Set aside, if you can, the static camera work, the ponderous scene-setting, the sexual and racial stereotypes—all to some extent typical of the times in which the show was produced. Network television, especially during the 1970s, was subject to the limitations of budgets, the sensitivities of advertisers, and the capriciousness of network executives. Most shows achieved excellence only occasionally and often by accident.

What’s harder to overlook is Columbo’s lame storytelling. Plotlines don’t so much race along as sag; dialogue is less snappy than perfunctory. Suspects confess readily—more often, it seems, from weariness than from any open-and-shut evidence against them. Lengthy sequences, often with no relevance to the mystery at hand, achieve little more than to show us the detective in yet another amusing (or not very amusing) predicament.

Yes, many scenes and sometimes entire episodes shine with the craft and care that clearly went into making them. But many, many more are simply boring and awkward.

And for that, we cannot blame the times. After all, the 1970s were the years that gave TV viewers All in the Family and M*A*S*H; the 1980s, Hill Street Blues (created by frequent Columbo writer Steven Bochco) and Moonlighting; the 1990s, The Sopranos, The West Wing, and ER. Admittedly, all of these series had their lackluster moments. But taken as a whole, all are examples of outstanding television of their respective decades, and all hold up relatively well today—in ways that Columbo simply does not.

So what happened? How could such a promising character, such an auspicious premise, end up in failure time and again? Especially a show that had the luxury of producing only a handful of episodes each season?

Having watched all 69 episodes in the order they first aired, and after reading Dawidziak’s The Columbo Phile as well as David Koenig’s superb Shooting Columbo: The Lives and Deaths of TV’s Rumpled Detective (an episode-by-episode history of the show’s production, published in 2021), I have a possible answer. Actually, three of them:

- First, Columbo was built upon a brilliant but unconventional format that few writers could successfully navigate.

- Second, the series was diminished by the tendency to make the detective more of a caricature with each successive episode and by pressure to make those episodes longer than their stories could support.

- And third, Columbo’s very existence rested entirely on one man—Peter Falk—who immediately recognized the tremendous leverage he possessed over the whole enterprise but whose interests did not always align with the show’s.

The format challenge

From the very start, with the proto-Columbo played by Bert Freed in The Chevy Mystery Show, the series took an unusual approach to the crime genre.

Rather than an Agatha Christie-style “whodunit,” in which the plot culminates with the detective revealing the perpetrator’s identity to the audience, Columbo episodes were almost always an “inverted mystery” or “howcatchem,” in which the killer’s guilt is known to viewers from the outset and the story revolves around the process by which the detective assembles the evidence to prove it.

No car chases, no gun fights, no bare-bulb-in-a-blank-room interrogations. Just lots of genial but probing conversations between Columbo and the murderer, culminating in a “gotcha” moment (or, as the show’s producers dubbed it, the “pop”) when a key piece of evidence, or the cumulative weight of all the clues, prompts the perp to confess.

Obviously it’s more challenging to create dramatic tension when the audience knows the answer before the detective does. The inverted mystery format had been around for decades in literature and was used most famously in Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder. But the unconventional structure apparently befuddled many of Columbo’s writers, who didn’t seem to recognize that it was the dynamic between detective and suspect, far more than the amassing of clues, that fueled good drama.

Columbo’s creators, Levinson and Link, clearly understood the principle; the lieutenant’s conversation with the psychiatrist in his office in the pilot episode, Prescription: Murder, is a veritable master class in creating excitement and anticipation through simple dialogue. The sequence, which lasts a full 12 minutes but never lags for a second, sees Columbo humbling himself while flattering the suspect (played with perfect arrogance by Gene Barry) and finally wheedling the psychiatrist into describing how the murder was committed—hypothetically, of course.

But Levinson and Link left the show after the first year (they went on to help create Murder, She Wrote) and later expressed dismay at the poor quality of the writing in subsequent seasons. Indeed, Koenig’s book, based on interviews and documents provided by people involved in making the show, reveals a constant struggle by Columbo’s producers to secure inventive stories and high-quality scripts. A struggle that often ended in failure.

Dawidziak reached the same conclusion. In The Columbo Phile, he describes how, prior to the first season, Levinson and Link screened Ransom for a Dead Man for about 60 Hollywood writers; afterward, only two expressed interest in working for the show. “The Columbo formula was intimidating enough to scare off the vast majority of Hollywood writers,” he wrote. “As a result, there was no talent pool to draw on.”

It’s not surprising, then, to see similar plot points recycled over and over in Columbo. In at least two episodes (A Friend in Deed and Columbo Goes to College), the detective trips up the murderers by purposely letting slip information about a supposed suspect who doesn’t exist. In two others (Suitable for Framing and It’s All in the Game), the killer tries to mislead investigators about the time of death by covering the victim with an electric blanket. In at least three episodes (Publish or Perish, The Most Crucial Game, and Identity Crisis), a tape recording is the key piece of evidence. And I lost track of the number of times a perp pointedly asked someone for the time as a way to establish an alibi.

One egregious example of recycling proves just how low the show could go: Uneasy Lies the Crown, which aired in April 1990.

Actually, the episode, or one almost identical to it, aired first in March 1977 on the series McMillan & Wife. Bochco had written the script in 1972 for Columbo, but Falk had rejected it; according to Dawidziak, Falk’s mother, Madeline, heard a description of the episode and declared that no one would believe that a dentist could be a murderer. Apparently that’s all it took for Falk to axe the idea at the time.

So Bochco had revamped the script and sold it to McMillan. Then, 13 years later, during the second season of the Columbo revival, Falk and the show’s producers found themselves so desperate for stories that they dug up Bochco’s script, turned Rock Hudson’s character back into the one played by Falk, and aired the result: a remake of a reject.

“Uneasy Lies the Crown doesn’t even try to hide its connections to the past by changing character names,” The Columbophile writes. “It simply boldly retells the same story with the same characters, making only slight cosmetic changes, padding out scenes to lengthen the running time, and adding in the tedious sub-plot about laundry bluing to make the gotcha much more confusing than in the original.”

The Crown debacle is just an extreme example of the hasty, inept scripting that bedeviled the show throughout both of its runs. To be consistently successful, the series needed a clear vision not only of its central character but also of the kind of tales it wanted to tell, and how. Too often, though, good stories were an afterthought.

The formula crutch

In his seminal 1973 book The World of Star Trek, David Gerrold contemplated the ways in which a network television show can experience deterioration of its format into mere formula by what he terms a creative “hardening of the arteries.” Watch all 69 Columbo episodes in order, and you can practically see the sclerosis forming before your eyes.

Throughout the series, huge quantities of screen time are devoted to having Columbo do nothing related to the case at hand but instead simply find himself in an unfamiliar, uncomfortable, or supposedly humorous situation:

- In Dagger of the Mind (1972), Columbo spends a full two minutes frantically taking photographs of the changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace.

- In Candidate for Crime (1973), Columbo visits an auto-repair shop, gets pulled over by a traffic cop, and listens to his dentist talk about the stereotyping of Italians in the media.

- In A Friend in Deed (1974), Columbo’s car won’t start, and he spends several eternities attempting to open the hood and trying to flag down passing motorists.

- In An Exercise in Fatality (1974), Columbo waits almost seven minutes for a computer printout—an exercise in fatality for viewers, for sure.

- In Make Me a Perfect Murder (1978), Columbo sits down at a broadcast control board, punches random buttons, and stares at pretty patterns on the screen for what seems like forever.

- In Columbo and the Murder of a Rock Star (1991), the detective visits a bar that features a mermaid on wires hanging behind a fish tank; the conclusion of the scene, centered on a toothless drunk staring agog at Columbo and the sea nymph, ranks as “15 of the worst TV seconds I’ve ever seen and it enrages me every time,” writes The Coumbophile.

- In Murder with Too Many Notes (1995), Columbo helps his drunken suspect make his way home, a seven-minute journey replete with stock classical music, pointless high jinx, and not a single interesting moment—the very opposite of the tense, revealing Columbo-vs-killer conversation in Prescription: Murder.

These sequences and many others were ponderous and superfluous when they aired; viewed today, they just seem amateurish and stupid. Many were inserted near the end of each episode’s production work at the insistence of the networks, which could pull down more revenue selling Columbo as a two-hour show than as one lasting only an hour and a half. The padding is obvious, and it kills whatever good storytelling surrounds it.

“Columbo was crisp at 90 minutes,” Bochco told Dawidziak. “At two hours, it was a bit indulgent and inflated.” Some fans have gone so far as to create their own versions of overly long episodes, editing them down to reduce the bloat.

But the networks can’t be blamed for another major contributor to Columbo’s slump: the way the detective degenerates from quirky character to crass cartoon over the course of the series.

In the latter half of the classic run, and especially during the revival years, our detective’s peculiarities become more numerous, his mannerisms more exaggerated. Falk’s speaking voice becomes higher and more shrill; he flails his arms like a windmill in a cyclone. The detective and the show he inhabits become more reliant on gimmicky theatrics and thus more predictably ludicrous.

As Koenig writes, “Falk, in trying to stretch the character, was unwittingly turning his portrayal into a broad caricature, like a comic doing an impression of Columbo.”

The fault lies not just with Falk but also with Columbo’s writers and producers, who clearly felt the need to take aspects of the show that had generated buzz and make them even more outlandish. If viewers and critics were saying, “Did you see the crazy thing Columbo did last night?” then the message to the show was, “OK, so next time we’ve got to make him do something even more over-the-top.”

Thus, we see the detective fondling women’s underwear (and saying “panties” again and again) in Murder in Malibu. We see him issue an all-points bulletin for a cat (“That cat could be the only witness to this terrible crime! I want that cat!”) in A Trace of Murder. We see him babbling imbecilic baby talk to a potted plant in Columbo Goes to the Guillotine. We see him practically drooling while walking among the swim-suited models gathered poolside—and then, predictably, getting soaked—in Columbo Cries Wolf.

“Falk had looked forward to playing Columbo in his old age, when the character’s forgetfulness and other eccentricities might seem normal,” Koenig wrote. “Yet, his performance had the opposite effect. Columbo started to come across as borderline senile.”

And when the writers didn’t have a great pop at the end, they settled for a gag, even if it was entirely inappropriate in the context of the story. All four episodes from Columbo’s first revival year, 1989, exhibited a grotesque overreliance on cute, nonsensical contrivances to cap off scripts or just extend their running time:

- In Columbo Goes to the Guillotine, the detective arrests the suspect in a magic workshop by shooting him with a fake gun, a “bang” flag bursting from the barrel. This from a detective famous for never carrying a firearm.

- In Murder, Smoke and Shadows, Columbo pronounces the case solved by suddenly and inexplicably transforming into a circus ringmaster (which, aside from the jarring fantasy element, doesn’t even qualify as poetic in an episode that’s about movie making, not circuses).

- In Grand Deceptions, the final shot pans across a miniature Civil War battlefield diorama, landing on a figurine of Columbo himself (which could not possibly exist given the events of the episode).

- In Sex and the Married Detective, we get almost certainly the most moronic, awkward, and pointless Columbo scene of all time, in which we learn the lieutenant can play the tuba—and somehow has the power to make fountains dance in sync with his honking.

These were cheap punchlines, not plot developments—a retreat to unimaginative formula when the demands of the format simply exceeded the writers’ imaginations. As Gerrold put it:

“Formula occurs when format starts to repeat itself. Formula occurs when format does not challenge writers—or when writers are giving less than their best. Formula occurs when a show becomes creatively bankrupt. Flashy devices can conceal the lack for a while, but ultimately the lack of any real meat in the story will leave the viewers hungry and unsatisfied.”

Unsatisfying. Many episodes of Columbo were, and are, exactly that.

The Falk Factor

Just as there is no way to fully separate the fictional character called Columbo from the performer who portrayed him, it is impossible to examine the shortcomings of the show called Columbo without acknowledging the major role Peter Falk played in those failures.

As co-creator Richard Levinson put it, Columbo “was one of those once-in-a-lifetime weddings of character and actor.” Falk recognized this almost from the start. Even before the regular series premiered in the fall of 1971, the actor began trying to assert creative control over the show: arguing with the writers over plots and characters, demanding his own representative on the production staff, and having “terrible blowouts,” as Bochco put it, with Levinson and Link.

Ultimately, Koenig writes, Falk became so disruptive that Universal barred him from the production lot except when he had scenes to shoot—the first skirmish in three-way war between studio, network, and star that persisted over the next three-plus decades.

Some would say those fights were justified. Even Levinson, with whom Falk clashed so often, credits Falk for being “the conscience of the show.” And though the actor’s beef was often about his salary, just as often the issue was creative control of Columbo. Few would blame the actor for using the power of his unique position to improve the series.

Trouble was, he often ended up doing the opposite. He was neither a skilled writer nor an experienced director, yet he was constantly at loggerheads with the creative staff over how shows should be plotted and filmed. As an actor he was notorious as an on-set perfectionist but an indecisive one—demanding take after expensive take, sometimes lasting late into the night and early morning, yet seemingly never being satisfied.

Falk’s sway over every aspect of the show grew with each passing season, and soon he was hand-picking scripts, actors, directors, and producers. Some of those choices, unfortunately, were directly responsible for many of the worst episodes of Columbo.

Two appalling examples arose from a single, impulsive decision by Falk—“one of the most wrongheaded moves in the celebrated history of Columbo,” as Dawidziak puts it—to buy the rights to a pair of 87th Precinct novels by Ed McBain and adapt them for the series. Although crime stories, the novels were conventional procedurals and, as the producers quickly discovered, a poor fit both for the show’s format and for Columbo’s character.

Painted into a corner, the writers of the resulting episodes—No Time to Die and Undercover—simply scrapped the Columbo format (the former doesn’t even include a murder) as well as the Columbo character (the latter leaves him virtually unrecognizable). No inverted mysteries; no real pops at the end; and no Columbo doing what he does best: observing, chatting, connecting the dots, and closing in. As examples of the procedural genre, they’re forgettable; as Columbo episodes, they’re pure blight.

Significantly, though, there was one person who thought using the McBain novels to turn the series upside down was a terrific idea (according to Koenig): Patrick McGoohan. That small fact is revealing. I submit that it was Falk’s long collaboration with McGoohan, during both runs of the series, that inflicted the most damage on the Columbo canon.

The Irish-American actor was not a big star in the United States (although his allegorical 1967 British series, The Prisoner, has since become a cult favorite), and Falk wasn’t really familiar with his work. The show’s producers persuaded him that McGoohan would be perfect to play a military-school commander turned murderer in the fourth-season episode By Dawn’s Early Light (1974).

McGoohan’s performance in the episode is uncharacteristically understated—the last time, throughout his many stints as actor, writer, and director on Columbo, that he exercised any restraint at all.

Unfortunately for the show, McGoohan and Falk hit it off; “Falk adored McGoohan’s unpredictability,” writes Koenig. The subsequent trail of disasters includes:

- Identity Crisis (1975), with McGoohan starring and directing, an unnecessarily complex episode involving spies, marred by an ending that fizzles instead of pops and a groaner of a scene in which Columbo is rendered nearly catatonic by the mere sight of a belly dancer. Per Koenig, McGoohan was reportedly drinking heavily at the time and incurred substantial overtime costs during production.

- Last Salute to the Commodore (1976), perhaps the worst Columbo ever, directed (and heavily rewritten) by McGoohan, who seemed to think it would be hilarious for Falk to act as if his character was constantly stoned. Entire scenes were filmed with little or no rehearsal, and they show it; the episode’s resolution looks like it was staged by a community improv troupe on an off night.

- Agenda for Murder (1989), another dual acting-and-directing effort by McGoohan, a decent political thriller undermined by a pointless subplot involving dry cleaning. According to Koenig, McGoohan’s arbitrary decision-making and arrogant manner managed to alienate just about everyone who worked on the episode—except his buddy Falk.

- Ashes to Ashes (1998), overall a so-so episode, again directed by and starring McGoohan, this one centers on an undertaker to the stars; it’s memorable mainly for the medley of awful death-themed song parodies performed at a funeral directors’ convention. It lasts only 90 seconds but takes years off a viewer’s life.

- Murder with Too Many Notes (2001), a script McGoohan had heavily rewritten and directed almost three years earlier but which was relegated by the network to the shelf—where it should have stayed, thanks to its previously noted, very unfunny drunken driving sequence and an ending so batshit surreal, it would have been more at home in The Prisoner.

McGoohan’s influence on Columbo extended far beyond the six episodes in which he is listed in the credits; from the mid-1970s onward, Falk consulted with him on casting and directing decisions, enlisted him to polish scripts, and used him as a frequent sounding board. Many of the show’s fans consider the collaboration between these two men to be among the most fruitful of the entire series, but for me McGoohan’s impact was, on balance, hugely detrimental.

“Patrick McGoohan was simply bad for Columbo.”

McGoohan (who died in 2009) was a political libertarian and a television anarchist; his natural inclination was to defy authority, question norms, and gum up the works as much as possible. The Prisoner (which my wife and I also rewatched from start to finish during the pandemic) was less a sci-fi/spy thriller than a personal manifesto for McGoohan. His philosophy—which included a disdain for “low-mentality viewers” and a belief that writers of commercial television shows were “prisoners of conditioning”—was palpable in the many decisions he made on Columbo.

Unfortunately, that contrarian philosophy did not mesh at all with an understated police procedural whose following was built on a well-established central player possessing a set of consistent eccentricities. Koenig writes that McGoohan “seemed most intent on stretching the Columbo character in new directions. He didn’t believe that Columbo was really humble or polite. To him, that was an act, which the detective could turn on or off as the situation merited.”

Trouble was, most Columbo fans most definitely didn’t think it was an act; the appeal of the character stemmed from the idea that a genuine bumbler could also be a brilliant puzzle-solver—the “smartest guy in any room,” as Brownfield put it. To audiences, that’s what made Columbo so fascinating—and so funny. (Doubtless McGoohan would dismiss them as “low-mentality viewers.”)

Imagine a Columbo with no Last Salute to the Commodore, no Murder with Too Many Notes, no Ed McBain episodes—what a relief! Even if all of McGoohan’s other contributions were erased as well, the result would still be a net improvement for the series overall.

McGoohan was simply bad for Columbo. Unfortunately, writes Koenig, “Falk trusted him implicitly.” That trust perhaps made for a wonderful friendship. But it also resulted in marginal, and often downright awful, television.

Unlike Dawidziak, Koenig, The Columbophile and many, many others, I’m no expert on Columbo. But I am, despite everything I’ve just written, a fan of the show.

That’s no contradiction. As The Columbophile put it: “No man, woman or child loves Columbo more than I. But love needn’t be blind and I don’t believe in the fawning viewpoint that the show was free from faults. Far from it. And some of its worst moments were very bad indeed.“

For my part, I believe that Link, Levinson, and Falk created the greatest television detective of all time and one of the most consequential TV characters in any genre. The fact that books are still being published about the show, an online fandom community is thriving, and people continue to be inspired to revisit a character invented more than six decades ago is powerful evidence that Columbo is truly a classic fictional figure.

But the show that carried his name seldom embraced the brilliance embedded in its DNA. We remember Columbo as better than it was because that’s the show the character, and the audience, deserved. Sadly, the opportunity for that better show is lost: Falk is gone, Levinson and Link have both passed, and any attempt at a reboot would be foolish and doomed to fail.

I like to pretend that many of the detective’s greatest cases somehow never got filmed. In my mind, these are stories in which the crime seems unsolvable, the clues inscrutable. The plot moves briskly but not breathlessly; there are moments of whimsy but not a wasted second. The detective spars verbally with the suspect again and again, but the murderer remains coldly defiant.

I think: Is this, finally, a mystery that can’t be cracked? Maybe this is the one that ends with the killer going free? But in the final seconds, a forgetful fellow in a raincoat—after looking for his lost pencil, petting a dog named Dog, whistling “This Old Man”—drops the bomb. The biggest, most unexpected pop ever. The evidence, invisible just moments earlier, is now irrefutable, the proof apparent to all. And another rich, hubristic asshole is going to prison.

Oh, and there isn’t just one more thing. That’s the whole thing. Columbo’s biggest mystery. Unseen, but not unsolved.

— — — — — —

Michael Rene Zuzel (michaelzuzel.com) is a writer and musician in Southern Oregon. He is currently writing a pandemic-inspired cocktail guide (details at patreon.com/michaelzuzel).

This article was originally published on medium.com in January 2022.

Homepage thumbnail by Dawn Hudson.

There we have it gang, a lengthy summation of some of the series’ faults and foibles. To what extent do you agree with Michael’s arguments? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments section below – particularly with regard to his commentary about Patrick McGoohan’s influence on the show and the character. Sacrilegious or warranted? Let me know…

And as for the site update, I’ll be implementing that in the next week, so LOOK OUT for a (hopefully) new and improved visitor experience. Until then, farewell…

The biggest mystery in the Columboverse is the Lieutenant’s badge with his real photo. Never mind that the signature says “Frank Columbo” but why did they keep using it over and over when Levinson and Link didn’t want to reveal his first name? They obviously didn’t contact the prop dept. about fixing the problem. Then there’s it’s bizarre appearance in Blueprint for Murder. And Falk directed that episode! Clearly he he had one hell of a perverse sense of humor regarding his badge. What a cheeky fellow Frank Columbo was!

In defense of two of your choices for worst episode,

I would say this:

Dagger of the Mind is mostly enjoyable fluff, with Columbo

only along as a tourist, doing silly touristy things. True, the

villains’ dumbness, nor their reactions to the Gotcha, aren’t

really believable. But in no way does the episode offend me

like Mind Over Mayhem does.

Short Fuse had a good setup, and final Gotcha, but got

rushed into completion to squeeze in another episode.

You could leave out the middle part, but it’s not all bad.

I have yet to watch Last Salute to the Commodore again,

but I can hardly wait.

“Dagger of the Mind is mostly enjoyable fluff, with Columbo

only along as a tourist, doing silly touristy things. True, the

villains’ dumbness, nor their reactions to the Gotcha, aren’t

really believable. But in no way does the episode offend me

like Mind Over Mayhem does.” (from DOGMEETDOG)

I agree 100%. I like Dagger, in fact, while fully acknowledging its lack of heft and believability. I thought Basehart and Blackman and Hyde-White were all fun. 🙂

An interesting essay. I won’t say I disagree with Zuzel with respect to the bad episodes. When Columbo was bad, it was really bad. But I do disagree with his view that the good episodes are only slightly good. No. When Columbo was good, it wasn’t just good, it was extraordinarily good. Ultimately, I think what makes great cinema/television is how satisfied you feel at the denouement. And with Columbo, when he used his psychological warfare to destroy the arrogant, entitled perpetrators who seemed otherwise immune from justice, there was a level of moral and narrative satisfaction that few television shows have ever been able to equal.

Hi,

I’m looking for a Columbo episode in which the murderer leaves the hospital following his operation (appendicitis I think) in order to have an alibi. Could anyone help me? Thanks.

A Stitch in Crime (which is about dissolving sutures used in heart-valve surgery) is the only hospital episode I know, besides a brief dash to the hospital to learn that the victim has died in Prescription: Murder.

The episode Ghislaine’s description brings to mind is ‘Troubled Waters’ in which Robert Vaughan’s character, Danziger, slips out of the sick-bay of the cruise liner in order to do the dirty deed to his ex-lover Rosanna, played by the wonderfully named Poupée Bocar. He slips back into bed unnoticed leaving the vacationing Lt C. to unpick the mystery.

Oh, good thinking! 😎

I should’ve thought of that cruise-ship episode, which I always liked and have seen several times.

I must say that I agree with most of what Michael Zuzel has written. I have no knowledge of the behind-the-scenes shenanigans he refers to but they probably do have a bearing on why much of Columbo could have been ‘better’ (certainly it might have been different) as far as TV crime drama is concerned.

For this particular viewer Zuzel is somewhat missing the point. I enjoy the programme despite the shortcomings, sometimes even because of them. In its day the original series had charm and wit, it was never believable and I don’t think it was ever intended to be so. It was pretty harmless escapism unencumbered by the need to deliver a message (other than the very basic ‘crime doesn’t pay’). It was right in there with Starsky & Hutch, Vega$, The Rockford Files, and Banacek among others. The likes of Kojak, The Streets of San Francisco, Harry O, and Ironside were more likely intended as ‘serious’ drama with a message. They were all watchable and most of the shows I’ve mentioned here could do with TV reruns.

In 2022 Columbo is a huge slab of enjoyable nostalgia which I take in small doses so as not to spoil the pleasure. This blog and the analysis of each episode only add to the fun.

How bad can a show be, that has earned as much print as it has over the decades, just for the reason of being second-guessed?? There are only 3 factors involved in the show:

• Execution (the brilliance or not of acting and shaping the character).

• Purpose (what’s the episode trying to say)

• Setting (meaning placement, context, visibility, atmosphere)

Put those factors (meaning elements of consideration) up against similar shows of the day (its contemporaries, and all of them). And one of those elements (factors) is going to be missing. Which means their show isn’t worth that much over-thinking. It’s just a moment in time.

It is only because of the depth of Columbo in the first place, that we’re still talking about it today. Not that other shows don’t have their own rabid followers too. Just maybe not as intense.

Two things happened to Columbo along the way: (One) it got trapped by its own dangerous self-awareness (trying too hard). And (two) viewers expecting too much, and especially after-the-fact. While some viewers like to hang on a memory, that’s great! But in the day, in the moment of the experience, it’s only about entertainment. Sometimes it wins, and sometimes it loses. Which this article has spent much time on deciphering, why. I get it.

But at least celebrate Columbo’s intention. Craft and acting talent deserves at least that much! And by the way, Troubled Water wasn’t even mentioned. I like that its perfectly obvious and we can just sail along with the passengers and crew Like taking a vacation from over-thinking. And enjoying the characters on board!

To the authors of the article: thank you though, for your very thoughtful contribution to the conversation. Every writer through determined analysis and style of expression, gives away a little piece of his or her self. Meaning, the contributor is worth appreciation!

Only thing worse to view than Last Salute to the Commodore was this essay. Everything from the past is lamer than the present. No one is reading this blog on a Commodore 64, are they (yes, I did that on purpose)? Anyone still have a flip phone who isn’t known as the most boring person in their network of friends? C’mon…Hill St. Blues or Law & Order? Gilligan’s Island and Hazel or Seinfeld and Friends? P-51 Mustang or F-22 Raptor? Bette Davis or Jennifer Aniston? Ever look back at your high school yearbook, and think, “hmph, I always thought Biff McDoogle and Buffy Skankerton were better looking. And, what’s with the mullets???”

Late coming into this thread, but I think there are a lot of good observations here. One thing to add: we have been in a golden age of series television for some time now. The shows we watch now often have much higher standards, original concepts, first-rate showrunners & actors, etc. than the ones decades ago. They learned from the past shows that we love, such as Columbo, & build on them. So it’s not just nostalgia that causes disappointment when we re-watch old favorites – our standards have changed because we have such good TV to watch now.

It’s also worth pointing out that despite all that, Columbo is still generally extremely entertaining and satisfying to watch, even after all this time. I started watching during the pandemic like so many others, and even the worse ones are generally enjoyable. They’re (99% of the time) character studies of two enigmas: the person who seems to have everything and still commits murder, and the very likeable, very mysterious man who inevitably catches them. Like nothing else on TV. I also started watching “Murder, She Wrote” during the pandemic based on very fond memories, but I quickly stopped – every episode I tried seemed crammed with stereotypes and bad acting (Angela Lansbury always excepted), and barely held together compared with Columbo.

Point is: Columbo had plenty of problems in retrospect – much more obvious to us now – but it’s still a great character and a great watch.

I love an article like this even though I don’t agree with it. I think the one thing the author is not considering is television at that time. My first Columbo was Ransom For A Dead Man, I was all of 9 years old. No way was I old enough to understand the nuance or subtlety of the performances. Personally, I didn’t like Columbo, but if an episode was being broadcast, first run or rerun, it was on the living room TV. Columbo was part of my formative years. Now, I’m going to compare it to the rest of the NBC Mystery Movie slate. Even a kid like me, who really did not get what was going on, could see that Columbo was,by far, the highest quality show they had. It had better actors, better writing, more clever plots and, in the end, better directors. I loved the show Banacek. Now, when I watch it, I’m actually embarrassed that I once thought it was great. Same for McCloud, McMillan & Wife and any other spoke in the wheel. The same is true for any other police show from the 1970s. Columbo was on a different level. Were there clunkers? Oh Yeah! Nothings perfect. I won’t list, but I agree with the author on all Patrick McGoohan directed episodes and found it interesting he had so much influence. Still, I found this article thought provoking, the main thought being, it was written 45 years after the show ended its initial run. How many people would write an article like this about McCloud or McMillan?

Excellent points! Columbo was indeed on a whole different level from the rest of the entries in that Mystery Movie slot.

I think that only The Rockford Files (among similar series of the same time) approached Columbo in quality.

“How many people would write an article like this about McCloud or McMillan?” Indeed!

I imagine watching Columbo with this guy would be similar to watching Used Cars with my nephew, i.e. I’m watching to be entertained while he’s watching to be offended. I’ll be the first to admit that I find the boy genius and girl genius and geisha and Russian maid and Roddy McDowell’s pants and Falk’s portrayal during the reboot as gaggifying as the next guy, but I still enjoyed watching elite snobs slowly discovering their lack of eliteness as the rumpled detective reeled in his prey. Toss in an interesting murder and credible gotcha and I’m satisfied.

I tried watching Rockford Files the other day. I suppose if I’d taken notes I’d have had some clue as to what was going on. 27 charcters. I suppose one of them hired him for one thing or another. Maybe that’s why I like Columbo. I know the players and goal before the show even begins. Come to think of it, I seldom bothered watching the murders. I was in it for the chase.

I love The Rockford Files, but otherwise I agree with your post 100%!

Whoops! I should give it another try. I was in search of Gretchen and may have been distracted.

😄

I’ve got to expose one of the the elephants in my Columbo room…..Shera Danese. It’s nothing personal, but for me, episodes with her in them remind me of the Clint Eastwood movies that co-starred Sondra Locke. They’re not bad, per se…..but just….I dunno….nothing special. The 2 – early era Columbo eps with Danese (‘Fade into Murder’ and ‘Murder Under Glass’) and 4 later eps (‘Murder, A Self Portrait’, ‘Columbo, and the Murder of a Rock Star’, ‘Undercover’, and ‘A Trace of Murder’) were rather blasé. (in my unholy opinion only, of course)

I’ve never understood what Falk saw in Shera, either on or offscreen. (or Eastwood for Locke, for that matter)….there…..I’ve said it, and feel better and relieved to get it off my chest. Flame away…..

Back to the Zuzel article and the overall differences between the early and later Columbo eps, this topic reminds me of another favorite series of mine, The Andy Griffith Show. When the most pivotal character and funny man (Don Knotts) left after the fifth season for a movie career, variety shows, and voice-overs, etc., the series then switched from b&w to color film, and most die hard fans were not interested in the final 3 years of the colorized, Knott’s-less episodes. Griffith really lost his comedy mojo without his friend and co-star Barney Fife. (Knotts) In the colorized episodes, Griffith’s character (Andy Taylor) always seemed disgruntled and disinterested in the events of the fictional town of Mayberry. Lame scripts, production, and new bland character actors didn’t help much either. However, when the 249th and final show aired after 8 seasons, it was still #1 in the Nielsen ratings, which proves that the “arts” don’t always have to be performed well to be popular.

I also concur with the Twilight Zone discussion above. The 4th season of T.Z. were one hour eps compared to half hour format with seasons 1-3 and 5. Padding was required for the longer eps, (like Columbo’s) and the series suffered that season. Serling was also disappointed in the Night Gallery series which followed the Twilight Zone. Some of them are excellent, and some…not so much. Usually the best episodes of both series had more of Sterling’s involvement in them. I also recommend Serling’s “Patterns” and “Requiem for a Heavyweight”, in addition to his small screen work.

All this being said, I will still watch the worst Columbo’s, Griffith shows, T.Z.’s, Night Galleries, and many other series from my favorite era (1950’s – 70’s) before I waste my time on most of the schlock that passes for entertainment in today’s clown world.

C’est la vie.

Yeah Columbo is mediocre; that is why this fellow wrote a manifesto on it 50 plus years later and eveyone is discussing it. Compare to the shows its own age , shows made since and shows made now, it is a star.

Excellent point, pking! And the first line made me burst out laughing.

This is the best comment of them all.

NBC-era Columbo episodes are like watching lean, mean, surly Elvis in 1955, though a few of those episodes are more like the cheesy 1960 movies he made, still watchable, but….meh.

ABC-era Columbo episodes are reminiscent of 1970’s bloated Elvis, wearing Liberace-style capes, doing those bizarre karate kicks on stage, with black sweat from his hair dye dripping on his super-wide bell bottoms…..then posing with President Nixon while they discussed the ironic ‘war on drugs’, while Elvis was under the influence of literally hundreds of medications from his Dr. Feelgood and Memphis Mafia toadies.

Episodes like ‘Last Salute to the Commodore’, ‘Murder in Malibu’, and ‘Columbo Likes the Nightlife’ are like Elvis staggering in his Graceland bathroom on August 16th, 1977.

Interesting choice of comparisons. I mostly disagree with them, but it’s a very odd, creepy and, yes, interesting choice you made there.

FIrst: thank you for all the great commentary.

Second: all the good insights have stirred some ideas. There is a Columbo formula–introduced, and then perfected in the early seasons. Those episodes offer a particular type of pleasure, with the ones most ably embodying the formula, often considered among the best.

But as with most any series/sequence of aesthetic products, the formula undergoes change. Questions are asked: what can we do now? How can we tweak or modify the formula? How can we stand it on its end?

With regard to Columbo, such episodes are recognizably in the Columbo tradition, but liberties are taken with the formula, with ambiguity sometimes being introduced. TROUBLED WATERS is the formula on a cruise ship, like a mystery set on an island or other contained location. FORGOTTEN LADY has a killer who does not remember that she killed someone, so Columbo’s interactions with her are not with an antagonist who is trying to deflect/mislead him, but with someone who genuinely does not know what she has done. In these cases (and others), the formula is opened up–the paradigm still clearly visible, but being riffed on.

Falk’s performance also changes as the series progresses. He too perfected a performance of Columbo early on, and then opens it up, and plays with his audience’s expectations of how the lieutenant behaves.

I watched DOUBLE EXPOSURE the other evening, and I was struck by how formula-abiding both the episode and Falk’s performance were. Watching the episode in light of this discussion, I realized that my slight boredom had to do with how closely the episode hewed to the Columbo formula. As good as it was, and as excellent as Falk’s acting was, there was a flatness to it for me. I recognized the work’s quality, but understood that I prefer looser-limbed episodes, where both formula and performance are played withriffed on.

Which is a long-winded way of saying that any estimations of the quality of Columbo episodes will be based both on objective criteria–writing, direction, performance–and also on the more subjective standard of a viewer’s embrace of/tolerance for deviations from an established/perfected artistic formulas.

I will always love FORGOTTEN LADY. In terms of objective criteria: the writing is sound, Harvey Hart’s direction is supple (he was not always liked by producers, since they felt he brought a more filmic approach to television work, resulting in footage more difficult to re-edit at will while maintaining coherence); and the performances are superb.

I could write the same about DOUBLE EXPOSURE, but what puts FORGOTTEN LADY ahead for me, is the variations it plays on the Columbo formula. DOUBLE EXPOSURE plays it straight and does not stray, but FORGOTTEN LADY opens things up. So while I can praise both episodes for their technical accomplishments, my own preference for variations on a theme will cause me to adore FORGOTTEN LADY, and regard it as one of the series greatest accomplishments.

That flexibility in formula you mentioned is the aspect that puts both “Double Exposure” and “Forgotten Lady” among my favourite entries. The first is a prime example of the “classic mould” at its most riveting, the second a most felicitous departure from the norm that successfully introduced new issues into the series.

“Double Exposure” is my favorite episode I think. The murder method isn’t flawless, but so much of Columbo’s suspicions of Keppel are circumstantial at best.

But what really shines for it is the absolutely tour-de-force turn by Robert Culp. He knows Columbo is onto him from the conversation in the grocery store, and the episode just keeps getting cattier and mousier from there. I love snarling Culp from “Crucial Game,” But this performance is my favorite of his. He’s so slick, so cool, and really doesn’t try to inject himself into the investigation unlike some of the other killers. He’ll bounce theories when Columbo hounds him, but mainly he just wants to flex his mental superiority over Columbo before making him go away.

In fact, this is one of the few episodes where Columbo works overtime to GET Keppel involved in the “investigation.” It’s no clearer than in the scene following Roger White’s death. He knows Columbo knows he killed White, and knows that Columbo is only there to try and trap him, and yet he not only ends up gleefully tagging along, but he once again “wins” the battle, as Columbo fails to trap him yet again.

Even in the brief moment on the golf course when Keppel loses his cool, he still hasn’t lost it. He’s briefly pissed but almost immediately reminds Columbo he hasn’t got jack on him, and after a golf cheat, seemingly goes on to play a relaxing under par game after Columbo leaves.

And the best part? Even when Columbo has Keppel dead to rights, he still hasn’t fully won. Keppel gleefully gloats that only Keppel’s own technique allowed Columbo to beat him. It doesn’t even seem that Keppel is that bothered by the fact that he’s going to jail for a long time. Like even though he’s lost, he’s still won, because Columbo couldn’t nail him on his own.

It was neck and neck between Culp and Cassidy for my favorite killer until “Double Exposure.” That episode sealed the deal for me with Culp as my favorite baddie. In every episode, he seems to be relishing the individual roles, but Keppel is the role where he appears to be relishing every minute from start to finish.

Really good post … Double Exposure is all you say.

For me, Culp and Cassidy are still my two number-one killers. But you make great observations, and I liked all of Culp’s episodes very much.

“Double Exposure” literally crackles with tension from the let-go.

One of my top three episodes …

Another stray thought to chew on:

“Columbo” is entertainment. Evaluating an art form is more than a counting exercise of Great/Good/Bad, as Zuzel has done. If I listened to every single David Bowie song (catalogue of 26 studio albums, many live albums), labelled every song

Great/Good/Bad, then counted how many were in each category, I might conceivably return with an assessment that Bowie Is Mediocre. That’s not being an intelligent critic, that’s being short-sighted. As I noted earlier, Zuzel’s numbers metric is a valid way of assessing a product’s overall value – if that product was pizza or blenders or a players’ batting average. Assessing art the same way we assess General Electric products isn’t incisive or perceptive, its simply lacking imagination.

Glenn — I couldn’t agree with you more!

I totally agree!

I believe you nailed it, dear Glenn.While the arguments may be generally sound, the method employed seems rather quantitative for its object.

My personal Bowie playlist has 83 songs. He recorded at least (give or take a handful) 420 studio tracks. I guess the verdict is in. Geez, and all this time I was stupidly thinking that Bowie was a genius, when he was indeed, like “Columbo”, “mostly mediocre”.

Me too! I’m gonna have to rethink my very positive view of Bowie now. I wish that wasn’t pointed out here. I was a big fan of his. But stats are stats! I can’t kid myself any longer. Anyone want to buy some old LOs?

Nicely put!

Our favorite police lieutenant is certainly not above criticism. Like most fans, I find a few of the episodes cringe-worthy in spots. But this reviewer goes much too far, in my view. It’s one thing to say the series had a few clunkers; it’s another to say it had only a few good ones.

I’m reminded of a book I read years ago about Simon & Garfunkel that dished little jabs at an alarmingly high number of their songs. The tipping point for me was when the author called the song Bridge Over Troubled Water “fake piety in the Oscar Hammerstein mold.” Seriously? Why even write about them if you feel that way?

Nevertheless, it was interesting to read a different POV, so I’m glad you shared this article. I read the whole thing, btw. Always up for some responsibly argued dissent!

A lot to agree with here and a lot to disagree with, but as to the basic point (on reviewing, the series as a whole isn’t as good as we remember it), I have to say my reaction is a big “So what?” That observation is true about almost every show ever made. No series was as beloved as the Twilight Zone, and on looking back Rod Serling reckoned that a third of the shows were quite good, a third only fair, and a third just awful…and he thought that that was about as good as you could hope for considering the constraints and production pressures of a commercial medium. Maybe Columbo should be judged more harshly because it didn’t appear every week…on the other hand, maybe it should be cut some slack because every episode was essentially a movie.

Good points about Columbo. And I’m certainly with you on Twilight Zone being beloved! 😉 Serling, btw, was notoriously harsh on himself. TZ had some duds along the way, yes, but a third of them? No way. The series would hardly be so fondly remembered six decades later if that were the case.

I’m a big fan of Twilight Zone and agree with Sterling’s assessment. The 1/3 of the episodes that were outstanding make the entire series memorable.

As I said in another post. Yes, CP only rates about 16 of 45 episodes as grade A in the original run. But the thing about Columbo is, The B grade, the C grade, and even some of the D grade episodes are still far better viewing and quality as many series’ A episodes. There are a few episodes that I’m not a big fan of, like “Mind Over Mayhem,” largely because Jose’ Ferrer is a bit wooden and seems bored, but if I’m flipping through cable channels and it’s on, I’m still probably watching it.

What helps is that even in the episodes that have poor writing, the guest star killer and supporting cast make up for a lot of ground. “The Conspirators” is a good example. Devlin’s murder plot is one of the poorest ever, and he makes so many glaring errors that he’s practically wearing a sign around his neck saying he’s the murderer. But Clive Revill is just so entertaining as Devlin that it doesn’t matter.

I feel the same about TZ. Even the less quality episodes are better than some of the best that current T.V. has to offer. And like “Columbo” it was fun seeing some of the biggest TV stars of that era getting their just desserts in the episode’s twist. Especially when said actor was playing a real jerk. Fritz Weaver is an example. He’s brilliant as the Hitleresque Chancellor opposite Burgess Meredith, and boom, at the end of the episode, he gets his karma.

Thank you, Columbophile, for sharing this indepth study of the show – learned a lot about the writing challenges from Columbo’s beginning, the fascinating Falk-McGoohan connection, Peter Falk’s efforts to continue the series after ’03, etc. Debating the merits of our favorite villains (Cassidy, Culp, McGoohan, et al), plots or scenes just underscores our affection for such a classic series & the beloved Lt! 💖

2/28 9:10pm East Coast USA, new Columbophile Blog up and running….looks slick and clean! One question, CP…..In the switchover, did the thumbs-up/thumbs-down feature get lost? That’s a good barometer feature for shy folks to express approval/disapproval without verbalizing.

The Editing feature is great. Nice job, Drtherling and Russell for the suggestion and assistance to CP.

Hi Glenn, I’m addressing that very point in a soon-to-be-published post. The thumbs up/down plug-in is apparently a DANGER to the site at present.

Yikes!

Well, Patrick McGoohan did win an Emmy for his portrayal of Colonel Rumford, so he wasn’t all terrible. Maybe he wasn’t the best fit for writing or directing Columbo episodes, given his unique ideas on such things. But I enjoyed all four episodes that he appeared in, probably because I like his acting. (At work I will frequently start a conversation with “What gives, Frank?”, using his delivery.)

McGoohan also played a spy in Ice Station Zebra… was this some sort of unfulfilled personal wish of his? It seems to pervade his acting career.

JUST ONE MORE THING: Calling Columbo a bumbler is just dead wrong. Inspector Clouseau was a bumbler. Maxwell Smart was a bumbler. Columbo NEVER bumbles. He is absent-minded, but that’s a whole ‘nother thing. He has a fear of heights, too, and he just isn’t good at a LOT of stuff.

But when it comes to detection, he NEVER bumbles. Anything he does that looks like bungling is just a method to catch the killer off-guard.

Thinking that the Lieutenant is a bumbler seems to misunderstand the entire series, which seems impossible since Zuzel WATCHED the entire series and is obviously smart. Go figure.

In sum, we have this unpretentious man with a privileged deductive mind that enables him a razor-sharp grasp on all the variables in play on a crime scene.

He wasn’t even absent minded – the business of pulling out shopping lists, etc was pure staging. More likely, some form of Aspergers – resulting in extreme concentration on the important issues – while not bothering with day-to-day crap – like statutory vehicle tests, firing range tests, dental appointments and so on.

Columbo’s Biggest Mystery – Solved!

Perhaps I’m a bit optimistic. However, now that the dust has somewhat settled on this article’s posting and I’ve combed through over 67 comments, I may be able to summarize some thoughts, and find the impetus for Zuzel’s “Columbo” assessment. (Stay tuned for the kinda-sorta-Gotcha).

In my original post now nestled in the bottom third of this thread, I noted that “New Columbo [is] an anchor dragging down the overall series quality.…perhaps this is why Zuzel comes to the conclusion that the show is ‘mostly mediocre’”. Other commenters (Richard Weill, Craig Berry, G4 and others) have expressed similar sentiments in different ways, but centered around the idea that Zuzel is wrong to assign New Columbo episodes the same critical weight as Classic Columbo. Certainly, Zuzel’s is a valid way of assessing a product’s overall value, but it seems misguided for “Columbo”. For Zuzel, it’s a numbers exercise, and with so many crappy New Columbo episodes added to the whole catalogue, the numbers tell Zuzel: This was a Mediocre show.

But many of us have no problem de-valuing the ABC episodes or throwing them out of the final verdict all together. Believe me, my love for “Batman” (‘66) isn’t some cold numbers game affected by the 26 embarrassingly awful episodes of the Batgirl Year. Nor do I judge the brilliant “Mission: Impossible” by any of its sad 35 late 80s revival episodes. Perhaps Zuzel would – I don’t.

So why does Zuzel judge “Columbo” by a numbers metric? Well, let’s say you have a favorite take-out pizza place, but over the years, it’s gotten worse. Maybe it’s the dough, maybe the ingredients aren’t fresh, maybe the sauce is watered down. Do you keep ordering that pizza? Of course not. You’re giving them money – the medium of exchange – for the pizza. But now, you’re wasting your money.

Setting aside the economics of DVD sets, streaming, etc. we don’t generally consider ourselves paying money to watch “Columbo”. The “medium of exchange” is our time. Over the years, we’ve all watched many “Columbo” eps, but 2 hours here, 90 minutes there – even if we’ve watched a so-so episode, we don’t generally say that we “wasted our time” over the entirety of our years of “Columbo” viewing.

But then, the pandemic hit – The Columbo Renaissance. Particularly during a (pick your country) lockdown, people discovered – or rediscovered – how bingeing the show could provide some solace in a challenging time. I have found at least 14 such article appreciations since March 2020. So bingeing is exactly what Zuzel did. “Inspired by Alexis Gunderson’s heart-warming column about watching old Columbo episodes with her dad, I suggested to my wife that we spend a couple of our pandemic lockdown evenings each week with the lieutenant, retracing his journey from first episode to last.”

I’ll bet those evenings started off pretty well. And I’ll bet that after about 25 of them (figuring 2/evening), Zuzel and his wife were ready to scratch their eyes out. In such a concentrated time frame, after continual back-to-back 90s episodes, it would have been very easy for Zuzel to conclude that he was “wasting his time”. And since Zuzel is a writer/critic, he had no choice but to objectively critique while he did some episode counting and consideration of how many nights he had been watching. Then he sat down at his word processor and proclaimed “Columbo Is Mediocre.”

So there’s your kinda-sorta-Gotcha. As I say, Zuzel’s approach is IMHO misguided. Don’t be shy about tossing out New Columbo to conclude that Classic Columbo was great television. If you want to arrive at that conclusion after watching New Columbo, as commenter David and others who thumbs-upped him have, that’s OK too. We can acknowledge the faults – and not just a handful of episodes, I mean the systemic faults of most of New Columbo – and all be on the same page, loving this great show.

Believe it or not, this is exactly how I watched “Columbo” during the pandemic. I had barely seen an episode, and decided to watch every single episode from Prescription: Murder to the one with the guy from “The Americans.” And yes, when I had endured a few of the revival episodes and realized how many I still had to go, I was indeed ready to tear my eyes out, but I persevered and did it.

One thing that struck me, though, was that there were a lot of bad episodes in the very first official season. And in the second. And in the third. “Columbo” was an extraordinarily uneven show. I’ve seen other people say that there are other shows like that, and it’s probably true. The whole American network broadcast paradigm of that era was to pressure every show to produce way too much product for there to be quality control. I still say that “Columbo” is surprisingly uneven even compared to these other shows.

And it really can’t be said that the show just got worse as it went along, as with so many other shows. Watching them in chronological order, I would go through a rough patch of mediocre episodes only to be smacked in the face by a masterpiece. By the time I got to Ruth Gordon, I was worried that there wouldn’t be any more great episodes, but hers was great. And there were great ones after that, several starring Patrick McGoohan, the guy Zuzel unfairly maligns. I was THRILLED when McGoohan first came back for the ABC version because all of a sudden the quality of the show went WAY up at least for an episode, and the series seemed to regain its footing whenever he returned. So I don’t know what Zuzel is talking about. I mean I suppose you could legit hate “Last Salute” so much you blame him for everything that ever went wrong!

So anywhere, buried below in the other comments, I’ve explained the ways in which I think Zuzel is right. Thing is, I reached a completely different conclusion than Zuzel after doing this. And while Glenn Stewart might be right that watching the entire season consecutively during the pandemic is the wrong way to do it, I’m glad I did it. (I also watched every episode of every “Star Trek” show consecutively — and I’m here to tell you that DEEP SPACE NINE RULES!)

My feeling is that if you watch every episode, you’re now in a great position to guide your friends to the best episodes. Because the good episodes are REALLY REALLY GOOD. And that’s all that matters! Who cares that there were a lot of stinkers — far more in the newer series than the older series yes, but also plenty in the older series too — when the best ones are so good? I’ve listed my Top 5 elsewhere, but I’ll keep listing them. This is not in order of quality but in the order they came out: