Being the 50th anniversary of Columbo’s first season airing, 2021 was a pleasingly big year for new books about our favourite Lieutenant.

Alas, with the exception of David Koenig’s Shooting Columbo, my daughter’s illness last year meant that the release of these tomes largely passed me by, and any attempts to promote them were severely curtailed – a series of wrongs I will right here and now. These aren’t reviews, more of an overview and an attempt to raise awareness of reading opportunities you may have missed. Needless to say, I doff my cap to the writers of these (and all) Columbo books, who show magnificent dedication to the cause of keeping the Lieutenant’s legacy alive.

NB – I always advocate buying at your local bookstore if possible, so ask there first! I have, however, included links to the books on Amazon where possible, to provide convenient options for a global readership.

Columbo: Paying Attention 24/7, by David Martin-Jones

Released in hardback in 2021 before a paperback launch in March 2022, David Martin-Jones (Professor of Film Studies at the University of Glasgow) considers how Columbo’s dedication to paying attention to the smallest things helps him solve ‘perfect murders’ onscreen. Through this lens, Martin-Jones also examines how societal attentions are channelled – including via TV and the internet – to influence all aspects of our lives.

Featuring commentary on how Columbo is able to remain fixated on his cases 24/7; how he is able to overcome unfamiliarity with cutting-edge gadgetry to “upgrade” his knowledge and pay attention even more effectively; and his role as an anti-establishment figure who is, atypically for the 70s’ era in particular, in tune with the social tensions of the day, the book even features a foreword by Columbo superfan Stephen Fry!

At time of writing, I’m only part-way through reading this. Its academic nature makes it occasionally hard going, but if the reader takes a leaf from the Lieutenant’s own book and pays full attention, there’s much to stimulate their thinking.

Published by: Edinburgh University Press

Available in: paperback and hardback from $24.95 /GBP 17.75

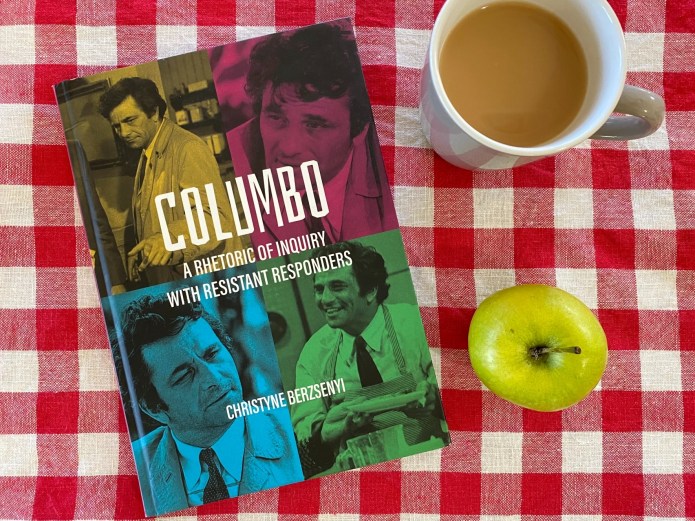

Columbo: A Rhetoric of Inquiry with Resistant Responders, by Christyne Berzsenyi

Much delayed by the COVID pandemic, Christyne Berzsenyi (an Associate Professor of English at Penn State Wilkes-Barr) saw her academic Columbo book finally published in mid-2021.

Covering such subjects as the literary influences behind the character (including some fascinating insight into the similarities between Columbo and Crime and Punishment’s Porfiry Petrovic); the enduring legacy of show and character; Columbo’s investigative style and methods of questioning used to achieve differing outcomes; his approach to dealing with women; and an examination of audience / villain relationships, there is a load of subject mater to sink your teeth into. Berzsenyi even questions whether we should consider some of the Lieutenant’s acts of “villainy” an aspect of his character that prevent him from truly being considered a heroic figure.

As an academic study, this book is necessarily less accessible than some to a casual fan. Nevertheless, there is plenty of food for thought for Columbo die-hards, although a few factual howlers, such as claiming Nora Chandler inadvertently killed her personal assistant Jean in Requiem for a Falling Star (Jean was the intended target all along); that gossip columnist Jerry Parks was Nora’s estranged husband (they were never married); and that Leon Lamarr had no children of his own in Death Hits the Jackpot (he has at least one son and one daughter) do rather leap off the page.

Publisher: Intellect Books

Available in: Kindle; paperback; hardback from $22.99 / $40 / $93

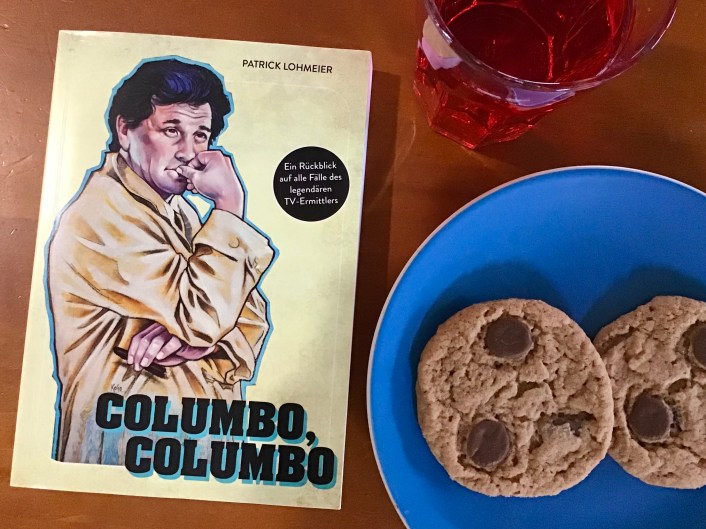

Columbo, Columbo, by Patrick Lohmeier

A German-language retrospective of the entire Columbo series, Patrick Lohmeier’s Columbo, Columbo initially came about via a crowdfunding campaign in 2020, with a black-and-white paperback version going on general release in 2021.

Not dissimilar to the Columbophile blog, Patrick’s approach was to pen a mix of critical analysis, and production trivia, while including specifics about the German dubbing and occasional censorship. He was good enough to send me a copy last year, and while my Deutsche isn’t nearly good enough to enjoy it to the max, I can tell you that it’s a very accessible read that will offer German-speaking fans of Columbo no shortage of material to enhance their understanding and appreciation of each episode.

As a lover of Columbo artwork, I’d also like to put it on record that the cover illustration by Kolja Senteur is a real gem!

Published by: Bahnhofskino

Available in: paperback from EUR 21.99 / $24.30

And the best of the rest…

These books were published at various times 1989 and 2021, but represent sensational reading for Columbo fans. If there are gaps on your shelf, do consider filling them with any and all of these wonderful works…

The Columbo Phile, by Mark Dawidziak

The granddaddy of all Columbo books, this masterpiece was originally released in 1989 – just after the show’s ABC comeback – and was a labour of love years in the making. Offering insight and analysis on all ‘classic era’ Columbo episodes, as well as interviews with cast and crew – including recollections from Peter Falk, Patrick McGoohan, William Link, Leonard Nimoy, Roddy McDowall and many more – Dawidziak’s book remains The Holy Grail for purists.

Although the original version is now out of print and can be expensive to lay your hands on, an affordable 30th anniversary reprint was published in 2019, complete with 10,000 words of new content. A must-read.

Shooting Columbo, by David Koenig

Released in 2021, this is the most important Columbo book to be published since The Columbo Phile. Koenig was permitted unprecedented access to the show’s archives, as well as interviews with directors, writers, actors and producers involved, to provide masses of behind-the-scenes intel on the production of all 69 episodes – much of which has never been published before. Ever wondered why Old Fashioned Murder is such a shambles? Puzzled by Tanya Baker’s absence in Double Exposure? Not sure whether Peter Falk really did the hill fall from Greenhouse Jungle himself? Then this book is definitely the one for you…

Columbo Under Glass, by Sheldon Catz

Although I’ve never actually read this book (don’t judge me!), I’ve heard it’s a quality read that pays particular emphasis on the “click” clues Columbo picks up on to first arouse his suspicions, and the “pop” clues that prove the villain’s guilt. The book also features essays on a range of subjects including his sympathetic relationships with villains, his moral code and the supporting cast. Incidentally, Sheldon Catz served as chief writer and editor of The Columbo Newsletter quarterly fanzine between 1992-2002, so is a highly qualified commentator on the subject. Features a foreword by Mark Dawidziak.

Cooking with Columbo, by Jenny Hammerton

Lovely idea and a really fun cook book featuring dozens of favourite recipes from stars of Columbo! As well as some darn tasty chilli recipes, there’s something here for every occasion from fine dining to light snacking. I was pleased to provide the foreword to this book and recommend it highly. Get amongst it!

Just One More Thing, by Peter Falk

Anecdotes from Peter Falk’s life (including plenty on Columbo) are presented here in bite-sized chapters giving readers a very easy chance to dip in and out of the life of the great man. The tone is so conversational, one can almost hear Peter’s voice narrating it.

That’s all for today, folks. If you’re the proud (or otherwise) owner of any of these publications, please share your opinions on them in the comments section below to guide would-be buyers towards sensible purchases.

The next post on the blog will be the highly anticipated review of No Time to Die – many a fans’ absolute least favourite episode. I’d expected to have published this already, but I slipped into a DISGUST-INDUCED COMA after watching it again a couple of weeks ago and am only just recovering my strength. Keep the faith! And I’ll see you all soon…

I recently got a book by Rodney Marshall, THE ART OF MURDER; Classic Columbo: The early NBC years. It covers the two pilot movies and the first five seasons. I haven’t finished it yet, so it may explain why he didn’t just do the whole seven seasons.

It’s a fairly interesting read. He covers each episode by using a set of categories–Title, motive/means etc, guest characters and the actors playing them, locations, key scenes, Columbo’s rapport with the villain, and so on. Oddly, music is not one of the categories. From these, he creates his review of the episode. He notes that some of his opinions are in the minority, but he provides a good explanation for doing so.

I must mention one observation he made that really knocked me for a loop. It concerns the episode “Death Lends a Hand”, involving Leo, the investigator that Brimmer assigned to the Kennicut case. Brimmer knows that eventually Columbo will want to interview Leo. (“Yes, her husband was right about her. The old ‘private lessons’ schtick. I got plenty of evidence. But why are you asking me? I gave Mr. Brimmer a full report.”)

Brimmer hastily arranges to send Leo out of town on an assignment that Brimmer likely made up then and there. Simple, yes?

Mr. Marshall’s notion is that Leo is Mr. Brimmer’s professional assassin.

He got this from the scene where Leo is at home, happily playing with his son, when the call comes from Brimmer. Mr. Marshall apparently interpreted this scene as a subplot demonstrating the dark side of Brimmer’s agency. I will grant you that in a movie thriller, they might use the heavy irony of the devoted family man getting a call and dutifully going out to kill someone, but this is a Columbo episode! Even if Brimmer did have a secret department offering killers for hire, would he use them on mundane infidelity assignments?

I have spotted a couple bloopers so far, but this one was really over the top!

From David Koenig:

I’m excited to announce that Shooting Columbo has just been released in an expanded, updated paperback edition! The hardcover edition is now out of print.

[https://www.amazon.com/dp/1937878120](https://www.amazon.com/dp/1937878120)

Columbophile points out one howler, with Berzsenyi’s book

“claiming Nora Chandler inadvertently killed her personal

assistant Jean in Requiem for a Falling Star”. An easy

slip-up to make, I think.

Others now have noted the wrong victim ‘flaw’ of the episode,

Columbophile, myself, and this book’s author. The episode

might have been better if indeed Jerry was the intended victim,

and Jean the unintended one. In terms of Nora’s character

anyway, even if the logic wouldn’t work as well with Jean’s death

being accidental.

My $55 purchase has arrived!

“Columbo: Class Struggle on TV Tonight” author Lilian Mathieu is a sociologist, and his French original was written in 2013, but as Rich notes below, has just now been translated to English (Jan 2022). At 80 slim pages, it’s more of a dissertation than a work of popular culture you’d see from Greenleaf Publications or find at Chandler’s Books (“Serving California, Open Evenings and Sundays”), so alas, no Columbo photos or cover art.

The theme of “Columbo” as a Clash of the Classes is by now a familiar one – that’s to be expected when the monied murderers are taken down by the common Everyman. And even though Link and Levinson didn’t have class warfare social commentary in mind, only creating dramatic television between Columbo and the villain, Mathieu correctly remarks that the show “invites the audience to perceive and interpret their confrontations in those [class] terms. This is one of the keys of the popularity of the series”. Although it could not have been forecast at the time, Columbo’s take-downs of the 70s Elite is very morally comforting in 2022, when the divide between the haves and have-nots is even greater than it was 50 years ago, and wider than what Mathieu saw in 2013.

But I wish Mathieu had done a bit more with this theme. Precious pages are spent cataloguing the many ways that Columbo is viewed as culturally inferior by the haughty baddy, including (but not limited to) examples of disrespect, symbols of power and social domination, resource inequality between Columbo and villain, shows of condescension and contempt, and Columbo’s “petty bourgeoisie” tastes. The class imbalance is laid out very thoroughly.

But there are few unique takeaways from Mathieu on this premise. Most interesting to me, as a former History teacher, were too-brief paragraphs about the “contentious context” of 1968, where unrest and conflict popped up in various hotspots around the world and the U.S. This was the year of “Prescription: Murder”, and Mathieu argues that “Columbo’s success directly relates to the rebellious mood…” This “rebellious mood” aligns with the class cleavages of Rich v. Poor.

Another intriguing point from Mathieu is that Columbo’s detecting success stems from his Everyman status, and his ability to recognize the crime clues that arise from discrepancies in mundane, ordinary behavior: the new shoes the burglar wears, the nightgown under the pillow, the freshly-opened mail. “The class revenge that accounts for Columbo’s success is not only a victory of the poor over the rich…but of the daily existence shared by the vast majority of people… over the ruling class. The resources of ordinary life, experienced by an ordinary cop married to an ordinary wife, allow him to defeat them.”

I also enjoyed seeing Mathieu trace Columbo’s detecting style from an 1874 Italian art historian to Sigmund Freud to the crime fiction of Sherlock Holmes and Commissaire Maigret. It left me wanting more…more than just one thing.

The next episode to be reviewed, No Time to Die, is a bad episode but it provides clarity about Columbo’s attitude toward wealth. We watch Columbo enjoy an opulent wedding and delight that his nephew is marrying into the family of a shopping center magnate. The bride has her own money too. There’s no “class revenge” at all.

In the book, Mathieu acknowledges that Falk (per an interview with Mark Dawidziak) insists that the Columbo character has no animosity toward the upper class. That may be true, and it aligns with Link and Levinson’s rationale, but viewers will read into the show what they want, and the “class revenge” take is now a common one. That interpretation loses the nuance, but ironically, has fed into its ongoing popularity.

And nobody wants to remember “No Time To Die” anyway.

I think Columbo’s just happy for his nephew…

Jeff Greenfield wrote a piece for the Sunday New York Times in 1973, entitled “Columbo Knows the Butler Didn’t Do It,” all about this very issue. As Greenfield said then: “There is something else which gives Columbo a special appeal — something almost never seen on commercial television. That something is a strong, healthy dose of class antagonism. The one constant in Columbo is that, with every episode, a working-class hero brings to justice a member of America’s social and economic elite. The homicide files in Columbo’s office must contain the highest per‐capita income group of any criminals outside of antitrust law.”

The Columbo article in “Reading the cozy mystery : critical essays on an underappreciated subgenre” edited by Phyllis M. Betz,

makes a similar point. In order for Columbo to succeed as a

“cozy mystery detective”, he must be widely popular. I don’t agree

that a detective character’s popularity among readers is a requisite of successful mystery fiction.

I think both the rumpled, uber-smart Columbo, and the sophisticated, clever villains he brings down, are carefully crafted to appeal to youth, and the lower to middle classes that mostly watch TV. And the reason for the series huge popularity, then and now, among viewers many of whom probably don’t even read mystery fiction.

So while jail-bait, and sometimes lower class workers like butlers,

probably do commit most murders, they wouldn’t necessarily make a hugely popular detective television series.

To which I add, I could see that a cop with his

talents in real life would probably only be assigned

to the murders of the high and mighty. There’s

nothing implausible about that.

Rich, I think you’d agree with me on where I believe Greenfield whiffs in that piece. He later says, “This is, perhaps, the most thoroughgoing satisfaction Columbo offers us: the assurance that those who dwell in marble and satin, those whose clothes, food, cars, and mates are the very best, do not deserve it.”

That’s a pretty sweeping condemnation, and I believe that Link, Levinson and Falk would all disagree. Rather, Columbo feels that the wealthy do not deserve *to get away with murder* just because of their status. Their status has given them the comfort of deference by others and escape from consequences. But their fame, breeding and upper-crust lifestyle do not, in fact, insulate them from justice in Columbo’s world. It’s that sense of justice, not disdain for the Richie Richs, that drives our hero.

Whether unintentional, or projection, or perhaps just inelegantly written, Greenfield misses the nuance…..but so do many others.

You have to read the language you quote in conjunction with the preceding paragraph:

“Columbo knows about these people what the rest of us suspect: that they are on top not because they are smarter or work harder than we do, but because they are more amoral and devious. Time after time, the motive for murder in Columbo stems from the shakiness of the villain’s own status in high society. The chess champion knows his challenger is his better; murder is his only chance to stay king. The surgeon fears that a cooperative research project will endanger his status; he must do in his chief to retain sole credit. The conductor owes his position to the status of his mother‐inlaw; he must silence his mistress lest she spill the beans and strip him of his wealth and position.”

That’s what Greenfield means by: “those who dwell in marble and satin, those whose clothes, food, cars, and mates are the very best, do not deserve it.” As he then says, “They are, instead, driven by fear and compulsion to murder.”

Greenfield isn’t looking primarily at why the rich and powerful think they can get away with their murders. He’s looking at why they commit these crimes in the first place. Isn’t it because they know they can’t succeed on merit alone? Isn’t it because, deep down, they know they don’t fully deserve to be where they are?

[Note: Greenfield’s article was written at the end of Season 2, so should be judged based only on the episodes that preceded it.]

I don’t think it’s very difficult for Greenfield or anyone else to note that the murderers in Columbo were trying to protect or enhance their status. The question is whether Columbo solving such a murder is “class revenge” or “a victory of the poor over the rich”, as claimed by the author of the book Glenn reviewed.

The murder victims in Columbo episodes were often well off themselves. In situations where the victim was of much lower status, it was sometimes a person who made a bad choice to blackmail the murderer.

For the purposes of television drama, a rich arrogant villain is more interesting than a monosyllabic brute. But when I watch Columbo, I don’t get a sense that Columbo’s determination to solve a case is affected by the economic status of the suspect or the victim. He believes that we have an obligation to all victims to solve their murders and bring their killers to justice.

Robert Butler, director of “Double Shock” and “Publish or Perish,” had an interesting take on Columbo’s view of his suspects. Butler believed that Columbo always wanted them to be innocent. That he wanted to believe them, but a nagging discrepancy prevented that. “I didn’t read that as malicious; I read that as hopeful,” Butler said. https://interviews.televisionacademy.com/interviews/robert-butler?clip=48695#show-clips

[Apologies if this winds up getting accidentally posted twice!]

I hear what you’re saying, and I think that there’s room to interpret Greenfield both ways. Clarifying a bit by saying “these killers” instead of “these people” would have helped nicely. But I came down on my side of the fence because the overall article is so heavy on the “class antagonism” angle. You’re right, he’s looking at the rich killers’ motives and not on the “getting away with it” part – where I think Columbo’s sense of justice comes in. But I think Greenfield had the brainpower and ink space to try to do both, and didn’t. Dawidziak also notes the substantial class antagonism emphasis

Link and Levinson probably provided their famous explanation of the villains as a result of Greenfield’s article: “When the series went on the air, many critics found it an ever-so-slightly subversive attack on the American class system in which a proletarian hero triumphed over the effete and moneyed members of the Establishment. But the reason for this was dramatic rather than political. Given the persona of Falk as an actor, it would have been foolish to play him against a similar type, a Jack Klugman, for example, or a Martin Balsam. Much more fun could be had if he were confronted by someone like Noel Coward.”

Greenfield was in ’73, the Link/Levinson quote was from their 1981 book “Stay Tuned”. So…..do we take Link/Levinson/Falk at their word that class cleavage was not their intent at the time? Or did they say that because Greenfield struck an uncomfortable chord and they didn’t want to antagonize anyone?

And here’s the link for people not named Weill or Stewart to access the Greenfield piece and give it a think:

https://www.nytimes.com/1973/04/01/archives/columbo-knows-the-butler-didn-t-do-it.html

[The two links in my original comment made it impossible to post. If you want to find the two Wes Britton-William Link interviews, Google those names and click on the “Anchor” site; the first interview is 31:23; the second is 41:29.]

In the latter part of his life, William Link gave two interviews to Wes Britton. The first followed the appearance of his book “The Columbo Collection.” The second was shortly after Peter Falk’s death.

In the first interview, at about the 21:00 mark, Link says: “We played the class game. Columbo always went up against the rich, the wealthy.” He then misquotes “The New York Times” — specifically, Greenfield’s reference to Columbo being “plucked from Queens Boulevard by helicopter, and set down an instant later in Topanga Canyon” — and adds: “They were right. We played the class card, and it worked for us.” Link then explained that this was because most Columbo viewers “weren’t wealthy” and “identified more with the cop who started with nothing, who’s against these arrogant, wealthy murderers.”

In the second interview, Link says the identical thing (including virtually the same Greenfield misquotation) at around 27:20.

I do agree that “the reason for this was dramatic rather than political.” I don’t think either Link or Levinson were trying to make a political statement. They wanted to create a dramatic character whom a mass audience would root for. People root for David against Goliath. They wanted what “worked for us.” [In the second interview, right before the mark noted above, Link talks about Jack Cassidy: “He had the proper amount of contempt for the cop. … Here’s this arrogant murderer, wealthy, treating Columbo like he’s scum.” That was the ideal relationship for their purposes.]

Excellent discussion, excellent resources. Between Link’s video, the “Class Struggle” book, Link and Levinson’s comments, Falk’s thoughts to Dawidziak, Greenfield, and our own observations (thanks to Claude for contributing too), I think it plays like this:

The “Columbo” team realized that having a David v. Goliath conflict was the way to go. They recognized that the class/fame/wealth/power angle was the clearest and most consistent way to accomplish this. It was absolutely for dramatic purposes – not a political statement – but the “class revenge” element was something that resonated with viewers (ratings!), so it remained constant. For fans and writers like Greenfield, that then became the show’s guiding theme. And, it has had a residual effect over time, with the divide between the haves and have-nots now so great that watching “Columbo” 50-odd years later provides cultural comfort for the 99%. Perhaps unintended by Link and Levinson, but a residual effect nonetheless.

Columbo does not resent the upper class, which is the impression that (my interpretation) Greenfield and other writers often perpetuate. He actually likes some of them. But there’s a nuance that is missed, in that Columbo simply wants justice to prevail, rich or poor or middle-class. That justice may not be in a court of law (ex: “Identity Crisis”). But Columbo, the killer, and the viewer all know the exact moment when Columbo has triumphed because we see it in the villain’s reaction to being pantsed by our hero at the close, and that’s the emotional win for us fans. Justice prevails. Roll credits.

I have to say, I enjoy this discussion a whole lot more than debating Columbo’s first name.

I agree that it’s important to distinguish between Columbo the series and Lt. Columbo the character. Lt. Columbo does not have a class bias.

Columbo the series certainly does have a lot of rich people behaving badly. The murder in each episode was often designed to cover up other bad acts, like adultery, fraud, or even another murder. As for the strategy in crafting a villain, obviously the views of Columbo’s creators and writers would be authoritative. I had always assumed that making the villains rich and arrogant wasn’t to create a class contrast with Columbo, but to solve a problem with plotting.

An essential part of the series is the interaction between Columbo and the murderer. There are normally at least three or four face-to-face meetings. Participating in these discussions is clearly not in the best interests of the murderer. So how do you get an intelligent villain to do something completely contrary to his best interests?

The answer is ego. If the villain is too accustomed to praise and deference, he can be blind, until it’s too late, to the threat that Lt Columbo represents. So I’ve always seen the contrast as Columbo’s humility vs the murderer’s inflated sense of self-worth. The wealth difference was only correlation.

If hard-pressed to recommend any references on Columbo, I’d have no doubts: Dawidziak, Koenig and Columbophile.com. The wealth of content and insight given by authors and commenters (in the latter case) is unsurpassed.

Glenn beat me to it about Lilian Mathieu’s 2018 “Columbo : la lutte des classes ce soir à la télé” (“Columbo: Class Struggle on TV Tonight” as translated by Pascal Bataillard), published in English earlier this year by Brill (https://brill.com/view/title/61921).

Anyone interested in my micro-reviews/ramblings about the Berzsenyi and Martin-Jones books [so I’m already starting this post with an iffy assumption] can check the comments portions of the recent “Coolest Cars” piece and 2021 “End of Year Update”.

Both books give shout-outs to The Columbophile Blog, and Berzsenyi even quotes some comments from the Columbophile community. From an academic perspective, the themes and ideas from both books are each very interesting, have definite value and are worthy of intelligent discussion. However, from the perspective of the average reader of The Columbophile Blog, they have definite flaws – but for different reasons.

As CP notes, the Berzsenyi book has simple factual errors that will be off-putting to “Columbo” viewers who will eye-roll at reading that Julie Andrews and not Julie Harris played Carsini’s secretary in “Any Old Port”. Her book is also difficult to read, not necessarily because her analysis is so hard to follow, but because it’s just not smoothly written. High-concept academic topics are challenging enough to consume, and Berzsenyi doesn’t make it any easier with her style.

Conversely, Martin-Jones writes well and presents his ideas in a (generally) clear and lucid manner. That makes his theme interesting to follow, and he has his “Columbo” facts down pat. Unfortunately, he is guilty of trying to shoehorn everything about the show into his overall theory of attention. That’s a shame, because there are several elements of “Columbo” that support his premise. But by reaching for tenuous academic connections when simpler explanations make more sense, he tarnishes his efforts.

But I don’t want to be too negative – each book has great ideas. Brand new is another academic work called “Columbo: Class Struggle on TV Tonight”, by French professor Lilian Mathieu (published late Jan 2022). You can link to the table of contents and first 7 pages, through google books. (Columbo: Class Struggle on TV Tonight – Google Books). The basic theme would appear to be the class issues that are always noted by writers about Columbo, and I’m looking forward to seeing if Mathieu does anything interesting with it. The book is quite pricey for its 80 pages, and I just ordered the last (for now) remaining used copy for $55 through Amazon. I’m afraid that the remaining copies are at least $85, if anyone else has a notion to give it a read.

A few years ago I flipped through “Columbo Under Glass” at a bookstore and thought it was a such an unfocused scatter-shot mix-and-match of ideas and irrelevant “Columbo” lists that it lost my interest. But that was some time ago, and if anyone has strong reasons to recommend it, I am open to reconsidering.

I have the Catz book, I’d recommend it – each aspect of Columbo is deconstructed and (possibly over) analysed. His review of episodes is not in the same league as CP’s but interesting to note where he agrees (mostly) and occasionally disagrees (he ranks Double Shock as a ‘poor’ episode for example!).

How ironic that a book about class struggle would be priced so that only rich people can afford it.

Claude, I’m definitely not rich, just very interested in Columbo!

Thanks Paul. I actually would concur that Double Shock is not a particularly strong episode. Any thoughts from others on Catz are welcome.

It does feature, in my view, the hands-down best performance by a Columbo guest murderer. Martin Landau created two distinct characters brilliantly. According to director Robert Butler, as soon as Landau walked on the set, you could tell from his attitude which twin he was playing. Butler called it a “masterful job.” (https://interviews.televisionacademy.com/interviews/robert-butler?clip=48695#show-clips)

I found the “Paying Attention” book nearly unreadable. Mostly due to what you cited— his propensity to try to shoehorn nearly EVERYTHING into his “paying attention” premise. And the over-abundance of footnote references in the body copy of each chapter made text flow choppily, and much less fun to read. I put it down halfway through and haven’t picked it up since.

Russ, if you had to put down Martin-Jones, you won’t even want to pick up Berzsenyi!

Thanks for all the book recommendations.

“Murder by the Book” has to be one of the best episodes. I like the Columbo mug and doll on top.

Thanks for this. It’s great to have one post, where I can reference all the books and get on with collecting them.

I’ve got ‘…under glass’ and it is very good