Almost a year to the day after the dismal Undercover aired, Lieutenant Columbo was back in business – and this time he brought Norm from Cheers along for the ride.

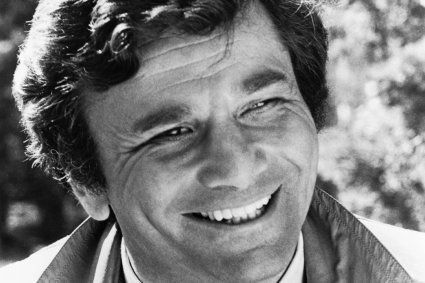

Starring man mountain George Wendt as an unlikely double killer and Oscar-winning actor Rod Steiger as a menacing mob boss, Strange Bedfellows burst onto screens on May 8, 1995.

Can it be as comforting an experience as entering a bar where everybody knows your name? Or are we at the stage in Columbo’s screen career where we fear the worst every time a new episode rears its head? It’s time to place your bets and find out…

Dramatis personae

Lieutenant Columbo: Peter Falk

Graham McVeigh: George Wendt

Vincenzo Fortelli: Rod Steiger

Teddy McVeigh: Jeff Yagher

Bruno Romano: Jay Acovone

Sergeant Phil Brindle: Bruce Kirby

Rudy: Don Calfa

Lorraine: Linda Behringer

Tiffany: Karen Mayo-Chandler

Barney: John Finnegan

Directed by: Vince McEveety

Written by: Peter S. Fischer (as Lawrence Vail)

Score by: Dick DeBenedictis

Episode synopsis

Gargantuan race horse breeder Graham McVeigh would be living his best life if it weren’t for his pesky, wastrel of a baby brother, Teddy. The floppy-haired cool cat has racked up gambling debts in the region of $200,000 and big Graham is sick of picking up the tab.

Help appears to be at hand in the svelte form of Graham’s racehorse Fiddling Bull, who has been deliberately held back so his secret stunning form can see him romp to an unexpected victory in some big money race. If the horse – a long shot at 20-1 odds – can secure the victory, Teddy’s inside information to his gambling den pals can wipe his debt clean. HURRAH!

Graham, however, wants a more radical approach to dealing with his troublesome brother. On race day, he dopes his own horse, leading it to sink without trace in the big race. Devastated, Teddy now fears his very life is in danger from the shadowy Bruno Romano, a restaurateur and bookmaker with mob connections, who very much wants to call in the bloated debt.

Playing Teddy like a fiddle, Graham claims he will speak to Romano on his brother’s behalf and clear as much of the debt as he is able. He will do nothing of the kind. Instead, he dons a comedy beard and hat and creates a commotion at Romano’s restaurant, freeing a mouse in the ladies’ bathroom and using the diversion created by a screaming patron to sneak into Romano’s office and phone home to speak to Teddy. He offers his brother reassurances that all is well, but is really establishing a phone link between Romano and Teddy that will tie into his overarching, murderous scheme.

As Romano and co. continue to fret about the rodent incursion, Graham makes good his escape and returns home to Teddy. He spins a cock-and-bull story about how they need to head out to a secluded roadside location to meet Romano and hand over a cash payment. Trusting Teddy agrees, and the pair split in the younger brother’s car.

Upon reaching the supposed rendezvous point, Graham gets out to ‘stretch his legs’, but actually slips a gun out of the cash bag (which he bought earlier at a pawn shop) and approaches Teddy’s driver side window. Pretending to have seen a flicker of car lights approaching, Graham fools Teddy into sticking his head out of the window, at which point big brother blows him away! Remembering to wipe his prints off the car doors and interior, Graham even has the presence of mind to remove a tell-tale cigarette butt from an ashtray before tootling off on a ridiculously undersized fold-up bike he’d stashed in the trunk.

The next morning, Teddy’s body is found and a decidedly poorly Lieutenant Columbo is amongst the detectives sent to investigate. Poor Columbo has had a bad experience with clams the night before (reading between the lines, he’s definitely spent all night sitting on the porcelain throne) and is in a wretched state, but, true to form, that doesn’t stop him noticing things the other cops miss.

Frisking the corpse, Columbo finds betting receipts in Teddy’s wallet. Even more interestingly, there’s a receipt for a deluxe car cleaning job that was carried out at lunch time the day before. The snooping sleuth then discovers ash in the car ashtray, which is sent off for analysis. Swigging pepto-bismol by the litre, Columbo then makes a beeline for the McVeigh horse stables to break the bad news to Graham.

Immediately upon their meeting, McVeigh lights a cigarette before spilling the beans about Teddy’s gambling debts and the certainty that he was executed for welching on said debts. He claims that Teddy received a phone call at approx. 8.30pm the night before from a man named Bruno, which caused the younger man great angst. Three hours later, McVeigh tells Columbo he heard Teddy leave the house and drive away. When he was still gone in the morning, he feared the worst and called the LAPD.

The thrill of the chase appears to help Columbo overcome his tummy ache. He even bums a smoke off McVeigh in the first example of the Lieutenant sucking on a cigarette rather than a cigar in the series’ long history. He then effortlessly inveigles McVeigh into revealing that his brother didn’t himself smoke, giving the detective some decisive intel very early in the investigation.

Left to his own devices, McVeigh puts part 2 of his plan into action. He rings Bruno Romano and says he’s willing to pay off Teddy’s debts in order to safeguard his own future. If Romano will meet him at the horse farm that night, he’ll hand over the loot. Romano duly agrees, and turns up, armed, under cover of darkness. When he’s inspecting the cash, however, McVeigh takes the upper hand, whipping out a large calibre revolver and busting a cap in his foe’s chest.

Romano goes down face first on the rug, and for the piece de resistance, McVeigh takes the gun he used to kill Teddy and places it in the dead man’s hand. He takes Romano’s own gun and safely squirrels it away before calling the police to report the beastly incident. Columbo is once again in the working detail and knowingly remarks about how fortunate it was that McVeigh was able to get to his own gun in time to use it first against such a dangerous man as Bruno Romano – no doubt the same Bruno who phoned to speak to Teddy the night before.

As is typical of his investigative style, Columbo drops a bombshell on McVeigh before he departs. He reveals that he found the car cleaning receipt in Teddy’s wallet, and that the ashes found in it came from the same brand of cigarette that McVeigh himself smokes. How can that be if McVeigh wasn’t in the car with Teddy at any stage that day, as he claims? Certainly someone other than Teddy was in the car with him at some point after it was given a thorough cleaning. And that person just happened to have puffed on McVeigh’s preferred choice of smoke. That’s quite a coincidence…

Widening his search, Columbo visits Romano’s restaurant the following day where he speaks to cynical waitress Lorraine. She casts major doubt on Romano’s involvement in the killing of Teddy by claiming she was in the sack with him at the time he was allegedly out committing murder. Even if the ballistics of his gun match the one used to kill Teddy, Romano cannot have been the one who fired it. She can’t disprove, however, whether Romano made a menacing call to Teddy from his office phone.

As Columbo mulls this over, he overhears the restaurant barman braying down the phone to a pest control company. Two weeks ago, they had been in to secure the premises against rodent incursion. Why, then, were there two mice in the ladies’ bathroom two nights ago? Intrigued, Columbo goes so far as to rummage in the bins to find the corpse of one of the mice. It’s a rather large, unusual-looking specimen, which you can bet the house will have a material bearing on his investigation.

Shortly after this, the Lieutenant is abducted by two hoods and packed into the back of a black limo. He is taken to the palatial beach-front dwelling of mob boss Vincenzo Fortelli (Rod Steiger, paunchy), who sits Columbo down to a fine lunch to discuss the case. Fortelli and Romano were pals, it turns out, and the old villain isn’t in the least happy to hear of his demise.

Fortelli lays his cards out straight: Romano didn’t kill anyone and the gun found in his hand wasn’t his because it has different ballistics to the gun he always carried. Police have a ballistics report on Romano’s real gun from the prior year. The only person that could have placed the murder weapon in Romano’s cold, dead hand was McVeigh, ergo McVeigh is a double murderer!

Columbo can’t deny that Fortelli makes a strong case, but he still has to follow due process. Fortelli agrees to give the Lieutenant time to bring McVeigh to justice, but if he doesn’t see swift results he’ll take matters into his own hands. I.e. McVeigh will find himself sleeping with da fishes. The convivial dining experience is sadly ruined at this stage, when Columbo discovers he’s been eating CLAM SOUP and has to gallop off to the bogs (click below for suitable sound effect for this calamitous occurrence).

Tracking McVeigh to the race course, Columbo crashes his fancy luncheon to share more news from the case. Phone records do show a call from Romano’s office phone to McVeigh HQ. However, the commotion over the mice means they can’t prove Romano himself made the call. Further to that, the mouse Columbo retrieved from the trash is of a species not native to Los Angeles. Instead, they dwell in the mountains where the McVeigh horse range is located. Coincidence?

Starting to feel the pressure, McVeigh decides to stash Romano’s actual gun away from potentially prying eyes. Instead of lobbing it into the ocean or a lake, he buries it in a shallow gravel grave under a birdbath in his back garden. It’s one of the worst examples of hiding evidence since Abigail Mitchell hid Edmund’s keys in a sand-filled ashtray in Try and Catch Me 17 years earlier.

He was right to start feeling a little tense mind you, because he is paid a visit by Fortelli in person the next day. Accompanied by two goons, Fortelli gives McVeigh an ultimatum: hand over a controlling interest in the ranch by 6pm the following evening or he’ll be a dead man. McVeigh runs crying (not literally) to Columbo seeking help, but the detective shows but scant concern merely offering to look into getting him a police guard. When McVeigh is subsequently accosted by Fortelli’s heavies, who attempt to run him off the road, only a call to the cops from his cell phone saves his skin.

Columbo later reports that the police have put Fortelli ‘on notice’, which ought to prevent any further threats to McVeigh’s life. If this brings some crumbs of comfort to McVeigh, they are quickly dispelled. Asking to borrow a lighter, the Lieutenant comments on how similar it was to a mystery, bearded man’s who was seen drinking at Romano’s restaurant on the night of Teddy’s death. This unknown male also drank scotch and soda ‘easy on the soda’ – the exact way McVeigh favours the drink. This same man is now believed to have been the one who made the call from Romano’s office to Teddy. Rattled, McVeigh orders Columbo off his property.

While trying to bury his woes by focussing on his day job, McVeigh is informed that Columbo has left a message for him requesting his company for dinner at a posh restaurant at 9pm that night. McVeigh, like a good citizen, shows up – but is disturbed when Columbo does not, leaving his date hanging for a good hour. At this stage, McVeigh notices that the barman is the same one from Romano’s restaurant. Finally smelling a rat, he makes to leave but is alarmed to see two of Fortelli’s goons out front and the mob man himself in the kitchen! McVeigh makes a desperate call to Columbo, who promises to be there in 20 minutes.

When the Lieutenant arrives to escort McVeigh away, Fortelli’s goons apprehend them. Columbo is slammed against a wall, while McVeigh has to deal with some severe blows to the kidneys. Fortelli emerges to call off his attack dogs, but this respite threatens to be brief. Backhanding McVeigh, Fortelli rails against the slow progress of the police investigation and threatens to deliver justice his way. “This guy belongs to me now,” he tells Columbo with some heat.

The only loose end Fortelli now has to deal with is the Lieutenant, hinting broadly that if Columbo doesn’t walk away there’ll be two dead bodies to tidy up. After an eternal pause, Columbo turns tail. “I’m sorry, sir,” he says to McVeigh. “They don’t pay me enough for this kind of stuff.”

Driven to desperation, McVeigh screams out that he’ll confess to the double homicide if only Columbo won’t leave him to die. No deal, replies the detective. As soon as I get you out of here, you’ll recant. I need hard proof that you killed the two men and I just don’t have it.

It’s the straw that breaks the camel’s back. McVeigh admits to having hidden Romano’s gun under the birdbath in his garden. A quick call to Sergeant Brindle at the McVeigh Ranch turns the gun up in a hot minute. Fortelli will allow Columbo to take McVeigh into custody but warns the murderer against trying to beat the rap. “I think what he’s saying, Mr McVeigh, is that if you get some fancy lawyer to save you on a technicality, he won’t be saving you.”

McVeigh submits and is permitted to leave by Fortelli, who shares a colossal thumbs up with Columbo. As McVeigh is driven away in a police black and white, the conversation between law enforcer and criminal kingpin confirms that they had planned this entire charade together. Even Fortelli’s henchman were undercover cops. Despite this comradeship, Columbo refuses the offer of a farewell drink with Fortelli. “It’s just that I’m a cream soda type guy… and you’re not,” he says. With that, the Lieutenant takes his leave as credits roll…

My memories of Strange Bedfellows

One of the Columbo episodes I have seen least (possibly only once or twice ever), Strange Bedfellows takes up extremely limited space in my memory palace. Going into the viewing, my only real recollections are of believing George Wendt to be horribly miscast; finding his beard disguise laughable; enjoying Rod Steiger’s role; and, most importantly, being aghast that Columbo would ever enter into a deal with the mob to achieve case closure.

Details of either murder escaped me (I didn’t recall Bruno Romano at all), I couldn’t remember anything about the support characters beyond George and Rod, and overall cannot escape the vague impression that this is a woeful late Columbo offering with little to recommend it. Could I be surprised by a blockbuster adventure upon a fresh viewing after a very long hiatus? Don’t bet on it…

Episode analysis

Ever since we’ve known him, we’ve known that Lieutenant Columbo is not averse to playing games with his suspects in order to catch them out. Indeed, some of his most memorable cases involved him acting in ways that pure-hearted viewers may have found hard to stomach.

He blatantly plants evidence to expose killers in Death Lends a Hand and Dagger of the Mind. He creates false evidence to draw a crucial mistake from Paul Galesko in Negative Reaction. In A Matter of Honor, he stages a set piece with a killer bull that could genuinely endanger the life of his chief suspect. During Ransom for a Dead Man, he conspires with young Margaret to terrorise Leslie Williams in her own home and get her to part with the hidden ransom cash that will prove her involvement in murder.

The events of A Case of Immunity see the Lieutenant collude with a King and leave the threat of death hanging over Hassan Salah in order to get the First Secretary to waive his diplomatic immunity. And in Mind Over Mayhem, he stages the phony framing and arrest of an innocent son in order to elicit a confession from the father. There are some seriously murky acts in that list, but for many viewers Columbo’s actions in Strange Bedfellows represent the unpalatable nadir of his career.

The Lieutenant has made some unlikely allies in his time, but surely none compare to a hardened criminal like Vincenzo Fortelli: a man whose shady past has mixed him up in prostitution, gambling and, y’know, murder. Columbo willingly enters into a pact with Fortelli that will ultimately ensure Graham McVeigh pays for his actions in the eyes of the law, but do the ends justify the mean? Or to put it another way, does the moral gain of bringing McVeigh to justice outweigh the moral loss to Columbo’s character of putting his key suspect through the physical and emotional wringer – however abhorrent his crimes?

How the viewer feels about this critical question will likely have a significant impact on their enjoyment of the episode. If you believe Columbo was just employing his ‘shop-worn bag of tricks’ to turn a difficult case to his advantage, Strange Bedfellows may be right up your alley. If you hold the Lieutenant to higher moral standards, the episode may be one that you can never entirely take to heart.

It perhaps won’t surprise readers to hear that I fall into the latter camp. For all the things Strange Bedfellows does well (and there are a few decent highlights to be found), almost all the goodwill it garners evaporates by the time credits roll due to the deeply unethical charade Columbo embroils himself in. Make no mistake about it: Columbo’s complicity in the mental and physical torture of Graham McVeigh is several steps further into the abyss of immorality than we’ve ever seen him take before.

The detective allows the life of his key suspect to be recklessly endangered several times. Two officers masquerading as Fortelli’s thugs bash bumpers with McVeigh during a high-speed chase – an act which is impossible for anyone to predict the outcome of. The terrified McVeigh could easily have lost control of his vehicle (especially while using his cell phone), flipped his vehicle and been barbecued in a car explosion.

Later, in the restaurant showdown, McVeigh is properly roughed up by the same undercover cops and then savagely backhanded by Fortelli and menaced in such a way that he must have believed his life was about to be ended. Again, Columbo could have no idea how such a scenario might pan out. A hefty fellow, McVeigh’s heart could have packed in under such duress, killing him outright. Or he might have had a gun stashed on his person and started firing indiscriminately in a last-gasp bid to save his own hide. Would any of those outcomes be acceptable to the Lieutenant we know and love? Not a chance.

And before anyone rolls their eyes and whispers “geez man, it’s just a TV show, get over it,” I’ll put on the record again that I hold Columbo to higher standards than other run-of-the-mill police dramas. The inherent goodness at the heart of the Columbo character should be sacrosanct. In Strange Bedfellows, Columbo doesn’t just fall below his expected standards of conduct – he doesn’t appear to feel a shred of remorse about his actions.

Think back to Negative Reaction. After tricking Paul Galesko into incriminating himself, Columbo couldn’t look the man in the eye. Similarly, he apologised for the arrest of Neil Cahill to father Marshall in Mind Over Mayhem. And when the King of Suari flashed him a thumbs up at the end of A Case of Immunity, Columbo looked downright ashamed of himself. We could see in each of these examples that the man himself was not immune to the consequences of his actions. He had achieved his vision of victory, but took little pleasure in doing so.

In Strange Bedfellows, the treatment of McVeigh was far more extreme and far less forgivable than any of the above cases. Yet Columbo trades friendly thumbs up gestures with Fortelli once McVeigh is firmly in his clutches, and the pair then have a perfectly civil chinwag before a friendly parting of the ways. Sure, Columbo turns down Fortelli’s offer of a drink, but he hardly seems to be beating himself up about his actions. That hurts the character, and it hurts me to see it.

Columbo supporters could claim that he genuinely believed the only way to prevent McVeigh’s execution was to partner with Fortelli to scare the man sufficiently to make him divulge the location of the elusive evidence (Romano’s gun) that would prove his guilt. And because this scheming took place off-screen we’re not party to how the discussions played out. Perhaps Columbo strenuously disagreed with the plan, but was overruled by a superior officer. However, his lack of overt unhappiness at the conclusion of the case would tend to dispel this notion.

I would think it would be truer to the Lieutenant’s nature to have an honest discussion with McVeigh about how his only chance of survival would be to make a clean breast of it, admit his guilt and take his punishment. Given Columbo’s everyman appeal, this approach seems as likely as any to result in a conviction without having to traumatise McVeigh in the process. Still, that perhaps mightn’t make for the most gripping TV and it can at least be argued that Strange Bedfellows delivers an action-packed finale by the series’ standards.

If Columbo’s dalliance with the dark side is the episode’s most questionable element, it’s not the sole reason why Strange Bedfellows falls well short of vintage status. For one thing, it’s awfully repetitive, dredging up all sorts of boring TV tropes and repurposed plot points from earlier Columbo outings. Feuding brothers struggling to see eye to eye over the benefits of a shared inheritance, leading to one bumping off the other is highly reminiscent of Any Old Port in a Storm. Even McVeigh making his getaway on a silly little fold-up bicycle is a straight lift from the 1973 classic.

The finale is like the gotcha from A Case of Immunity on steroids, while the tedious and unimaginative gambling backdrop plunges the episode into a miasmic melding of elements from Columbo episodes old and new. Young, useless Teddy McVeigh is as addicted to trouble and betting as Harold McCain in A Bird in the Hand, while his love of the gee-gees conjures up unwelcome comparisons to Uneasy Lies the Crown killer Wesley Corman. Personally, I find nothing more boring than excess gambling used as a plot device in murder mysteries, so Bedfellows had me offside right from the start.

McVeigh’s general uselessness as a killer is another point of contention. He easily fulfils the membership requirements to joins the Bungling Columbo Killers Club so feeble are his efforts to remain inconspicuous and unconnected to the crimes. Like Marshall Cahill, Joe Devlin and Eric Mason years before, McVeigh is so inept that it would be harder not to suspect his direct involvement in cold-blooded murder.

Based on my Columbo-watching experience, a golden rule of murdering someone is to ensure that at no stage during the build-up, the crime and the clean-up should you do any of the things you would normally do. So if you’re at a bar in a daft disguise, don’t order your usual drink in the exact same way you always order it. Instead, choose an outlandish concoction like pink gin and lemonade or Malibu and milk – something that you’d never normally drink in a million years.

If you must feed your tobacco addiction, smoke a pipe of scented, apple tobacco and light it with matches, not an ornate and highly memorable golden lighter. Similarly, if you’re in the victim’s car with them immediately prior to ending their existence, go a few minutes without smoking, or at least leave a huge Cuban smouldering in the ashtray to fool the po-po.

McVeigh not only makes these stupid, avoidable mistakes – he carelessly exacerbates them by openly smoking in front of Columbo seconds after meeting him, and later ordering his trademark whisky and soda ‘easy on the soda’ within earshot of the detective, just as he did at the bar of Bruno’s Ristorante on the night of Teddy’s death. He may as well have just printed and worn an XXXXXXL-sized t-shirt with I’M GUILTY emblazoned all over it.

As well as these basic howlers, McVeigh also acts in an illogical manner. I mean, why even bother taking the risk of killing Romano at all when the death of his brother ought to be enough to grant him the easy life he seems to crave? And why on earth would he hide Romano’s gun in his garden when he could have flung it in a river or hidden it in mountains near his home? Such a move only serves to give him wriggle room to avoid execution later but no actual killer would be so cavalier with such damning evidence.

The credibility of the McVeigh character isn’t helped by casting George Wendt in the role. I’ve nothing against the guy, but his limitations as a dramatic actor are clear as day here. Immortalised as Norm from Cheers to tens of millions of viewers over 270 episodes of the sitcom between 1982-93, Wendt is much more at home in comedic roles and he has nothing like the gravitas required to make for a believable Columbo killer.

The episode writing also makes Wendt’s casting extra puzzling. Graham McVeigh lamely disguises himself twice during the episode – firstly to buy the gun from the pawn broker, and again later when he glues some fluff to his face and frees some mice in the ladies’ bathroom at Bruno’s restaurant. However, the most remarkable and memorable aspect of Wendt is his massive bulk. Tall, wide and round, he’s a whole lot of actor. It therefore stretches credibility that witnesses who remember his lighter and favourite drink don’t appear to have passed comment on his sheer size.

Columbo’s key suspect is a bearded, hatted man who uses an ornate gold cigarette lighter (just like McVeigh’s) and who drinks whisky and soda ‘easy on the soda’ (just like McVeigh does). Throw in a description of the man also being as wide as a wardrobe and Columbo could collar him straight away. And before I’m accused of being fattist, nothing could be further from the truth. I just feel that the killer in this episode ought to have been an unassuming, unmemorable type who could fade into the background wherever he goes. Wendt can never do that, making his casting another example of new Columbo shooting itself in the foot.

Wendt’s not alone in struggling to deliver the goods in the lofty company of Peter Falk and Rod Steiger. In a tiny role as Teddy’s love interest, Tiffany evidently studied at the Dick Van Dyke School of English Accents, dishing up such aural treats as “‘Ere, don’t be a bleedin’ pain, alright?” lest viewers fail to realise she’s supposed to be British. Cast as Teddy, Jeff Yagher is every bit as underwhelming as his career credits suggest, while Jay Acovone’s Bruno Romano makes so little impression on the episode that I’d wager he’s the series’ single least remembered victim.

Thank goodness, then, for the presence of Rod Steiger as Vincenzo Fortelli. The character’s a Mafia cliche, of course, but Steiger’s performance is electrifying, veering from snarling menace to fatherly affability with ease and grace. Some critics say he was dialling in his performance here, but I just can’t agree. He’s terrific, and comfortably head and shoulders above the rest of the supporting cast.

Regardless of whether it’s all a set-up, Fortelli’s raging at both McVeigh and Columbo during the restaurant showdown is masterful. Steiger makes it easy for the viewer to believe that both men are viable candidates for assassination such is the power of his performance, but it’s the way he shifts his tone from gravelly roar to almost a whisper when claiming to be “the judge, jury and executioner” in the McVeigh case that is most chilling. He’s a truly dangerous presence and certainly one of the most interesting supporting stars of Columbo’s revival era. A whole episode of Columbo vs Fortelli would have been a mouth-watering prospect.

As was the case with It’s All in the Game, playing opposite a titan of the silver screen (here Steiger, there Faye Dunaway) seems to have done wonders for Peter Falk. The scenes the two share are powerful, no-nonsense and playful in a way that hooks the audience, but Falk is on terrific form throughout. Regular readers will know how little I like seeing Columbo lapsing into silly tomfoolery (tuba playing etc), and there’s mercifully little of that to be found in Falk’s performance.

His interactions with McVeigh hark back to the show’s glory days, with the detective playing it all dumb and innocent, allowing his suspect every opportunity to be too helpful and then zapping him with a telling observation or impeccably timed “one more thing”. I must also pay credit to how convincingly Falk played the upset stomach card during his opening scenes. His expressions and mannerisms as he swigs the hated pepto bismol have an authenticity all too often absent in the Columbo portrayal post-1989.

The only real beef I have with Columbo in this episode (aside from partnering with the mob, natch) is the inconsistency surrounding understanding of Italian. When Fortelli’s goons grab the Lieutenant and deliver him to an unasked-for lunch meeting, he pretends not to understand anything the mob boss is telling him in their native tongue, although he wryly hints later on that he’s fully au fait with all that was said.

Of course, we know from episodes such as Murder Under Glass and Identity Crisis that Columbo is well able to converse in Italian. However, his fluency largely depends on the circumstances he’s in and whether or not it’s to his advantage to reveal the depth of his understanding. When Columbo tells Fortelli he doesn’t speak Italian, he’s being dishonest. It’s his way of putting a barrier between himself and the gangster. But when he fails to pick up that the Zuppa di Vongole served to him is clam soup, the scene is thrown into disrepute. Either it’s a continuity error or, more likely, a means of throwing in a cheap gag about Columbo’s dodgy, clam-intolerant guts. Booooooo, hisssssssss!

There’s further inconsistency in the rodents-in-the-restaurant subplot that caused me some confusion during this viewing. We see McVeigh place a small box into the ladies’ bathroom and later witness a patron screaming blue murder about rats having crawl all over her when she was powdering her nose. When Columbo visits the restaurant he’s informed that two tiny mice were caught in traps later that night, yet the one he fishes out of the dumpster is a hideous GIANT of a beast and certainly large enough to pass as a rat.

Are we to believe that two of these creatures were in the box McVeigh slipped through the loo door? Hardly plausible. And why would the barkeep claim they were tiny when the specimen Columbo uncovers is almost the size of a guinea pig? It’s not of major importance to the storyline but is indicative of some muddling writing that could have easily been avoided.

Interestingly, episode writer Peter S. Fischer, who had been involved in the show on-and-off since the mid-1970s, wrote the initial script for Strange Bedfellows but was so unhappy with the end product (and the casting of George Wendt in particular) that he disowned his involvement and is credited under the pseudonym Lawrence Vail.

Quite how many alterations were made to his script are unclear, but Fischer previously adopted the Vail nom de plume when his script for 1976’s Old Fashioned Murder was torn to shreds by Peter S. Fiebleman and Elaine May in one of the most shambolic productions of the 70s. It’s a fair guess that his original draft to Strange Bedfellows was somewhat different to the version we see on screen but, alas, I have nothing concrete to back up that assertion.

Elsewhere, hardened fans will welcome the return of Bruce Kirby (in his ninth and final series’ appearance) and John Finnegan (in his 10th of 12 appearances). Kirby is playing a dependable police sidekick to Columbo once again, only this time he’s rather pointlessly cast as Sergeant Phil Brindle instead of the usual Sergeant George Kramer. Finnegan, meanwhile, is back as diner-owner Barney after also assuming the role in It’s All in the Game. As always, the mere presence of these popular character actors is a welcome call back to the show’s classic era.

If only the same could be said for the calibre of Strange Bedfellows as a whole. While it has some entertaining moments, its ludicrous elements make it impossible to take seriously despite the efforts of Falk and Steiger. Were this a standalone movie mystery it could conceivably be passable fare, but its lack of substance and gaping plot holes earmark it as a weak entry into the Columbo universe.

With the killer leaving so obvious a trail of breadcrumbs to his own door, the shock value of the twist in which it is revealed that the Lieutenant has sided with the mob to bring McVeigh down also has a hollow ring to it. McVeigh is an inept boob without the mettle to stand up to the rigours of a serious police investigation. The Columbo of old would simply have worked harder to get the evidence he needed when the killer’s guilt was so clearly established without ever considering – let alone actually entering into – an alliance with gangsters.

The bait-and-switch finale might seem clever on first viewing but becomes increasingly unpalatable under closer scrutiny as yet another quality of a character we treasure is carelessly tossed away. And that’s really Strange Bedfellows’ striking legacy: in seeking to provide a thrilling parting shot it manages to undermine more than 25 years of careful character curation.

How I rate ’em

Another flaccid effort, Strange Bedfellows has its moments but its many flaws see it plunge into the bottom tier of new Columbo outings. It’s not as bad as the dreaded McBain episodes, but that’s hardly a glowing endorsement. One to avoid.

To read my reviews of any of the other revival Columbo episodes up to this point, simply click the links in the list below. You can see how I rank all the ‘classic era’ episodes here.

- Columbo Goes to College — top tier new Columbo episodes —

- Agenda for Murder

- Death Hits the Jackpot

- Columbo Cries Wolf

- It’s All in the Game

- Rest in Peace, Mrs Columbo

- Columbo Goes to the Guillotine — 2nd tier starts here —

- Sex & The Married Detective

- Caution: Murder Can Be Hazardous to Your Health

- Butterfly in Shades of Grey

- A Bird in the Hand…

- Murder, A Self Portrait

- Columbo and the Murder of a Rock Star — 3rd tier starts here —

- Murder, Smoke & Shadows

- Uneasy Lies the Crown

- Strange Bedfellows — 4th tier starts here —

- No Time to Die

- Grand Deceptions

- Undercover

- Murder in Malibu

That’s all for today, friends. Do have your say on Strange Bedfellows in the comments section below. Can you accept Columbo’s actions in this episode, or do they irreparably damage the character? How do you rate George Wendt as a killer? And are there any glowing highlights I’ve overlooked that you believe warrant a mention?

I’m now going to lie down in a darkened room and try not to think about Strange Bedfellows again for the next few years. The next stop on the Columbo train is A Trace of Murder – an episode that wouldn’t air for more than two years after this one. A sign that the show is ready to call it quits, or a welcome hiatus to allow the production team to come back better than ever? Let’s wait and see…

This episode was steaming hot trash. I agree with every point in this review. Wendt was terrible, the deal with the mobster was completely antithetical to everything Columbo. This is worse than the Ed McBain episodes in my opinion.

Jason, I take you didn’t even like Steiger’s sumptuous clam dish he served to Columbo? My fave part of the episode and it always made me hungry!

It gave me a tummy ache even worse than our Lieutenant’s!

Imagine the toilet blowout Columbo had after gorging himself at Creighton’s expense in Rock Star. And who could blame him? Chili and hardboiled eggs tend to get boring after a while! 😀

Watching Strange Bedfellows this morning and losing it right at the start. On a sunny day in Southern California, George Wendt is trying to look inconspicuous by wearing a black trench coat and black hat?? Could he possibly look more conspicuous?

Wendt is way out of his depth in this episode. I support anything Columbo does subsequently simply because the “disguises” are so ridiculous.

I’ve never felt Columbo feels guilty about tricking Galesko (that was a superb move) – remember how he looked down after proving that the candidate for senator killed his manager? That was the same manner – it’s rather a dissapointment in humanity, but not the guilt in oneself.

It always perturbs me when filler dialogue is stupid. It would be all but impossible for a batter to have 103 RBI and hit .110 with men on base. For the benefit of British host, an RBI is earned by driving in a man on base. Or yourself, but if we subtract his 37 home runs, he still still has 66 RBI. Although in theory he could and probably sometimes has driven in more than one man at a time, it still would mean about 600 or more at bats with men on bas (and that would be assuming every time was either an RBI or an out, with not a single, or at least no more than a tiny handful, at bats of advancing the runner without driving him in). I would bet no batter in MLB history ever had a statistical line close to this.

Art does not always have to be a moral compass. Columbo becoming allied with a mafia boss is not sympathetic of course, and I don’t like that either. But judged as a piece of television (acting, direction, aesthetics, use of music and so on), I think this episode is quite good, and it is nowhere near the bottom. I’d much rather watch this than, say, Undercover or the Commodore.

The depiction of mobsters is very stereotype, but I guess it was done with a twinkle in the eye: it is poking fun at the cliches of mobsters rather than mobsters as such.

My biggest issue with the episode is probably the gotcha; it seems rather pantomime to me.

Two comments only tangentially related to this episode (which I actually quite liked but don’t want to get into that):

First, every time I hear that gunshot effect when Columbo drives his car I hope it’s somebody shooting the damn foley artist. Maybe they can issue a remastered series of episodes with this highly annoying overplayed joke removed.

Second, while they’re at it they could massively tone down the “This Old Man” theme. On that point, do you think we would find it quite as annoying if the Barney theme song hadn’t come along?

Now look, I like this episode. Sorry but I do. Something to do with the clams. But I do have two problems. One, why did they cast Bruce Kirby and yet not change the character name to Sergeant Krammer. That’s just ridiculous.

And Two. Why is Barney’s restaurant completely different? Why is it suddenly called the Crossroads Cafe? Columbo is supposed to have been eating there for nine years yet it’s nothing like Barney has ever worked in! C’mon! I mean we know the continuity on Columbo’s favourite eateries is bad, but seriously…

And one more thing. Scotch and SODA??? I mean, the man deserves everything he gets…

Yep, just like the cioppino in Murder: A Self Portrait, the clams made the episode! Btw, I like my scotch neat and on the rocks…

This episode started out good. But I thought that the ending was controversial. The police and Columbo are working with the mob to get a forced confession from suspect McVeigh (Norm from Cheers) (George Wendt). Had this gone to the press, it would have created a huge scandal, aside from an aquittal. I actually thought Wendt was good in the part. He had a good straight “poker” face. The horse gambling and mob connection was good. McVeigh though was very sloppy, not wiping the ashes from the car, his scotch and soda orders, and that goofy mountain man costume. I thought the scenes done at the horse track were effective. It was cool to watch the horses race. This could have been a better episode. Rod Steiger’s mere acting presense saved this episode. Very convincing as the mob boss Fortelli. Columbo’s partnership with the mob to solve the crimes was unsettling. A better story could have been told.

Just rewatched this on the back of Columbo Goes Guillotine. A lot of contrast but both are of course on the bleak end of the grayscale. Both episodes would make better graphic novels by a talented sketch artist then prime time TV. (BTW this would make a great project for an aspiring graphic novel team). Anyway this episode, despite all its crappiness and potholes, is strangely friggin watchable! Go figure. I think it is that the actors aren’t trying real hard, and Wendt, Falk, and Steiger are so easily just being “a character” onscreen, versus delving into a character. Given the writing, delving would have been akin to jumping into a septic tank. So what carries it beyond personalities? Ye olde mob story. We, Yanks in particular, sure do love us a mob tale, the numbers back me up. TV was relatively slow on the uptake (vs. lit and movies) to create comfortable mobsters. The gotcha of the mob working in concert with LA’s fines is laughable but overlookable. “We’re all just having fun here”. What kills me about this episode, as well as Guillotine, is the friggin dumb as hell “This Old Man Came Rolling Home” played on a crapsichord as the closing credits roll. Ruins it. 80s and 90s TV production is so horribly defaced by arsonists in the form of production assistants allowed to purposely build in shitey stuff to accommodate production and directorial laziness/lack of talent. I sure do hope this indigestible suffix is due to tertiary clowns and not prime movers.

Note that that the murderer’s last name is McVeigh, the same last name as Timothy McVeigh, the person responsible for the Oklahoma City bombing. Strange Bedfellows aired a month after the Oklahoma City bombing.

It’s possible that this was a coincidence, as it was written and produced long before the bombing took place.

However, it’s also possible that writer Peter S. Fischer included the name as a nod to current events, since the episode aired only a month after the bombing.

Either way, it’s an interesting coincidence and a reminder of the power of names and the associations they can carry.

Why did Mc Veigh kill Bruno ?

Is there a law, or mafia law, that he inherits his brother’s debts ?

And lest we forget, the by now WAYYYYYYY too cutesy “This Old Man” theme inserted into almost every episode. Nooooooo….!!!

About the morality of Columbo’s pact with Fortelli, I think you forget one thing. Early in the episode, Fortelli says he’s done with his old life, and that he’s gone fully legal, with all taxes paid (that must have involved jail time, I should think).

I hadn’t forgotten that, I just don’t think for a second he’s telling the truth!

I dunno, you knock over a few banks, arrange the assassination of a couple of rivals, run the local protection racket for years and then no one believes you when you say you’ve put it all behind you! Hey, what’s a guy gotta do?

One question I keep returning to while I think about high “bodycount” of scripts butchered by Falk and co. during the ABC run is how on earth did he manage to direct “Blueprint for murder” way back in season 1 and not make a wreck of it? Just rewatched it today. A perfectly competent job, even impressive one for a first-time director (and one of my childhood favorites long before I ever paid any attention to the fact that it was directed by Falk himself).

What was it that helped him back then? Better studio supervision? Less pliable screenwriter? Or was it just the fact that he found himself in a “do-or-die” situation when his request for a directorial job was eventually granted?

In Season 1, Levinson and Link were in charge. Falk pushed, feigned illnesses, etc. — but the show’s content was under L&L’s control. Their day-to-day responsibilities ended after the first season. They left several Season 2 stories behind, and then served as consultants for the remainder of the NBC run. For the ABC run, there was no Levinson (he died in 1987), and Link was given a fancy title but his role was very limited. The entire power structure was different.

In their book Stay Tuned, Levinson & Link wrote that they gave Peter Falk Blueprint For Murder to direct because that script had many built-in pitfalls that would have frustrated even an experienced director.

In particular, the use of an active construction site as a location stood in the way of Falk’s constant desire for retakes; they couldn’t just stop and go back with the building process.

That Falk didn’t take another directing assignment didn’t surprise Levinson or Link …

Just so you know…

It’s also called “The porcelain god” because you kneel before it.

Coming back to an idea I have had…

Is it possible that Fortelli was going straight? That he had left his life of crime behind and was striving to gain respectability?

Before writing this off, consider that Fortelli’s getting on up there (Rod Steiger was nearly 70 at the time), and might be yearning to go into a respectable retirement. There are more than a few examples of mobsters doing their civic duty as they get older, or at least not killing people anymore. “The Godfather, Part 3” was about Michael Corleone trying to be Mr. Good Citizen.

Fortelli could have decided to cooperate with Colimbo with a wink-wink-nudge-nudge acknowledgment that he, Fortelli, is an honest man pretending to be his old self in order to nab a murderer.

I’d like to see a Columbo reboot of Columbo’s nephew as detective. Smartly dressed and trying to make his own way. His brother’s son, Vito Columbo.

I can’t understand why McVeigh didn’t simply leave it to Romano to rub out his wastrel of a kid brother, was it simply to give us the immense pleasure of watching him ride away from the murder scene on that little bike?

In a comment I sent you awhile back, I mentioned that this particular episode brought to mind a real-life murder case that became well-followed here in Chicago, in between the two runs of Columbo.

There’s a section of Chicago known as the Gold Coast, home to a well-moneyed set that raises horses and lives pretty high on the hog, with little regard for legal niceties and a casual attitude to what we refer to (not entirely without affection) as “The Outfit.”

There were Silas Jayne and his younger brother George, who more or less correlated with the McVeigh brothers here; Silas was “mobbed up”, while George was independently profligate, which led to ill will between the two.

Long story short: George was murdered, Silas came under suspicion, and (it says here) the Chicago PD reached an “accomodation” with The Outfit to bring Silas to justice … or something like that.

I have no idea how Peter Fischer came to learn about the Jaynes (he admits nothing in his own book), but it’s really too much of a coincidence …

Anyway, when Fischer’s name was still on the script (and this is in his book), his suggestions were along the lines of James Spader or James Woods; how George Wendt came under consideration – maybe someone recalled that George was a native Chicagoan, with perhaps a little passing knowledge of the true story that he might add to the mix (don’t rule out the possibility that Wendt {whose IRL brother-in-law was a State’s Attorney in DuPage County, right next to Chicago} might have campaigned for the part himself).

Most, if not all, of the foregoing is speculation; the whole story may be lost to history …

Maybe Peter Fischer took the false name for a reason other than that he didn’t like the script…

I guess, theoretically, Fischer might use his Vail pseudonym — his “official don’t-blame-me-for-this-piece-of-crap cop out” — only because the casting, direction, and production had turned his script into a “piece of crap.” For example, Fischer objected strongly to the casting of George Wendt. However, Fischer’s express objections here also focused squarely on the script changes Falk and McEveety made: “Peter and Vince fiddled and diddled with the structure and the clues to the point where it became incomprehensible nonsense.” [Ironically, the only scene he liked was the final Fortelli-McVeigh-Columbo confrontation.]

Haha, I meant in my above comment, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, that Fischer didn’t want his real name attached to an actual case involving the mob.

I’ve often wondered why Silas Jayne hasn’t inspired more writers, when the Horse Murder scandal and the people involved in it have inspired novels, movies, and countless tv shows. I think it comes down to how repulsive his crimes were, and the fact that he was never punished for them: He died an eighty year old millionaire. Could the car bombing in “A Bird in the Hand” have been inspired by the accidental killing of Cheryl Rude, George Jayne’s secretary?

George Wendy may have been miscast as the murderer, but the character was so shambolic that I don’t think any actor could have made it work.

Agree with most on here, but, all in all, I found Strange Bedfellows to be on par (meaning mediocre) with many of the rest of the new Colombos.

My observations:

# Falk was outstanding here

#The need to just kill the brother seemed harsh.

#When the police showed up after Bruno was murdered, was there any mention of why he had $200,000 so readily available?

#The mouse Columbo found was WAY too big. Did you see the tiny size of the box GW placed in the bathroom? And there were two of them in there?

#I’m curious of what others think here…at what exact point in the episode did Columbo and the mom boss start their scheme?

#Were the original two mob henchman the same characters as the two undercover cops at the end? I don’t think so, but they looked similar.

#As somebody who has never committed a crime, I would rather be killed by the mob then spend the next 50 years of my life in prison.

# What faith can we have in the police- particularly Columbo! – if they choose to work with the mob on a case? It left me wanting a shower at the end. And it left me not trusting a police lieutenant. Not good. I cannot stand organized crime, and here, our beloved Columbo works with them.

#Having said all this, I thought it was a decent episode if you replace GW with another actor and did away with Columbo working with the mob.

A fairly entertaining episode diluted by completely illegal Police behavior. As several here have wrote, why would they do this to a Columbo?

Agreed on all counts, though I must admit the denouement didn’t bother so much from an ethical standpoint as it did in its presentation. Wendt flailing about was one of those incredibly silly moments that were all too common in these final few episodes.

One must wonder how Wendt’s former bar mate Frasier Crane would have fared as a villain against Columbo. Would have loved to see Kelsey Grammer in all his snarling blue blood glory as a murderer.

Kelsey Grammar as a murderer sounds good to me too.

While he never got the chance on COLUMBO, Grammar played a murderer in a Columbo-like episode of J.J. STARBUCK in 1987. We see him commit the murder in Act 1 and he was an affluent concert pianist. (Many STARBUCK episodes were derivative of Columbo). Not a bad episode, probably the closest we’ll get to Grammar as a Columbo villain.

Shani Willis, she of the awful Cockney accent, actually was English (b. in north London, ground Zero for Cockneys). She played Nancy in the movie version of “Oliver!,” and she was great.

Gor blimey, strike a light!

Strange Bedfellows? More like Strange Bedbugs. Arguably, one of the sleaziest of the new Columbos with our good detective abandoning all principles to catch the perp. Whatever happened to “you can’t win em all” as Columbo says to Bart Kepple in Double Exposure-one of my favorite episodes from the 70s. After watching Strange Bedfellows, I felt like I needed a shower and a tube of hydrocortisone cream to relieve the itch. On a positive note, Rod Steiger was great as usual and Peter Falk played his role seriously for a change, avoiding his Columbo Goes to Clown School antics- all too common in the new episodes.

The problem with the confession is not just the mob boss. It is that even with all the evidence Columbo gives up on solving the case and basically beats the confession out of the murderer. In fact, he uses policemen to literally beat the murderer up. Not sure why the mob boss was needed at all. The cops could just have taken anyone, beat him up and make him confess. Like we know cops often enough do.

This is the difference to the other examples – like the diplomat which *is* proven guilty by the evidence and uses his immunity to escape the normal procedure, which then is prevented by the king. The case itself is still rather solid.

In Death Lends a Hand he sets a trap – the reaction to this itself is the evidence.

In Dagger of the Mind the mudering duo is at its brink anyway (in their cartoonish Mac Beth variation) and the ruse itself is irrelevant.

In Negative Reaction he appeals to the murderers hybris.

None of this would have ended badly for an innocent accused or perhaps just somebody with stronger nerves.

In this case anybody would have confessed. This was a “The Judge and His Hangman” ending of moral failure, which only could have worked as an interesting take, had this been presented by the show as such.

This makes it de facto an unsolved crime.

The mob boss was needed to ensure that McVeigh couldn’t challenge in court the coercive conduct that extracted from him the evidence of his guilt. If he did, he’d be killed. Columbo personally reinforced that message: “If you get some fancy lawyer to save you on a technicality, he won’t be saving you.” (Columbo took center stage to drive that point home. Before this, he could pretend it was all Fortelli. No longer.)

I’d say the “trap-springing” episodes aren’t the strongest, as a matter of principle. “Death Lends a Hand” is the obvious exception, and “Negative Reaction” was pretty good, too, although the trap in that episode wasn’t as strong. “Dagger of the Mind” and “A Matter of Honor” are examples of the flaws of the concept, given Columbo’s normally easy-going nature and evidence-based detective work. SB takes the trap-springing/set piece concept to the extreme and exposes its flaws, creating a substantial discontinuity in the Columbo character.

But aren’t they among the most memorable gotchas? “A Friend in Deed”? “A Deadly State of Mind”? Both trap-springers. “Troubled Waters”? Columbo cons Danziger into planting a second pair of gloves with powder burns, oblivious to what he’s leaving inside. All top-drawer episodes.

Better than i used to give it credit for good moments but theres truck loads of faults with it prefferable to undercover anyday not as good as a trace of murder which is next wathed agenda for murder yesterday which is the best new one for me with death hits the jackpot 2nd and goes to college in third

Yeah, I agree that those three are the strongest trio of the new series.

Unlike most here, I enjoyed this episode. I’m aware it’s a departure from the serious standard of Columbo, and I would wholeheartedly reject most cases of such an absurd departure from any series’ norms. However, with this episode’s clever scripting and character development, I’d say the episode is sufficiently entertaining to overcome its inevitable flaws, and if it weren’t an episode of Columbo, I suspect many of the show’s viewers would regard it highly. Indeed, it’s the departure from a realistic and otherwise unshakable character that makes this episode almost sinful for a purist.

I think Rod Steiger plays the send-up of the gangster movie persona remarkably well. (The guy did play Al Capone in the eponymous movie.) And I find that send-up hilarious, leading me to like this episode more every time I watch it. I’ve hardly watched Cheers and what I’ve seen, I haven’t liked, so there’s no question that my lack of exposure positively impacted my view of “Norm” as a less typecast character.

And sure, SB’s ending is absurd, but that doesn’t make it less enjoyable unless the atmosphere of the episode is directly contrasted to the Columbo “gold standard” of the 70s, which, I dread to say, apart from a few isolated examples, never returned in the 90s.

All in all, I’d rank this episode #6 of the new episodes, below the excellent “It’s All in the Game” and roughly even with “RIP Mrs. Columbo.” I think we’d all agree SB is not among the series’ finest moments, but for me it’s a respectable addition to Falk’s wide-ranging repertoire that’s best forgotten when considering the definition of “Columbo” as a style of TV.

In other words, I watch it, enjoy it, then damnatio memoriae!

And like in undercover I seem to be the only one to like this episode, I find it an average episode, however your arguments about columbo working with the mafia being out of character are sound, in particular a poster mentioned he doesn’t like that in this episode the mafia is above the police, as in that columbo never even tried to solve any of the murders committed by them, I also don’t like that at all.

Finally, in the columbophile review, when talking about columbo’s lack of remorse, there’s a moment which hasn’t been included: in the very end of the episode, columbo asks fortelli if, hadn’t they agreed on their plan to force graham to confess, he would’ve actually killed him and fortelli refuses to answer: I get the feeling columbo didn’t consider fortelli a real threat to graham’s life.

Hated that episode. Why he had to kill his brother in the first place? And that absurdly convoluted scheme involving the Mafia? What was he thinking? The ending was abominable. An episode to bury in an unmarked grave

I appreciate CP sharing the theory, even if he doesn’t espouse it, that Columbo’s chicanery to force a confession was essential to save McVeigh from the vigilante butchery he would have inevitably suffered in short order. Seen through that lens, and since the Lt. already obtained his plethora of circumstantial evidence the old honest Columbo way, painting an albeit overly dramatic picture of McVeigh’s two real options feels far less like an unethical shortcut and more like a necessary evil.

All that said, now that I’m done playing devil’s advocate, this episode still rings false on several notes. CP covered most, such as McVeigh not needing to kill Bruno at all much less via the risky way he went about it. But what bothered me most was the inherent assumption that the mafia is not only above the law, but even rightfully and humorously so — such that a good cop like Columbo would be more apt to conspire with the don than investigate him. Apparently all of this mob family’s past murders are airtight and unworthy of Columbo’s genius attention. The don has the gall to tell an ACE HOMICIDE DETECTIVE outright that he’s going to kill McVeigh out of vengeance. Isn’t this the exact kind of arrogant privileged yutz that we want our beloved Columbo to take down. Yet we are meant to just accept that only McVeigh’s crimes are worth solving. The mafia — which set these events in motion by putting an illegal squeeze on the gambling addict in the first — are thumbs up heroes in Columbo’s eyes! What, because he’s Italian?

That’s infuriatingly inane.

I can’t help thinking that in a more realistic scenario, McVeigh would most likely end up in witness protection in return for testifying against Fortelli. I mean sure, he’s a murderer, but Fortelli is a MOB BOSS. Which do you think the police are likely to prioritise? How many murders has Fortelli himself been responsible for over the years?

Not sure whether this episode is objectively worse than the Ed McBain ones. But found the ending so repulsive that I would choose to watch any other episode including “No Time to Die” or “Undercover” over it.

Unlike some of our dear regular commentators, I wouldn’t rank this episode below the ones at the bottom of the list, based solely on the entertainment factor, which I think is higher here compared to “Murder in Malibu” and the Ed McBain stories. Notwithstanding, the arguments presented seem more than valid as the episode takes a blatant nosedive at the end.

I’ve always disliked this episode. Why is it called Columbo?

I was going to call you out for being (in your term) “fattist”. I just couldn’t get past all the weight comments in your review. Your later paragraph about Wendt’s casting did make sense, as far as his size being an even more distinctive way to remember someone besides a drink choice and a lighter. That was spot on, but cracks about his weight way before that seemed unnecessary and I felt, distracted me from the wonderfully detailed review.

It’s not necessarily his weight that’s the problem. It’s his sheer size in every direction, height, width too. He is huge by any reckoning, making his casting as someone trying to be inconspicuous particularly troublesome. There were numerous other episodes he could have been cast in where his size wouldn’t have had an impact on the plot itself.

Thah is indeed true, hard for him to disguise himself. I wanted to ask you though, did you notice in the very end of the episode columbo asks fortelli if, hadn’t they agreed on that setup, he’d have actually killed mcveigh?

Fortelli asks columbo why he asked him such a stupid question, but that gives me some doubt he actually was gonna commit a murder, and if columbo doubted that too, that probably makes columbo’s actions less bad here.

I was wondering, how did you interprete that last exchange?

In my opinion, Fortelli was having a little fun with Columbo in the same way Columbo was when he denied he could understand Italian earlier in the episode. Both men pretend to an innocence of sorts, but I have no doubt Forrelli would have had McVeigh killed as he suggested he would during the lunch meeting.

Ahh, I see, thanks for the answer (also to richard weill), I guess I’m more easily deceived by stuff like this than you 2, it makes sense that it was used as a way to exonerate columbo from the actual death threat.

Personally, I regard that exchange as the writers’ attempt to exonerate Columbo from participation in an actual death threat. Let’s show the audience that Columbo didn’t believe McVeigh was in any actual danger when he did what he did. Maybe that will cure the gaping character flaw we’ve just exposed. If so, it didn’t work. Furthermore, if any cop dared participate in a scheme like this, that question would be the LAST thing he’d ever ask. What does it gain you? If Fortelli says no, he’s lying. If Fortelli says yes, you’re sorry you asked. It’s a further highly incredible moment.

My take as well.

A silly bit of trivia – Strange Bedfellows isn’t the first time the careers of Peter Falk and George Wendt intersected. They both made cameo appearances in the music video for the 1984 Ghostbusters movie. I’m not sure the music video deserves any better reviews than Strange Bedfellows, but at least it’s a whole lot shorter.

That’s quiet a deep cut, but you are correct, well done! The music video is a stone cold classic – I’d choose it above Strange Bedfellows any day!

While I tend to enjoy actors playing against type, just the sight of Wendt’s voluminous figure, as Columbophile rightly pointed out, would be enough to thwart his disguise plan. Someone of his size should better take Riley Greenleaf’s route of self-incrimination as a cleverer cover-up move.

Remember this: “It was an honest mistake, sir, and we’re not allowed to get evidence that way”? From “The Bye-Bye Sky High I.Q. Murder Case”? Had the rules changed so radically in time for “Strange Bedfellows”? Because taking the wrong umbrella from Oliver Brandt’s house pales exponentially in comparison with Columbo acting in concert with a mobster’s threat to kill Graham McVeigh unless McVeigh coughs up proof he committed murder.

Of course, the rules have never changed. But evidently, Columbo had. The Lt. Columbo I watched faithfully for 25 years engaged in all sorts of tricks and physically harmless deceits. But he would never have helped stage a threat of mob murder to solve a case, like Columbo does here.

Some dare to compare “Strange Bedfellows” to “A Case of Immunity.” There’s no comparison. The King of Suari didn’t threaten Hassan Salah with murder, or with anything illegal for that matter. Salah was a Suarian national who murdered another Suarian national on Suarian soil (the Suarian consulate). The Suarians had every legal right to try Salah in Suari under Suarian law. Indeed, it is fairly standard, when a diplomat commits a crime overseas, that he be tried in his home country.

The resolution of “Strange Bedfellows” bears no resemblance to any excess by Columbo previously. Even his knowing arrest of an innocent man, Neil Cahill, in “Mind Over Mayhem,” to coerce his father to confess — as offensive as that act was — does not equal the reprehensible way he solves this case.

A lot has been written about how Peter Falk meddled with Peter S. Fischer’s “Strange Bedfellows” script so much, and the casting of George Wendt was so contrary to the character Fischer created, that Fischer took his name off the script and substituted “Lawrence Vail” (the playwright character from Kaufman and Hart’s play “Once in a Lifetime”) instead — what Fischer called “my official don’t-blame-me-for-this-piece-of-crap cop out.” David Koenig discusses Fischer’s dispute with Falk in “Shooting Columbo”; Fischer recounts the controversy himself in his book “Me and Murder, She Wrote.”

While Koenig never indicates who is to blame for the final, reprehensible scene — Fischer or Falk — Fischer’s own account does. And it’s clear that Fischer can’t blame the episode’s offensiveness on anyone else.

Fischer wrote that he “loved the ‘hook’” of “Strange Bedfellows”: “the mafioso wants the killer brought to justice as much as Columbo does which brings them together into an odd an almost unspoken alliance.” Fischer goes on to describe in detail the final sequence where Columbo is about to leave McVeigh to the murderous wrath of mobster Fortelli, concluding: “Hysterical, Graham breaks down and reveals where a vital piece of evidence has been hidden and then we realize that this little one act play has been performed solely for Graham’s benefit. Sounds like fun and it was. At least this one scene was. As for the rest of it, Peter and [director] Vince [McEveety] fiddled and diddled with the structure and the clues to the point where it became incomprehensible nonsense.”

By this account, it is clear that Peter S. Fischer, in his original script, envisioned our hero intentionally participating in a threat of mob murder in order to solve his case. Fischer should be ashamed of himself.

Agree with all of this. The Suari case was superficially similar (threat of execution to force a murderer to co-operate), but here Columbo was trying to get round Salah’s diplomatic immunity, not fishing for evidence he couldn’t get any other way. He already had Salah’s (verbal) confession; it was simply a question of “would you rather be tried in the US, with all our legal protections, or in your own country?”

I agree with just about everything in this piece, and particularly with “… I hold Columbo to higher standards than other run-of-the-mill police dramas. The inherent goodness at the heart of the Columbo character should be sacrosanct.”

Very good assessment/analysis.

I watched this episode wanting to like it, as I was intrigued by the idea of Columbo crossing swords with the Mob. My impressions were that the premise was decent enough (if unoriginal, as the article points out), and the first part of the episode played out OK; however, it all fell apart in the second half. The car chase and the whole business with the dead mice were low points for me; I found both sequences obnoxious and stupid and thought they dragged on far too long.

And as for the ending: yes, I agree that Columbo went way too far. It’s one of those episodes – like ‘Mind over Mayhem’ – where I can imagine the prosecutor tearing his hair out as he wonders how he’s supposed to make a case out of this. I actually can imagine Columbo being willing to team up with mobsters if the circumstances were dire enough; he’s worked with criminals to catch a bigger fish before (e.g. Artie Jessup). But the way it’s done in this episode is neither plausible nor well-executed.

Why was the Bruce Kirby character’s name changed from Sgt. Kramer to Sgt. Brindle? I have a possible explanation (and absolutely no proof that it’s correct).

Writer Peter Fischer basically disavowed himself from this episode, thanks to the horrible re-write decisions made by the production team. Fischer was story editor when the Kramer character was first created and introduced in “By Dawn’s Early Light”. That episode was written by Howard Berk, but perhaps the Kramer character was actually dreamed up by Fischer in his story editor role. Having renounced his participation in “Strange Bedfellows” (as CP notes, it wouldn’t be the first time a Fischer script was desecrated), all mentions of the Sgt. Kramer character might have then gotten changed to Sgt. Brindle. Hey, it’s a theory!

When “Star Trek: Voyager” debuted, it was originally planned to have a character from a “Star Trek: TNG” episode be a part of the crew. The actor Robert Duncan McNeill would have played the role of Cadet Locarno. But if that had happened, “Voyager” would be forced to cut a check for every episode to the writer who created the Locarno character. So instead, they took McNeill, changed a bit of his background for “Voyager”, and wrote the “new” Tom Paris character for him.

This might also explain the seemingly inexplicable name change of Bob Dishy’s Sgt. Wilson character from Frederic in “The Greenhouse Jungle” to John in “Now You See Him”. The character was created for “TGJ” by Jonathan Latimer (per David Koenig’s “Shooting Columbo”), but that writer never again had an association with the show. Presto-chango, ala The Great Santini, a little name switcheroo solves the problem.

Again, no proof on this, just theories. But it’s fun to speculate.

Something you mentioned here comes very closes to how I feel about this episode: only the McBain ones are worse, I think. And I agree wholeheartedly with your verdict, this is just demolishing the character. Columbo would not work with the mob, he just wouldn’t.

In your ranking of the ‘new’ episodes I really don’t get how Grand Deceptions can be ranked lower than this one. Even if you think it’s boring, it’s not nearly as damaging to the series, or to the Columbo character, as this one, right? Can you expand your views on that ranking?

I agree with you, David.

I’ll go one step further. I genuinely believe that a legitimate, spirited debate could be had on whether “Strange Bedfellows” should drop underneath “Murder in Malibu.” Here’s why: focus on the respective mystery premise of each episode. MIM: The prime murder suspect confesses to shooting the victim knowing that police evidence will prove she already was dead when the admitted shot was fired. SB: Columbo can’t prove his suspect killed a mobster, so he stages a scene where the mob boss threatens to kill the suspect unless he proves his own guilt. Which Columbo would you rather watch?

An interesting, if limited, breakdown. Mystery writing alone, I can’t argue with this, but copious other elements go into the total entertainment value of a 2-hour TV movie. SB is bad, but MiM is so poorly presented across the board that even the mystery becomes utterly incoherent. No, MiM heartily earned its place as 69 of 69.

It’s the difference between a horribly executed concept (MIM) and one that died at conception (SB). At least MIM had a chance; SB never did.

I agree with your take on Murder in Malibu and Strange Bedfellows. I’d put MIM over SB even before reading your comment on Peter Fischer’s motivations, because I’m less offended by sillyness and the poor execution of a concept than the deliberate demolishing of the main character.

Besides this, there is the unfathomable and very personal enjoyment factor, which makes me put MIM over RIP Mrs Columbo and It’s all in the game as well, in my own personal ranking that is. With these I don’t like the original concepts, though I don’t despise them the way I dislike Strange Bedfellows.

For this ranking however I think it’s fair to place them higher than Murder in Malibu.

Hi David (and Rich and others), I’ll take this opportunity to address the tail-end of my episode rankings. For me, there are many factors in determining my overall enjoyment of an episode, including the strength of the mystery, plausibility of clues, excellence of writing and direction etc. I also place a heavy importance on the performances and chemistry between members of the main cast – particularly Peter Falk because many a lesser episode has been partly salvaged by the sheer watchability of his performances.

Safe to say, I consider all the episodes in my 4th tier of the new Columbo adventures to be absolute shockers. The dividing line between any of them would be cigarette paper-thin. Why I place Malibu rock bottom is based on such factors as the terrible acting from Stevens and Vaccaro; the pants-fumbling awfulness of Columbo; a dreadful gotcha; lame mid-episode ‘twist’; Jennings’ laughable ability to turn women on by his mere presence; and the DREADFUL production values. The whole episode feels like it was filmed in a hurry with no finesse or care. It feels like a daily soap opera version of Columbo: light, fluffy nonsense to spoon-feed idiots. And even little things, like the use of BAT stock footage instead of crows, enrages me. Such a lazy production is fully deserving of last spot.

With regard to Bedfellows, I believe it to be a bona fide stinker and when I reconsider all the episode positions in the rankings once I’m ready to slot them in amongst the 70s episodes, it may sink even lower. However, while the abhorrence of the careless abandonment of Columbo’s principals enrages me, and McVeigh is a useless criminal, I do gain pleasure from Falk’s performance throughout, which is one of the better portrayals of the new age when compared to how he played the character in the 70s. The scenes between him and McVeigh are well written and hark back pleasingly to his interactions of yesteryear, and Steiger is extremely watchable. It’s for those reasons I would choose to watch it ahead of the episodes below it, if I absolutely had to.

When it comes to Deceptions, the episode’s screaming lack of ambition and utter tediousness renders it so low in my estimations. I do quite like Falk’s performance, but everyone else in the episode is so forgettable (occasionally excluding General Padget), the gotcha is AWFUL and so boringly presented, the comedic interludes abysmal and the Columbo model on the battlefield model the crowning turd. Technically it may be a better mystery than Bedfellows, but for what it represents to me at a time when ‘new Columbo’ ought to have been firing on all cylinders (as William Link promised its comeback season would), Deceptions is such a disappointment that I just can’t rate it higher.

Thanks, CP, for your elaborate answer. I can see why you are so dissapointed in Grand Deceptions. I think what you’ve experienced as ‘forgettable’ was for me watchting Columbo in ‘just another case’. GD is unique in this, there is no other epsiode that makes me feel that way. Even Columbo seems to treat this case as an ‘in-between’, (“Would that have been on Monday, sir?”) if that’s a correct expression. That doesn’t seem to bother me too much. I guess, since I like Columbo even at his most casual I’ve watched Grand Deceptions about as many times as most other episodes (Not Strange Bedfellows). Moreover, and maybe I’ll get some slick for this, the way some Americans live their patriottism and treat guns like toys is humorously outlined during the whole episode. I thought that was funny, maybe because I’m European. So, in short, I see where we see different here.

Make no mistake, I’m no Malibu fan. But you say “a dreadful gotcha.” Compared to Bedfellows? I know nothing about lingerie design, but assuming Columbo is correct about their labeling, proving from the position of the label that someone else dressed the victim is a credible gotcha. It worked in “An Exercise in Fatality.” It’s certainly better than “give me proof you’re a murderer or you’re a dead man!” Not jaw dropping, certainly, but credible. Bedfellows’ isn’t.

I know this is only one factor among many. And I know that I fixate much more on the script than its execution. But production values can only take you so far. As the theatrical saying goes, “You can wash garbage all you want, it’s still garbage.”