Ever wondered how Columbo was able to use phone records to nail the Paris twins in Double Shock, but never definitively pinned Nadia Donner’s hypnosis suicide call on Dr Collier in A Deadly State of Mind?

Likewise, how can phone calls be so pivotal to the story in Murder by the Book, but similar ones in Candidate for Crime fade into the background? If these apparent inconsistencies have vexed thee greatly, you’ll definitely want to dial in to this guest post by Glenn Stewart, a long-time reader and regular contributor to the comments section of this blog.

Glenn has read the extensive and heavily technical vintage phone manuals so you don’t have to! In doing so, he sheds light on how the telephony systems of 70s California worked, and the direct impact those systems had in helping or hindering the good Lieutenant in the course of his investigations.

Without further ado I’ll hand over to Glenn, who has patiently been waiting on hold for several months for this article to appear. Connecting you now, Glenn. Take it away…

I think we can all agree that Columbo is a smart television show. Yes, the character of Lieutenant Columbo is iconic – sharp, subtly devious, humorous, and relatable. And Peter Falk’s superb portrayal of the character imbues him with added warmth, depth, steely resolve, and mischievous charm. But I’ve always felt that the core of the show’s success is in its clever and intelligent plotting, at its best laying out a trail of understated clues that are patiently followed and ultimately paint the murderer into a corner with unassailable evidence.

Results in accomplishing this goal varied, of course, but Columbo’s writing (and I speak of the 70s version) generally had great respect for its audience. For the show to truly resonate with fans over multiple decades, it would have to treat its audience with the same intelligence as Columbo himself and the killers he encountered.

So why do we see such a smart show have seemingly obvious inconsistencies for the audience in its use of telephone records? It’s not that Columbo has never used telephone histories in crime-solving. There are several occasions where he mentions phone records, so we know they exist in his universe. He even uses them to finger the Paris twins in the gotcha of Double Shock.

As anyone who has watched an episode of Law and Order knows, such records can instantly and definitively build a criminal case. But when Jim Ferris calls his wife in Murder by the Book, it’s from Ken Franklin’s cabin. When Dr Collier calls Nadia to cue her death leap in Deadly State of Mind, it’s direct from his apartment. When Dr Mason calls his home to sic the dogs on Charlie in How to Dial a Murder, it’s from his doctor’s exam room. Why isn’t Columbo smartly using those phone accounts to help nail the killer?

For a long time, I thought this was the writers taking advantage of 70s viewers’ lack of sophistication with how phone records could be used. And, of course, several episodes would be much shorter if Columbo got all his answers this way, and not from painstaking clue-gathering. Or, perhaps these were simple oversights from sloppy writers? But Deadly State of Mind was penned by Peter S. Fischer, generally accepted as the show’s best scribe, and Murder by the Book was from the legendary Steven Bochco. These guys weren’t slouches in the plotting department.

Through discussions with fellow Columbophile blog commentators, I was reminded that back in the 70s, many local calls were billed on a flat fee, so records – such as those needed for billing long-distance calls – might be unnecessary, depending on the specific billing plan; and also that pay phones weren’t billed, so their records also may not have been needed.

With these key starting points, I decided to dive into the bowels of Google for more answers. Here’s where I must note that I am not in any way, shape or form an expert or specialist when it comes to telephone records. Consider this post the effort of a dedicated amateur who spent a few hours going down many rabbit-holes pursuing any information on 70s-era California telephone tracking and records. Clarifications, confirmations, or corrections from contemporaneous telephone professionals are welcome.

Fortunately, there are some answers, at least enough to draw some general inferences about Columbo phone records. Spoiler Alert: in most cases (but not all), there is no sloppiness, ignorance, or lack of intelligence on the part of our Lieutenant or the show’s writers. First let’s investigate, then take a closer look at some specific Columbo episodes.

The technical stuff

The most specific information I could find comes from a very dense and technical website that serves as a tribute to the Bell Telephone System. The Bell System (colloquially, “Ma Bell”) served much of the United States until it was ruled a monopoly and broken up in 1982. In California, this was dubbed The Pacific Telegraph and Telephone Company, distinguished, as all Bell systems were, by their blue bell logo.

The site’s “Survey of Telephone Switching” has 13 (!) chapters devoted to telephone switching, whereby “a talking path must be set up between the calling and the called telephone. The method of making this connection, known as switching, has progressed from the simplest of hand operated switches through the more complex manual systems to the present mechanical switching systems.”

With such switching, the Bell system could determine how to bill their customers. Preparing this data was the purpose of Automatic Message Accounting (AMA). “AMA recorded messages presented to the accounting center fall into two main categories; one type of message is charged on the basis of message units and ultimately bulk-billed to the customer, and the other type is itemized individually on the subscriber’s toll statement and referred to as detail-billed messages.”

This is the fancy way of describing that local calls are bulk-billed, and toll (long-distance) calls record the details needed to determine the amount the subscriber will be billed. According to Bell: “For calls that are billed in bulk, it is not necessary to record the office and number of the called subscriber, since the duration of the call and other billing information provided in the call record is sufficient to determine the charge.”

Finally (for our purposes) they note: “As the metropolitan areas grew larger and subscribers began to call regularly beyond their local areas, zone registration was adopted… Although zone registration is an economical method of charging for short calls, it does not leave any record of the details of the various calls.

“For calls requiring more than five message register operations [i.e. longer distances], it has generally been felt desirable to have a record not only of the point to which the call was placed but of the day and time it was made. To secure such a record… an automatic ticketing arrangement was developed. With this system a ticket is automatically printed for each chargeable call, and thus all essential information pertaining to the call is permanently available.”

Los Angeles itself, the setting for almost all Columbo episodes, was served by one area code – 213 (as Ken Franklin helpfully notes in Murder by the Book). According to the McQuilkin College website: “The L.A. area phone calls were based on ‘message units’ according to distance and length of call. A call of less than about 4 miles was local. From 4 to 8 miles counted as 2 message units. Thus a 15-minute call from Westchester to Manhattan Beach was 8 message units, and cost about 32 cents.”

I have found no absolute “scale of message units”, but I would conjecture that there would have been a range where the number of units would increase with longer calls at greater distance. If a call didn’t reach that threshold noted above of 5 message register operations, then there would be no detailed record.

The practical examples

With all the above as our foundation, we can look at specific Columbo episodes through the 70s, examining those times when phone calls could prove crucial to an investigation.

NB – Since we have no way of knowing details of any specific, different phone plans being used by any episode characters, from hereon in we’ll treat all local calls the same – not logged with identifying details.

Ransom for a Dead Man

At her home, Leslie Williams gets the automated ransom call that was set up at her law office. We are shown the machine making the call, but can’t draw any conclusions about the number of digits used in dialling. Columbo knows that the machine was used in the crime but doesn’t look for phone records, so we can assume that Leslie’s office and domicile are not far apart within the same area code.

It should be noted that the actual Bell System Card Dialer Automatic Dialing Telephone, as cutting-edge as it was for the era, cannot itself dial a number at a specific time. However, Leslie is clearly more tech-savvy than she lets on. She expertly rigs a timer and 8-track tape to the device, with a pre-inserted card for her home phone number to allow the “ransom call” to be made without her assistance. Columbo figures this out and does the same thing to her in a demonstration later in the episode.

Murder by the Book

On their way to Ken Franklin’s cabin, he and partner Jim Ferris stop at the small grocery store located nearby. At the pay phone in the back, Ken calls Jim’s wife Joanna long-distance – “operator, a station-to-station call” – claiming to be phoning her from his cabin. The purpose of this becomes clear later on. At the cabin, soon after arrival, Ken convinces Jim to call Joanna to tell her that he’s working late at the office. And Ken knows his phone tricks, because he tells Jim to ditch using the operator and dial direct, or else Joanna will suspect he’s not at his workplace.

This works, and it appears to Joanna that Jim is indeed at the office, and while he’s on the line, Ken guns him down. This sets another series of calls in motion, as Joanna immediately rings the police, then Ken at the cabin.

There’s a lot to digest here. Although writer Bochco has the mechanics of phone call records correct for Ken to establish an alibi with Joanna, it’s those phone call records that theoretically should also blow his alibi with the police. The ruse was to fool Joanna into thinking that Ken was at the cabin at the time that Jim was being killed/kidnapped in his office. Ken knows that long-distance phone records will establish one call from his cabin, and he needs Joanna to verify to the police that this was a call from Ken, and not from Jim.

Franklin arrogantly suggests that Columbo look into this, and the Lieutenant appears to speak with Joanna about it because we later see him tell her: “I told you how he could have done the phone trick.” Joanna doesn’t confirm that Columbo’s right about this, though, so I have to assume that the grocery store and the cabin must be very close to each other. Otherwise, if Joanna is told, for example, “We have a record of a call from Ken’s cabin to you at 2:06”, she would say, “Oh no, Ken called me much earlier than that.” Joanna must not be sure of the exact time of Ken’s grocery-store call. So, Ken’s trickery was successful – to Joanna.

But phone records should have indeed tripped up Franklin (and Bochco). In a Columbophile blog comment of June 26, Rich Weill notes, “He [Columbo] found the record of the call from Franklin’s cabin to the Ferris house. Why didn’t Columbo notice that the time of this call matched the time of Joanna’s call to the police?”

I concur, and this is where Ken’s alibi takes on water. The timing of the calls Joanna made after hearing the gun would almost certainly imply that it was actually at Ken’s place that she heard the murder shot. The police would surely keep, at a minimum, written logs of all their incoming famous-writer-might-be-getting-murdered calls.

And, to add insult to injury, Ken not-so-wisely made sure that Joanna had his cabin number, and so she called Ken right after calling the police – another long-distance record to cross-check, but missed by Columbo. For argument’s sake, I think we can assume that Jim’s office and home are within a few miles in the same area code because there seem to be no phone records used to verify a call from that office to Joanna.

But wait, there’s more! We also have the grocery store call to consider. As an operator-assisted long-distance call, there would presumably be another record for Columbo to check. As Richard explains, “Finding the record of Ken’s call to Joanna from the grocery store initially might have been more difficult (as the phone company might not have been able to search by recipient, only by sender, at the time), but once Lilly LaSanka entered Columbo’s investigation, that was possible, too.”

Although I’m not a fan of using phone records for gotchas, it might have worked in this instance to bolster the circumstantial case Columbo has made (with the identical murder plan found in Jim’s old notes). Ken wanted to establish an alibi, but the very phone records he used to do that should also have done him in at the moment that Joanna made her subsequent calls.

The Most Crucial Game

The episode hinges on an alibi phone call that Paul Hanlon claims he made from his stadium skybox, but was in actuality made from a phone booth nearby Eric Wagner’s mansion. I have been screaming, “Columbo, check the phone records!” for years on this one. However, I was wrong. At the show’s start, we see Hanlon make his first call to Wagner to wake him up. Clearly and deliberately, only seven digits are punched – a local call, and if within those 5 “message units”, no detailed records. But why didn’t the Lieutenant check records of phone booths near Wagner’s place?

The closest answer I could get came from a 1993 article in the Chicago Tribune. “There are two types of pay phone technology currently being used in the industry, that used by Illinois Bell pay phones and that used by non-Bell pay phones. On Illinois Bell pay phones, calls paid by inserting coins are not recorded and cannot be traced. However, coin calls on non-Bell pay phones create the same call record of the date, time, duration and receiver of the telephone call as any other home or business phone. Any drug dealer or other criminal seeking to use non-Bell pay phones for the purpose of anonymity is unwittingly providing law enforcement authorities with a readily accessible record of his/her transaction.”

Obviously, we can only try extrapolating this to 70s California, and it may not be accurate. But in the episode, we see that Hanlon is indeed using a booth with a Bell logo.

Double Shock

Here, phone records are used by Columbo to establish that the Paris brothers have lied about not speaking to each other. We can therefore assume that Dexter and Norman lived far enough apart to establish that they’ve talked to each other “about 20 times in the last 10 days”.

The use of phone records here is, however, not very satisfying, as it doesn’t establish what they talked about, comes from out of nowhere by Columbo, and feels like a cheat used by the writer to quickly wrap up the story threads.

Lovely But Lethal

Moments before Viveca Scott puts chemist Karl Lessing’s skull under the microscope, she appears to make a phone call to her “personal friend” the police chief, so she can report the totally commonplace wrinkle-free-miracle-beauty-cream-formula theft. I’m convinced that this is a feint to try to scare Karl into giving up the precious recipe. Viveca angrily bangs the phone down when Karl calls her bluff while she fakes waiting for the chief to come to the line.

Candidate For Crime

After offing his campaign manager, Nelson Hayward goes back to his place, where he muffles the phone and calls the police to report the crime. This is a seven-digit number, feasible to avoid call specifics. One could speculate that for all calls to the police, local or otherwise, it would make sense to have a system that would automatically establish all the details, but I could find no information about the auto logging of phone records for incoming police calls, and we can’t simply assume this was possible in that era.

Also note that Columbo specifically mentions that any call from Hayward’s beach house would have been a long-distance call with a phone company record attached. No record, no call from the murder scene by the phantom “mob killer”.

Double Exposure

Mr (sorry, Dr) Kepple rings up Mrs Norris and, using the expertly nuanced skills of a highly-trained vocal impersonator and mimic, tries to implicate her in the killing of her husband. He dials 7 numbers, so you could assume it’s a local call. But you might also wonder how Norris’s sprawling suburban mansion is within local calling distance of downtown LA…”

An Exercise in Fatality

Milo Janus simulates a call to his home from Gene Stafford. Janus claims that the call is from Gene’s gym, when in reality it originates from Janus’ home study. No records would be associated with either element of this, as long as the gym and Milo’s home are close enough to each other. However, given that Gene’s franchise was in Chatsworth and Milo lived near the beach (at least 16 miles away), this seems a bit of a stretch.

Deadly State of Mind

Dr Collier punches up a 7-digit number to reach Nadia, so this could theoretically be an untrackable call. Of course, the real chutzpah is Collier making the call while standing about 15 feet away from Columbo! The Lieutenant later accuses Collier of making the fatal phoning after Nadia’s receiver was found off the hook following her death, but there seems to be no actual proof.

Old Fashioned Murder

Columbo is investigating a voicemail call, faking a shooting, left by Milton Schaeffer for his brother. The call was made from a city phone booth (not Bell), but the Lieutenant explicitly says: “We don’t know where the call came from, and we’re trying to track it down.”

How to Dial a Murder

We never actually see Dr Mason ring up the entire number to his home from his doctor’s exam room to sic his dogs on poor Dr Hunter, so we’ll have to assume that they are in close enough proximity. Columbo’s work-around – looking at Mason’s chart spike while hooked up to the heart machine – will have to do.

To conclude

In summary, it is quite easy for present-day Columbo watchers to see the show through a 2020s prism, taking for granted our now-commonplace technological efficiencies. We could easily assume these tech efficiencies to be part of the earlier era, particularly since Columbo himself touts the existence of phone records at several points in the 70s.

Scouring the available evidence, it would appear that the show did indeed generally follow the rules when using phone records. Or perhaps we should just say that it was very convenient that the show’s killers and victims and offices often wound up close enough to each other to make sure phone records wouldn’t end a Columbo 45 minutes too early. That would have been the real crime.

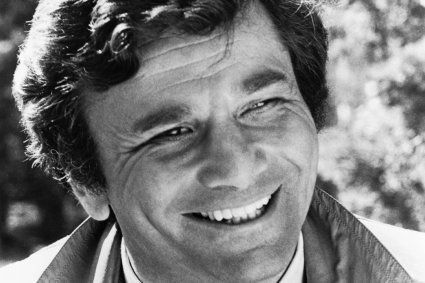

Glenn Stewart spent 25 years in the music radio business across the United States specializing in classic rock. For the past 15 years he has been working in History, English and education assessment in the juvenile justice system. He has also taught ‘Issues In Media Industries’ as adjunct faculty at a New England university. His favorite pre-1980 TV rewatchables are Columbo, Mission: Impossible, Batman, The Prisoner, and The Twilight Zone.

Well folks, if you’re anything like me you’ll have found this article highly educational and enlightening. My sincere thanks to Glenn for his diligent research and for shining a spotlight on some of the series’ pivotal phone shenanigans. If any of you would like clarification on any examples not given in this article, shout out to Glenn in the comments section below and I’m sure he’ll be happy to provide some insight.

It’s been lovely chatting, but it’s now time to say farewell. I’ll see you around. Are you still there…? I’m not going to hang up first! No, you hang up first…

Digressing slightly but I completely agree with your view about the core of the show’s success being the plotting and sleuthing. I also like the way Columbo analyses the crime scene which is made easier for the viewer when he is given the opportunity to think out aloud, eg. to Sgt Wilson in ‘now you see him’. Whilst everyone there says ‘it could have been anyone’ Columbo has narrowed things down in minutes after diligently recreating the murder from the scene. His gentle ‘hypothesis testing’ with suspects is also masterful. As one suspect deduced “you pass yourself like a puppy dog digging holes in the garden…but you’re laying a mine field…and wagging your tail”. My favourite ‘hypothesis testing’ scene is where he says “I knew you could do it” to the great Santini. Wonderful.

I don’t know if this is intentional, but IMO Columbo’s method is to first eliminate the obvious. Example: the lipstick smear in TW. He also watches people’s reactions. Especially when he says somebody was killed. Again Lloyd was the best example. As if Columbo suspects that, that kind of an emotion is pretty hard to fake. Because of his experience with human nature. He also factors in how people think. There was an episode where the decease wouldn’t have put on his/her shoes in a certain way. Or maybe it had to do with the underwear. Maybe it was a label thing. So he tries to think like both the suspect AND the victim. He also tries to link-up clues. If he finds more than one instance of what’s he’s already suspected, then that usually seals the deal. And then he spends the rest of the time trying to trick the suspect into getting caught, so the crime can be proven. It’s actually pretty formulaic. And I think the Production had fun with figuring out as many ways as they could to keep the formula fresh and intriguing. That’s probably the real genius of the series. But as much as is obvious, the viewer never gets totally inside Columbo’s head. All we can do is apply our own guesses as to what we’re watching. It’s like a dual layer of sleuthing is constantly going on!

While combing through antiquated technical phone manuals for this piece last year, I also spent some time researching the very real psychology that Columbo uses in his very fictional investigations.

Angelo, I agree 100% with your observation about “hypothesis testing”. That phrase covers a questioning tactic that Columbo uses, “deploying discrepancies”, which arise from a statistical model social scientists formally call Posterior Predictive Checks. In highfalutin jargon: “simulating replicated data under the fitted model and then comparing these to the observed data”. More simply, its that feeling Columbo gets in his gut when the “little things” don’t fit the crime theory, creating the discrepancies that he uses to unnerve the killer in those seemingly casual chit chats.

Understanding the psychology being used by our favorite detective puts a fresh spin on repeated episode viewings. It’s also one of the few elements of Classic Columbo that they (sometimes) got right in New Columbo.

Re Candidate for Crime: while amusing watching our Detective faff about in the tow truck while timing how long it takes to drive from A to B to make the apres murder phone call – couldn’t that call have come from someone other than the murderer? Say the people who had been doing the threatening?

Mafiosa, mafiosa, mafiosa boss sends out killer, expects the job to be done and rings on the assumption, saying, see, told you so. That call didn’t necessarily have to have come from the guy who did the bumping off.

One big problem with phone records that troubles me is not the 70’s Columbos’ but the great “Butterfly in shades of gray” from the 90’s. Fielding Chase makes a call from his car phone to establish his alibi which Columbo eventually manages to break proving that there is no service at the place where Fielding claims he made the call. But cell company records should have made all this unnecessary right away, allowing Columbo not only to prove that Fielding lied about the place he made the call from but establish the actual place of the call, putting him right near the victim’s home, i.e. the case should have been solved in five minutes.

And the show is obviously aware of the fact that car phone call could help establish exact whereabouts of a person making it. In “Murder of a rock star” before Hugh Creighton reveals his speed trap camera alibi Columbo asks him if he made any calls on his car phone.

I didn’t dig into 90s cellphone tech in my original piece, so I did some Bonus Research to hopefully address your issue.

“Murder of a Rock Star” was in 1991, and if cell phone records could indeed establish location back then, it would back up your point about 1994’s “Butterfly”. But Columbo is not looking to determine the exact spot where Creighton was calling from, only that he was calling from his car. I’ll admit that’s an inference on my part, because Columbo begins to state, “Phone records could – ” and gets interrupted by a scene-stealing DA. But Creighton never tries to use a specific location as an alibi, only that he was driving at the time. And since Creighton didn’t make any calls, he can’t verify that he was in his car to make them.

I don’t believe Columbo could establish exact location in 1991, nor in “Butterfly”. That ep was shown in January of 1994, so it was made in 1993. Today, cell calls are tracked precisely with GPS, a digital “pinging” process. But back then, minus GPS technology, it would have been tracked using the analog method of triangulation. This uses the phone’s proximity to cell tower locations to calculate where a call would be coming from. In areas with more towers, closer together, this process becomes more reliable. But as with much technology in the TV universe, it sounds a lot more accurate than it actually is in practice. I’ll reference here a 2014 New Yorker article noting that even 20 years after “Butterfly”, this was far from the exact forensic science it appeared to be. So back in 1993, I can only imagine how sketchy it was. (What Your Cell Phone Can’t Tell the Police | The New Yorker).

But Fielding Chase calls 911….wouldn’t there be a record of that exact location in a 911 call? Actually, no. It wasn’t until 1994 that the FCC ordered wireless carriers to find ways for emergency services to locate mobile 911 callers. In a comment below about 70s phone records, I noted the origins of the E911 system that would track locations – but that looks to have been for land lines only.

Chase claims that he was at his home about 30 minutes away from the murder when he “heard” Gerry getting gunned down, immediately getting into his car to (supposedly) race to the scene, when he called 911. Was triangulation used extensively in 1993, and if so, would it have been able to place Chase substantially closer to the murder scene than to his own home? That’s debatable, and here’s where I fall back to giving the writers (and, by extension, Columbo) the benefit of the doubt unless we see overtly contrary evidence. And since Peter S. Fischer was an experienced Columbo scribe, I’ll roll with the premise and assume that since the whole gotcha depends on cell technology, Fischer did his own research and had contemporaneous experience with what was possible in 1993.

Great article, and a topic that has been bothering me for a while with the episodes. Some other thoughts regarding phones:

Suitable for Framing: There should have been a record of the call when Tracy calls Dale at the studio. Unless of course they were close by…

Publish or Perish: How did Riley Greenleaf make all these arrangements with Eddie Cane without a trace of a call? I guess Riley’s mansion and his office were close to Eddie’s apartment over the garage…

Negative Reaction: There must have been a good number of calls between Paul Galesko and Alvin Deschler before the day of the murder. I guess the Galesko mansion and his office were close to where Deschler lived…

Identity Crisis: How did Nelson Brenner call “AJ Henderson” without a trace? I guess the hotel was close to the Brenner’s office. Or maybe he had special CIA phone lines?

Thanx, Test….Tracy calls Dale using a 7-digit number, so that’s local, and while we see AJ Henderson pick up the “Steinmetz” call at his hotel, we actually don’t know where Brenner was calling from, so we can’t make any assumptions.

We see Greenleaf getting together with Eddie at the junkyard watching stuff get blowed up real good, and Galesko meets Deschler at a lakeside spot “near Palmdale”. Without any dialogue to tell us those were first-time meetings, I’m quite comfortable pegging those as regular let’s-make-our-plans locations, used instead of telephoning.

After digging into the Bell archives, my general rule of thumb now is to give the writers (and, by extension, Columbo) the benefit of the doubt unless we see overtly contrary evidence. For example, the distance from Gene’s gym to Milo’s beach pad in “Exercise” seems a tad suspicious, but isn’t screamingly obvious and certainly doesn’t get in the way of my enjoyment of the episode.

A deadly state of mind is the one that really troubles me , im no communocations expert and never lived in the states let alone was i born in the 70 s but dr collier

Makes it clear to columbo he can never prove nadia was killed by a telephone call despite making the call right in front of columbo

And abkut 4 others , surley they would have at least a time window to work on and i remember collier says we couldspeculate all day wouldnt mean a damn thing when surely it could have been linked to the call

This dosent sit right with me

I mean he made the call right in front of columbo seems a bit of a leap to me

My apologies to commenters who had been hanging in “Awaiting Approval” limbo for a few days on this thread. I think the issue’s been resolved and we are now up to speed with your (excellent) thoughts on this topic!

You out did yourself CP. what a great article. I’ve briefly thought about the phone records during various episodes but didn’t really think about it in detail. I’m 59 years old and live in the states and can remember in the early to mid 70’s our house receiving many hang up calls for several months straight, my parents finally had to call the phone company so obviously the calls weren’t recorded back then and it wasn’t until the early 80’s that things like caller ID came out. I do wonder about Hayward calling the Police, you would think they had a special service even back then. Anyway great work.

For those of you itching for more thrilling phone-related technical minutiae……

I did catch an LAPD telephone reference after my essay went to print with CP. In “Negative Reaction”, Columbo tells Paul Galesko: “Your phone call was received at police headquarters at 5:45. That’s recorded.” That word “recorded” would probably be interpreted today as being electronically recorded with its originating telephone location. But was that the case in 1974, or was it simply “recorded” by hand? Or, was this merely recorded via answering machine without the capacity to trace the number? I noted in my essay, “I could find no information about the automatic logging of phone records for incoming police calls.” I did, however, find some tangential details that I edited out of my final piece for length and clarity. Although not directly about LAPD telephone calls, the evolution of the 911 Emergency System points toward some tentative speculation.

The first 911 call was publicly demonstrated in Haleyville Alabama in 1968. But this was just B911 – Basic 911. “As B911 service became more widely established across the country in the early 1970s, 911 call takers began to see the value of having automatic access to the name, address and phone number of the emergency caller instead of relying on the caller, who was often not able to provide that information during the call….This led to the establishment of Enhanced 911 (E911) services in the mid 1970s that originally included automatic location information (ALI) and automatic number identification (ANI).” (iCERT-9EF_Historyof911_WebVersion.pdf (ng911institute.org)

In 1976, Chicago became the first city to utilize E911. In 1978, Alameda County, across the bay from San Francisco, became the first California area to use it, but only with ANI, and not the all-important caller location. So, not only was E911 not really widespread enough to impact Columbo, it was also too late for Karl Malden to use it to track Alameda crime calls on “The Streets of San Francisco”. (Emergency Services Office of E-911 – History of 911 (countyofunion.org)

Just finished watching a Nov. 1977 Rockford Files ep (“Irving The Explainer”) in which Rockford comes to the aid of a man in his apartment who’s been shot in the stomach. “Hold on, I’ll call an ambulance”, which Jim proceeds to do (presumably at a hospital), then gets an answering machine and actually has to wait until someone responds. Later in the episode, a man has a heart attack and we hear “Call an ambulance!” once again. Nope, no 911 in Malibu.

What a great post! The problem if the timing of the phone calls in Murder by the Book is something I have commented on in the past. (A lot of people have.) It really should have broken Ken Franklin’s alibi. I grew up in the seventies and used a rotary-dial phone until I left home. The rule back then, as I recall, was that your phone bill noted the time and duration of all toll calls. Local calls were covered in your base rate. You could make as many as you liked, and no records were kept.

As for the handkerchief-over-the-receiver gag: the silliest instance has to be The Greenhouse Jungle. Ray Milland was such a snarling caricature, I can’t understand why Susan didn’t just say, “Jarvis, quit messing around” the instant she heard his voice.

Great article! And thanks for something of a trip down memory lane re old phones and the quirks of local vs long-distance.

Loved the comments under the pictures too. “Heyward’s magic hankie…” made me think that no one would also fail to immediately recognize Jarvis Goodland’s voice, hankie or not. One of the best bits of a rather campy episode.

What a terrific article and thanks to Glenn for all the technical research. As a retired telecomms engineer I always wondered about this not being familiar with the US phone systems. Here in the UK back in the 70s before we went digital, electro-mechanical counters were used to bill subscribers, the counter would increment when it received pulses the intervals of which were set by the destination number called and time of day (a morning call was generally charged at a higher rate than an afternoon call which cost more than an evening call), a long distance call resulted in more pulses than say a local call. The bill was calculated based on the difference in counter readings. So the exchange actually had no record of called numbers, just a counter reading. Unless a call was made by an operator who kept a record there really wasn’t much for the police to go on.

Ray, thanks for the feedback on UK phone systems. I have to admit that if there was an important phone call in “Dagger of the Mind” to research, I was definitely not eager to scurry down the UK Telephone Systems rabbit-hole!

The still you used for Candidate for Crime reminded me of the rag over the phone gag that has no basis in reality but in this episode it was successful in disguising his voice to a laughable degree. A gag later spoofed on Police Squad with Leslie Nielsen where the rag disguises his voice as a woman!

Hullo from NE Victoria, Australia.

I never once bothered to think about this subject. Reason is, I always knew American phone systems were a bit loony.

I also remember Australia’s phones when one needed to connect with an operator.

So, interesting and educational as I found the post it was a subject I let slip by.

Thanks tho. Cheers

What a marvelous idea for a research project, and studiously accomplished! You’ve answered many of my own long held questions on the subject. Thank you so much for sharing your efforts. (Murder By the Book is a very entertaining, atmospheric show with great performances, but Steven Bochco has said many times that he had no experience or natural gift for mystery plotting; the plot of that one is never going to bear close scrutiny.)

Thank you, Glenn, it’s very interesting.

Telephone is a very important element in the Columbo-episodes, and it shows that nowadays episodes would be completely different, if not impossible.

Another important use of telephones is the way Columbo uses them, calling someone, or being called, in the presence of the suspect. Columbo wants the suspect to know something, and that’s why he calls or is called. With nowadays telephones, this would be impossible, or at least very difficult.

(In Butterfly in Shades of Grey, 1994, Columbo is mocking the modern telephone-technology, holding his hand near his ear, without having a phone in it.)

The pre-cellphone era made for a good excuse to have Columbo reached on a suspect’s telephone. I would add that the invasion of the killer’s personal privacy – having Columbo use the suspect’s own land line – is an added bonus that through the years we’ll find the psychologically-savvy Columbo often taking advantage of.

If Columbo were rebooted for the 2020s, the one major change I would make to the character would be to have our lieutenant be a bit of a tech nerd. In this way, he can use his smarts to have technology trip up the crooks in a way the viewer can understand. Keeping the Columbo character dense about technology in this era would be very off-putting and unrealistic.

He’d definitely have to be a tech nerd. But of course he’d play himself as being a bit dense about it anyway.

Yes! I’ve said this before, having a detective be clueless about tech would be completely unrealistic in the 2020s. It would make more sense to have him throw off the suspects by rambling on about random tech stuff, or playing Pokémon GO in their living rooms.

Thank you for digging into this! As a 25+ year USA phone company veteran with a billing background – the inconsistencies always irked me. The tricky part with incoming calls of all kinds (especially wireless) is that you need to find the source which initiated the call to determine length/distance. In the 1970’s there wasn’t much a way to search “who dialed this number” of the millions of local and LD calls placed daily. It’s also important to distinguish that landline phone carriers also did not have zero-rated billing. They did have records of phone calls (local and LD) which would display on the bill for rating purposes. What they lacked was a real-time means to query or search that content on demand.

Such functions have been available since the 1990s based on the CALEA act. CALEA requires that telecommunications carriers and manufacturers of telecommunications equipment design their equipment, facilities, and services to ensure that they have the necessary surveillance capabilities to comply with legal requests for information. Communications services and facilities utilizing Circuit Mode equipment, packet mode equipment, facilities-based broadband Internet access providers and providers of interconnected Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) service are all subject to CALEA. These compliance requirements include wireless services, routing and soft switched services, and internet-based telecommunications present in applications used by telecommunications devices.

Gwen, it sounds like I could have used you as a research partner!

Glad to help dig in if needed !

I wish more of our favorite rewatchable series delved into the details like Mr. Stewart has, (focusing on the phone system. Living in California I do remember the detailed customer invoices. People would review every phone number to make sure it was recognized. Once in awhile it wasn’t. Also on our same invoice there was local and long-distance carrier billing. At the time “Pac Bell” and “AT&T.” People also waited until “after hour” rates to save money making long distance calls! And yes (in our market) there was free calling to anyone in which you shared the same area code. But would be charged the minute you called a different area code, even if (by freak chance) it was only a block or two away. Now that it’s been mentioned, yes message units applied. Deregulation of the phone monopolies was the first step in simplifying everything, and eventually (a long eventually) made the system economical. And imagine (everyone) how most of all this was done without the convenience of today’s “computers!”

GREAT article, thank you so much Glenn Stewart!!

Thank you for the kind words, Mr. Sun (Ms. Sun?)

I certainly learned a lot about the super-duper-exciting world of Automatic Message Accounting, Zone Usage Measurement, Direct Distance Dialing, call identity indexers, message unit calculation, assembler-computer output tapes, and Electronic Switching Systems. Like much research, it can be a pain in the butt, but also rewarding when you find the answers you need.

OMG I remember those “after hour” rates now that you mention them! How funny!! It’s akin to talking about the Edsel or the Studebaker now.

Have to admit that, inspired by Robert Culp, I once resolved to deal with nuisance telephone callers and scammers by adopting a stupid voice and pretending to be a moron. I suppose this falls under the category of what used to be called “playing the fool” ! I don’t know why I’m telling you this, I just thought it would help to talk to someone.

This element of Columbo has always intrigued me as some of the phone calls and the ‘checking of records’ has sometimes confused me in their apparent contradiction. However this is because I’m in the UK, watching some 40+ years later, our logging systems (presumably) differ and I have no understanding of how calls are connected and logged in the US. A very informative article, not just on the Columbo front but generally in US telephony.

ROSEBUD! The FATAL word repeated twice for Laurel and Hardy…grrr, grr!

Hello! Interesting post- yes, the use of the phone was a key factor in many Columbo episodes- Leslie in Ransom is a big fan of the phone and its cool gadgets! We even see stepdaughter Margaret using the phone- “Police Department? I like to speak to Lieutenant Columbo.” How phones have changed in the last 50 years! – I’m writing this reply from an IPhone….

Speaking of Ransom- in 8 days it will the 50th anniversary that the episode premiered on NBC- March 1st- 1971-2021- time flies. Such an awesome episode…. I saw it for the first time like in 1980…. was 2 when it premiered in 71’….. Only Lee Grant and John Fink are still with us, alive…. Peter Falk passed away in 2011 (83) and Pattye Mattick in 2003, at only 52…. 😞

My 2 cents, be well, be safe, everyone….

Ed from Florida

I want to make sure to thank CP for generously affording me the opportunity to contribute to his blog space. Columbophile is his baby, and I feel privileged to have been allowed to do some babysitting for him this week.

Also, thanks CP for captioning me with my secret adolescent Columbo crush Arlene Martell!

Phone calls in “Columbo” always bothered me, so you did a great job, Glenn, illuminating the subject! Especially how you put the finger on the flaws of “Murder by the Book”, a case which was always far from excellent in my book.

Full credit to Columbo expert Richard Weill for the original catch on Murder By The Book. All I really did was use the expanded blog space of the article to provide the specific details on what Ken was trying to accomplish and the timeline that could have/should have been used to nail him later.

Columbo then could have tested out that classic line he later uses with Milo Janus: “You tried to contrive the perfect alibi, sir. And it’s your perfect alibi that’s gonna hang you.”

Thanks, Glenn. The irony here is that, despite this flaw, “Murder by the Book” remains my all-time favorite Columbo.

Glenn is another Columbo fan who indulges in creating Columbo stories of his own. His stories are meticulously plotted with lots of detailed clues. (My own efforts in this direction — I’ve now written four scripts for my “Det. Columbo, NYPD” prequel idea — tend toward more thematic clues rooted in the milieu in which the story is set.) So it was no surprise at all to read Glenn’s deep dive into this thorny area. Glenn is all about the details.

Long-distance phone records (specifically from the South Central Bell Telephone Company) also played a part in “The Bye Bye Sky High IQ Murder Case,” as it was the precise time and duration of Miss Eisenbach’s call with her father in Memphis that provided Columbo with a timeframe matching the cuing on the turntable.

I’m a bit embarrassed to admit that I totally forgot about the phoner in “TBBSHIQMC”. Yes, Los Angeles to Memphis….they’d have a traceable record on that one!

Hopefully, the rights to the “Columbo” property will get resolved soon, and someone will be smart enough to take Richard up on his prequel script, which is quite good. If a prequel series ever happens, Rich, you know who you can reach out to for a couple crime-clue ideas!

Hey, any interest in tackling the “Rockford Files” next!?

Oh sorry, just thinking of the show’s introduction that starts with Rockford’s answering machine! LOL!!

The dictaphone answering machines seen in Rockfords opening credits are like gold dust now, snapped up by Rockford enthusiasts for hundreds of dollars! The phone is a 2500 in black, easily found on eBay and will work with the modern system ( provided it’s a working example that is!)

Ahhh yes the lovely “chameleon” like actress Arlene Martel (albeit with the aliases on her name as well). Met her once, very gentle and sweet! Equally beautiful!

But I’m more fascinated by the photo of Columbo with Charlie Clay in a slight and apparent lovefest!!!

…..Arlene Martel, Vera Miles, Anne Francis, Lee Grant, Suzanne Pleshette, Pat Crowley, Honor Blackman, Nita Talbot, Joyce Jillson, Tisha Sterling, Mariette Hartley, Jessica Walter, Gretchen Corbette, Joanna Cameron, Poupee Bocar, Gena Roland, Lesley Anne Warren, Karen Machon, Anitra Ford, Anjanette Comer, Janet Leigh, Barbara Rhodes, Cynthia Sikes, Diane Baker, Lola Albright, Kim Cattrall, Janice Paige,….ooh, lah, lah….The only lovely lass from that era that wasn’t in a Columbo is my favorite: Susan Oliver.

Only a handful of these ladies are still with us. To the others, RIP……

Great job, Glenn!

Thank you….Just last night I saw my crush Arlene on an episode of “Wild Wild West”, where of course she had to get a smooch from Milo Janus.

One should mention the phones, virtually all the pictures and examples show variants of a design by Henry Dreyfuss. He came up with a brand new approach to telephone design by which all the components were fixed to the metal base plate and the cover simply slotted over the top. Previous designs used the shell as a structure to mount everything to. This meant that, at will, the colour of any given set could be changed by simply switching the shell, handset and cords, which gave rise to a plethora of colour options, any colour other than black carried a higher rental fee, it was opulent to have a coloured phone. The design also had a handle at the back and a long line cord so you could walk around with the phone – previously unthinkable.

There is no straight line in the design, every line is a curve, which gives comfort, strength and visual appeal – legend has it that the curve of the handset is based on the average radius of the curve of the back of a womans leg!

When they died the phones didn’t get binned, they went back to the factory for re-furbishment, polishing and re-issue. In the 80’s, when black was back in vogue and the phone companies had huge inventories of pastel pink and blue they sprayed thousands in black to get them back in service.

The design was produced, identically, by several companies, serving different phone operators. California was covered by Bell System and therefore columbo’s phones would have been made by Western Electric.

Interestinly columbo showcased several new designs over the years. Ransom for a Dead Man features the very high tech card dialler phone, which would have been a new product at the time, and Old Fashioned Murder features a Western Electric Automatic Telephone in a less prominent role.

I have to wonder whether the ad breaks for the original screening carried Bell System adverts for the latest products.

Along with IBMs typewriters, Dreyfuss designed phones must be one of Columbo’s most commonly occouring tech themes!

I’m not a massive fan of Double Shock, or in fact anything involving identical twins. But I thought Columbo didn’t need to know the content of the calls, as just their existence was enough to convince him that firstly the twins had both lied, and also that they were probably complicit.

.

The sheer number of calls would be very suspicious, particularly after the denial. But it wouldn’t be enough. The “smoking gun” was the fuse replacement time. And the damp towel.

Not a fan of anything with identical twins! LOL Thanks for the laugh — not sure why that struck me as so funny, but it did!

Oh yeah, but double doses of Martin Landau? What could be more fun!?!

Joanna Clay! In Last Salute to the Commodore- “Daddy!”….😮a classic..