“Please forgive the condition of the room: I’m redecorating.”

Almost a year ago, Columbophile and I wrote contrasting reviews of Season 2 episode Dagger of the Mind: Columbophile loathed the episode (it’s still dead last on his ratings list); I enjoyed it as a pastiche paying comic homage to the Golden Age of British detective stories.

Now the shoe is on the other foot. Publish or Perish is one of Columbophile’s favorite Columbo episodes (read his full review here). I consider Publish or Perish one of the series’ great disappointments.

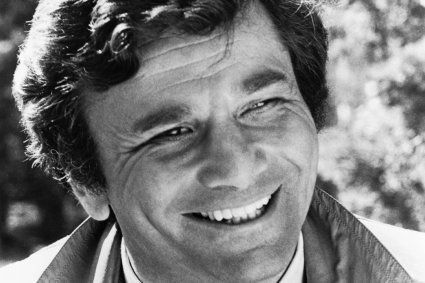

Publish or Perish!? Am I serious!? A Jack Cassidy episode? Not only a Jack Cassidy episode but, in the opinion of many, the best Cassidy episode—ranking his Riley Greenleaf above both Ken Franklin and The Great Santini as his finest Columbo appearance.

And what about director Robert Butler’s literally explosive opening sequence featuring John Chandler as Eddie Kane in a stand-out supporting performance—followed by Butler’s montage of Eddie Kane, Alan Mallory, and Riley Greenleaf, while the latter is drinking and driving his way to an alibi?

Jack Cassidy and John Chandler deliver stand-out performances

For good measure, there is also the clever casting of Mickey Spillane as Alan Mallory. [Every time I hear “Mickey Spillane,” my first thought is of the scene in the Oscar-winning film Marty where one of Marty’s friends recounts in detail one of Spillane’s bloodier passages, to which another friend responds, “Boy, that Mickey Spillane, he sure can write.”]

I’ll grant you all of these things. Feel free to add to the list. I didn’t call Publish or Perish “bad”; I called it “disappointing.” The longer your list of good things in the episode, the greater my disappointment. Because Publish or Perish has all the necessary pieces for a great Columbo. It even has the material for a first-class Columbo ending, but botched it. If only Peter S. Fischer’s “pop” clue (Peter Falk’s term for the final clue with which Columbo nails the villain) had been as good as everything else. But instead, Publish or Perish fumbled the ending completely. And from my perspective, this is an unpardonable Columbo sin.

When I judge a Columbo, I judge the ending first. A well-directed, well-acted episode cannot compensate for a bad ending. Even slick, well-written dialogue cannot compensate for a poor “pop.” And Publish or Perish’s “you don’t kill off Rock Hudson” “pop” clue—and everything in the episode supporting it—is simply lousy.

“Publish or Perish fumbled the ending completely. And from my perspective, this is an unpardonable Columbo sin.”

If we take a close look at the structure of Publish or Perish—the whys and wherefores of how the episode is plotted—I think we will see how much better the episode would have been if all the “you don’t kill off Rock Hudson” business had been trashed. [I’m sure Columbo’s NBC Sunday Mystery Movie companion, McMillan & Wife, didn’t need its star mentioned in Publish or Perish to draw an audience.]

Riley Greenleaf’s “perfect crime” has two components. First, he frames himself for the murder of Alan Mallory: Greenleaf threatens to kill Mallory (“You will die”; “I’ll see to it” that Mallory never writes for anyone else), the murderer is told to use Greenleaf’s gun leaving Greenleaf’s fingerprints undisturbed, and to drop Greenleaf’s copy of Mallory’s office key at the scene. Second, Greenleaf gives himself an unshakeable alibi for the time of the crime: a bar crawl and car smash-up (that he claims he can’t remember) quite a distance away.

Pause here and ask yourself: why isn’t it enough for Greenleaf simply to give himself the alibi? Why does he have to go further and actually frame himself for the crime? For me, the only answer is this: because it’s necessary to create an apparent adversarial relationship between Greenleaf and Eddie Kane. After all, there’s nothing particularly ingenious about creating an alibi for yourself while your accomplice commits the crime. Nor is there anything particularly exonerating about the most likely suspect having an iron-clad alibi if he well may have had an accomplice.

However, if you can create the impression that the murderer hates Greenleaf enough to frame him, you tend to focus attention away from any theory by which the two apparent adversaries are in cahoots. [Winnie-the-Pooh’s creator, A.A. Milne, may have been the first to come up with this idea, in his play The Fourth Wall (also known as The Perfect Alibi).]

So far, so good.

When Columbo learns that Mallory had the office lock changed three weeks earlier, Columbo tells Greenleaf that he believes the killer both (a) has the second copy of the new key (“if I could find the person with that new key, I’d find the person that killed Mr. Mallory”), and (b) left Greenleaf’s key behind to frame him. What is Columbo saying? If the killer knew he needed a copy of the new key to open the door, then he must have known that the old key didn’t fit the lock. Why would leaving behind a key that couldn’t open a lock frame Greenleaf? Obviously, this is all another clever Columbo gambit intended to cause his chief suspect to do or say something to incriminate himself. And it works.

When Greenleaf pulls the champagne bottle and syringe from his desk drawer, it is clear that his plan all along has been to dispose of Kane in such a way that Kane appears to be Mallory’s killer (a job presumably made easier by the fact that Kane was Mallory’s killer). No surprise here. Every Columbo fan knows that Columbo accomplices can calculate their life expectancy with an NBA game clock.

Remember Tracy O’Connor in Suitable for Framing? Tony Goodland in The Greenhouse Jungle? Shirley Blane in Lovely But Lethal? As Ray Flemming said about the first Columbo accomplice, Joan Hudson in Prescription: Murder, “Something would’ve been arranged, like an accident maybe.” Even Jack Cassidy must always have known that Eddie Kane had to go. Remember what he had to do to Lilly La Sanka in Murder by the Book?

“Every Columbo fan knows that Columbo accomplices can calculate their life expectancy with an NBA game clock.”

What Greenleaf didn’t plan on was including the new office key. Thanks to Columbo, that part is improvised—and improvisation is usually the beginning of the end for most Columbo villains.

So Greenleaf spikes a bottle of champagne, adds Mallory’s office key to Kane’s keychain, checks to make sure that his phone number is in Kane’s address book, and types a cover letter and synopsis of Mallory’s novel (in Kane’s name) on Kane’s typewriter. Then Greenleaf uses one of Kane’s grenades to blow his accomplice up. [By the way, has an explosion that loud ever caused so little damage to the bomb site? The next day, Kane’s apartment looked no worse than it looked before the blast.]

The elements of Columbo’s solution are all in place–without the added business about Mallory changing his ending so “you don’t kill off Rock Hudson.” Yes, it’s necessary that Greenleaf know enough about Mallory’s book to write a credible synopsis. But we have Norman Wolpert of the Lewis Manuscript Service to establish this. The final scene should begin, not end, with Norman proving that Greenleaf had the wherewithal to write the “Kane” synopsis.

Then the only further proof Columbo would need to nail Greenleaf is something showing that Greenleaf is, in fact, framing Kane. And Columbo has that evidence! The office key! Columbo even confirms that Greenleaf is the only person he told that “there had to be another key to fit the new lock.”

Columbo spends a good portion of this episode musing about keys – but strangely it’s not a key that ultimately condemns Greenleaf

A lot of terrific Columbos end with Columbo conning the killer into locating or planting or manufacturing a key piece of evidence, an act irreconcilable with his or her innocence (e.g., Ransom for a Dead Man; Death Lends a Hand; Requiem for a Falling Star; Swan Song; A Friend in Deed; Negative Reaction; Troubled Waters; The Bye-Bye Sky High IQ Murder Case). Peter S. Fischer wrote two of these episodes (A Friend in Deed; Negative Reaction). Why not use this ending here?

In other words, when Columbo reveals that he just changed the Mallory office lock a second time, why isn’t Kane’s matching key the “pop”? Who, but Greenleaf, could have put that key on Kane’s chain? Who, but Greenleaf and Columbo, even knew about the key? Instead, the new key is brought out at the beginning of the final scene and promptly forgotten. Instead, we get the confusing “you don’t kill off Rock Hudson” ending.

Cynics among you are probably now decrying: “But what disproves Kane didn’t come back two days later, intent on ransacking Mallory’s files, and have the new key made so he could get in?” Fair question. But you don’t need Rock Hudson to answer it. All you need is one additional fact, simple and uncontrived: that Kane’s fingerprints aren’t on the key. They’re on the other two keys on Kane’s keychain, but not on this key. How is that possible? If Kane only put the key on his chain, he would have left fingerprints. [Columbo occasionally used negative clues (the clock that didn’t chime in The Most Crucial Game; the muleta that had no water stains in Matter of Honor), but never fingerprints that should have been there but weren’t. Too bad. It’s a great clue. In a courtroom scene in my play Framed, a police witness cannot explain why the defendant’s fingerprints were left carelessly all over her gun, while all the bullets remained pristine.]

You need zero further exposition to complete this “pop.” We’ve already seen Greenleaf, wearing surgical gloves, take Kane’s keychain from his jacket, add the key, and replace it in the pocket. No prints.

Compare this to the clumsy way in which the Rock Hudson storyline was shoved into the episode. Exhibit A: the Chasen’s Restaurant scene, where we first learn about the “you don’t kill off Rock Hudson” change to the ending of Alan Mallory’s novel. Sure, the scene has its delightful “fish out of water” moments, with Columbo trading his usual hot-dog-stand lunch for the valet parking and “big menu” of a swanky restaurant, and forgoing the menu’s sweetbreads financière and trout amandine for non-menu chilli.

But there is no credible investigative reason why Columbo ever goes to Chasen’s to meet Geoffrey Neal and Eileen McRae. On paper, it’s to ask them if they can “think of someone who might want to frame Mr. Greenleaf.” Really? You mean the framing of Riley Greenleaf isn’t just a ploy Columbo is using with Greenleaf, to put him off his guard? You mean Columbo is taking this theory seriously? For the reasons I gave previously, I find that hard to believe.

No, the scene exists for only one reason: exposition. So Geoffrey and Eileen can tell Columbo about the changed ending—something of no relevance to anything Columbo is then investigating.

But to top it all off, the Rock Hudson ending has a major flaw. How does Riley Greenleaf, listening to Mallory’s dictation, write a synopsis containing the new ending? According to Eileen McRae, in the new ending, the hero “says goodbye to the material world, and goes off to a monastery.”

Before being shot, Mallory begins to dictate this ending. He dictates: “He knew which way he would have to turn. Out across the plains was the monastery of St. Ignatius, offering him hope and a chance to wash away the wounds of war that had brutalized him.” We don’t know if he actually goes there, if he reconsiders, if someone or something intervenes, because Mallory never gets the chance to write the end of his book. But what we do know is that “the monastery at St. Ignatius” is part of the final tape Mallory is dictating to, as he says, “wrap it up for the first draft.”

So how did “the monastery at St. Ignatius” dictation get to Norman Wolpert and hence to Riley Greenleaf? Columbo seizes both the tape recorder and the final tape. He plays part of the tape to Greenleaf at the police station. The final tape never gets to the Lewis Manuscript Service.

Publish or Perish is one of two 1970s Columbos solved because a writing contained facts unknown at the time it supposedly was written. Identity Crisis is the other. I’m not a fan of either solution.

Oh, to have been a fly on the wall at the Publish or Perish story meetings. Given that Fischer wrote the “only one person, beside myself, knew this” ending for his superb A Friend in Deed script, later in Season 3, there’s reason to suspect that he may have done so here first—that the new office key was his initial “pop” clue for Publish or Perish. It’s only a guess, but a reasonable one. Why wasn’t it considered enough? How did the Rock Hudson business not only barge into the script, but become the “pop”?

“Prior to Publish or Perish, the only Season 3 Columbo with a tack-on ending was Lovely But Lethal, an episode acknowledged for its mediocrity.”

For me, it wrecks the episode. It’s a flawed ending forced into the story, with a lot of cumbersome exposition required to explain it, rather than a logical ending flowing naturally from what’s already in the story.

Compare this ending to the last three episodes reviewed here: Any Old Port in a Storm, Candidate for Crime, and Double Exposure. In the first, the murderer is caught because his murder plan left an exceedingly subtle clue behind that only the murderer could detect. In the second, the murderer had to try one last time to arrange an unsuccessful attempt on his life. In the third, the murderer’s modus operandi was used on him. See the difference? See how these solutions are baked into the core of the story?

Prior to Publish or Perish, the only Season 3 Columbo with a tack-on ending was Lovely But Lethal, an episode acknowledged for its mediocrity. The fact that Publish or Perish is not similarly viewed is a testament to Jack Cassidy, John Chandler, and Robert Butler’s ability to distract us away from Publish or Perish’s prominent story flaw.

It’s an awkward achievement, but an achievement nonetheless.

Richard Weill is a playwright, lawyer and former US prosecutor based in New York. A Columbo fan since the show first aired, he is an occasional guest contributor to the Columbophile blog

Read Columbophile’s take on Publish or Perish here.

Which camp do you sit in? Is Publish or Perish awesome or a let down? Let us know below?

“What do you make of this second opinion, Riley?” “Frankly I’ve had this review up to HERE!”

It is strange because writer Peter S. Fischer penned some of the best ironic endings in the series. Without knowing him, it seems as though he was deliberately going here for a conclusion that was more mysterious and abstract, rather than tangible and mundane. As It’s been implied, it could just be he didn’t want an ending that was too similar to his superior “A Friend In Deed.” Makes me wonder which episode he wrote first, despite the fact that POP aired before AFID. This was his first year as a Columbo screenwriter and some critiques have even suggested that this was one of the unusual cases that may have been served better with a 2 hour treatment rather than 90 minutes-maybe, maybe not. Guess will never know.

Richard-I think your analysis of Publish or Perish is the best I’ve ever read on this good episode that could have been great. I saw this when it first aired when I was 16 years old, and even at that age the ending didn’t feel quite right. I never noticed Riley Greenleaf failing to ensure Eddie Kane’s fingerprints were on the new key before adding said key to Eddie’s key chain. It would have only taken a second to have sleeping, drugged Eddie touch the key. I wonder if this was a mistake in the writing or directing? Are we to assume that Kane’s prints are on the key but the director just didn’t show this? We know a thorough detective would look for both prints that should and shouldn’t be there. The missing prints nail Greenleaf for both Mallory and Kane’s murders-two birds with one stone; a rarity on a Columbo where a chance for maximum irony should not be ignored by the creative team. Maybe this episode could get a re-write for the stage or a reboot some day. What I liked best about this episode was Jack Cassidy’s performance. Probably the best performance by a villain in the entire Columbo series. Also, this was the most film noir episode of the series, a fast pace, crackling homage to noir.

Thank you, Anthony. Coincidentally, I was thinking about irony earlier today — trying to test my theory that ironic gotchas were far more frequent in ‘70’s Columbos than in the ‘90’s episodes. The solutions to latter shows always seemed to lack something. And I think that something is irony.

My main issues is with the key switch. I agree the ending change seems less solid, making the key/lock switch all the more crucial.

Here’s the problem I see…When Greenleaf finds out the lock was changed, Columbus specifically says “how did the murderer get in?” A good question, right? That should have haunted Greenleaf… When he did talk to the murderer, Eddie, why didn’t Greenleaf ask him how he got in? And given that Eddie dropped the other key, what possible reason would Greenleaf have for getting a new key made?

I understand for us (or at least myself!) it’s hard to keep track of these keys and locks, but Greenleaf this is what he is going to obsess over. Would he really get a key made, so that the story is what-the murderer opens the door with one key and drops a different key that doesn’t fit to frame Greenleaf? In Greenleaf’s story, Where does Eddie get this new key from if not from Greenleaf’s car?

it’s brilliant that Columbo would change the lock on his own. But I don’t think he really gave motivation for Greenleaf to to create a new key.

Can someone tell me what I’m missing? And if I am onto something, as a thought experiment how could the story be altered for a better gotcha?

When Greenleaf next spoke to Eddie (after learning about the new lock), he did ask, “No trouble getting into Mallory’s office?” Eddie answered: “The door was open, but I left the key on the floor anyway, like you told me.” But whatever Eddie’s explanation, Greenleaf knew he had to plant the key to (what he believed was) the correct lock on Eddie.

Ah I forgot that somehow, Greenleaf asking about whether Eddie has trouble getting in…

But one more thing…;)…once Greenleaf realized the door was open when Eddie murdered Mallory, then he had no reason to plant a key! He had succeeded better than he could have hoped. Remember his goal is to make Eddie look like he is trying to frame Greenleaf. Eddie steals the key, finds the door open, so doesn’t know the key doesn’t fit. Eddie still drop the key he took from Greenleafs glove compartment. Clearly this was no accident, the key was proven not to be used to open the door, but was most likely planted there to frame Greenleaf. Perfect!

But now to plant on Eddie a key he clearly didn’t need is bad for Greenleaf for several reasons. It puts Greenleaf at risk as we later see. I remember gut-wise thinking ‘that’s a bad idea to get a locksmith, better to be less involved and plead ignorance’. But even if Greenleaf didn’t consider this, it also only weakens the argument that Eddie framed Greenleaf. If the locks were just recently changed and Eddie just got the key, say from Mallory, Eddie would know that Greenleafs key likely doesn’t work, making dropping Greenleafs key much less convincing way to frame him. And third, how would Eddie have so recently gotten a new key from Mallory? This suggests a much closer relationship between Eddie and Mallory, or suggests a recent theft that didn’t actually happen, and I’d argue either one unnecessarily confuses the analysis.

Maybe Greenleaf simply made a mistake…but for such an intricate planner who types forged letters to make a frame-up…I don’t know.

I think I agree. I’ve watched the PorP a good while ago, but I remember I didn’t quite understand what’s the catch there. Maybe I’m just too dumb, but the changed-book-ending was not solid in my view. As an evidence. I also remember that pretty lady saying aboute the change, and I couldn’t get it WHY should we (and Columbo) trust her at all. She could be a muderer as well an try and tangle facts&evidence by her words. Of course, we the viewers had known that she’s no criminal, but Columbo has no such comfort. To be honest, the whose-was-the-key solution is a bit complicated to me too, but would be more believable than some uncomplete-literature-script case solution.

great episode on the whole, but i agree the ending which is rather confusing and flawed spoils what is a classic its similar to identity crisis ending which worked better

on the whole i prefer identity crisis. i just think the ending blends in better wher as with publish or perish it didn’t..

Richard, your review of Dagger of the Mind caused me to take another look at it with fresh eyes. I appreciate that episode now,for something besides guest star Bernard Fox.

You may be right about the key clue; I watch these on Cozi and ME tv so if I get lost I’m not sure if a scene has been cut, etc or I’m missing something.

However, I judge my Columbos on entertainment value and this episode is hilarious. My favorite Jack episode is Murder by the Book, but here Jack Cassidy is at his diabolical best. He is sneering out lines such as ‘buy yourself a personality’, ‘stinkin joint’, and ‘you, and this place,deserve to be in the valley. He is greedy, condescending, evil, arrogant and quite oblivious to Columbo’s genius.

Also I love the car accident and older couple.

As to why the small ‘holes’ don’t bother me I’ll refer back to this exchange:

Columbo-You don’t have any answers?

Riley-No not a one.

ps “EDDIE” was also a bad guy in the 80s classic..Adventures in Babysitting

the worst ending is based on unequal number of goldfish in three tanks below a disco dance floor. now peter, you were a great actor but the writers made you look silly.

Great piece. The writers did employ the clue of an absence of fingerprints when there ought to have been some, in A Friend in Deed, when Columbo is searching the first victim’s bedroom.

I was referring to “pop” clues, Frank. In “A Friend in Deed,” Columbo did note the absence of fingerprints on the handle of Janice Caldwell’s closet door, prompting Hugh Caldwell to “explain” that Janice always kept her nightgown folded under her pillow (and therefore had no need to open the closet door to change for bed). The clean handle may have raised an initial suspicion — although, because it never led to much, I’m not sure it even qualifies as the “click” (a term I explained in my last contribution to this blog). But it certainly wasn’t the final “pop.”

Thanks, Richard. I thought there was also something in there about her prints not being on the phone, but it’s been a while since I watched AFID, so it looks like I need a refresher. Thanks for giving me the excuse. F

Yes, you’re right again. Caldwell claimed he called his wife, but her prints were not on the phone. Commissioner Halperin suggested that the “burglar” wiped the phone clean, but this made no sense to Columbo, as all the evidence pointed to the intruder wearing gloves.

On reflection, this fingerprint anomaly would be the “click” of the episode. Thanks for keeping me on my toes.

Great read, but still one of the most entertaining episodes, just my opinion. Cassidy is quite maniacal when yelling at the couple after the fender bender. The woman in the van (that Riley suggests call a plastic surgeon) is Maryesther Denver, who is just another Columbo alumni (Columbni? lol) that I’ve come across due to my penchant for 70s TV/Movies. I was viewing a movie called “Wicked, Wicked” (1973) and she plays the organist who basically supplies the chilling background music. One look and I knew it was her, no doubt about it!.. Another connection between this episode and “Wicked, Wicked” is both were filmed using “Duo-Vision” or Split-screen” (or the montage you’re referring to when Kane kills Mallory while Riley executes his alibi) For me, it’s one of the most suspense filled moments in any Columbo, and really satisfies the palate when it comes to 70s crime sagas. Not to mention that spotting Maryesther Denver in another role blew my mind and I just had to tell somebody! I figured that somebody on this forum may appreciate that tidbit of useless information! lolol …Cheers, all!

More outstanding insight, thanks Richard! I’d never considered the incongruity of a lack of Kane’s fingerprints on the newly made key until now, but a very relevant observation. The reference to the monastery in Mallory’s dictation doesn’t trouble me at all, though. I’m happy to assume that a more detailed reference to the central book character’s decision to begin life anew at St Ignatius was referenced in the previous chapter (which reached Greenleaf), and what we heard on the tape was merely reiterating that decision.

Thanks, CF, for your kind words. But in my view, the best Columbo solutions shouldn’t require you to make assumptions. We were told that Mallory changed the “final pages” of his book (“Allen was planning to kill the hero off in the final pages”). Greenleaf certainly never read the final pages.

Riley never received the final transcript, but this could easily have been a redraft of the chapter, or an epislogue to follow on from the previous chapter’s ‘revelation’ that the central character would go to the monastery. However much the episode writers could have improved this ending, the fact remains that Riley *did* know about the monastery ending through whatever means; he knows how Mallory works; and was satisfied that he had the whole plot synopsis in hand, otherwise he surely would have waited to have Mallory slain. So if the final synopsis sounded like Mallory dictated it himself, as Miss McRae says, he must have previously dictated the monastery section, regardless of what wee hear in the last, fatal transcript. I’m totally happy to accept that, so it spoils nothing for me.

Now that you mention it, yeah, how *did* Riley know about the changed ending if the book hadn’t been finished yet? My guess, and it’s only a guess is that a revised outline or synopsis was in writing somewhere, and Greenleaf got his hands on it through the manuscript service who may have had a copy. I still say had Greenleaf just had Eddie do the job, leave no evidence, use a different gun that couldn’t be traced to Greenleaf, don’t say what he did in front of witnesses, and still do the drunk car accident in Encino there would have been nothing to connect Greenleaf save for some suspicion but no evidence at all.

The irony is they had the “pop” and gave it away. About 2/3rds? of the way through, they reveal the locksmith’s actions. Since there is no way that Eddie could have known about the switch, Riley would be trapped with his alibi. changing the lock and yet the key being left with the new key being on Eddies key ring was the “pop”. In fact if anything, I would argue the ending was rushed and in a reversal, this was/should have been a 2 hour Columbo. They tried way too hard to make it fit the 1:30 format.

The Great Santini, IMO, is Jack Cassidy’s best Columbo role.

I must say, this review spells out the reasons for my own disappointment in exquisitely detailed fashion. This was actually the last Jack Cassidy episode that I saw, and always felt that it just didn’t measure up to the other two, and now I have a much better understanding of why. Watching it just last week I believed that the key business would have been a far better ‘gotcha’ than the Rock Hudson conclusion, all the right elements present, one more rewrite and a classic might have resulted. So much of it is right that a weak wrap can leave a bad aftertaste in one’s mouth. On the other hand, I never liked Dagger of the Mind.