Post courtesy of regular contributor Rich Weill. Read his other articles here.

I am generally more charitable toward Last Salute to the Commodore than many. It was meant to be a different kettle of fish, so to speak.

I, for one, applaud writer Jackson Gillis for the way he played with the inverted Columbo mystery formula. He not only gave us a true Agatha Christie-style Columbo whodunit (complete with the traditional gathering of the suspects in the library), but brilliantly disguised his whodunit as a run-of-the-mill Columbo ‘howshegonnacatchem’ for most of its length (specifically, the first 60 minutes of a 95-minute episode).

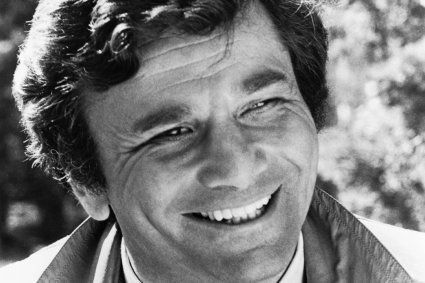

Three key ingredients aided the disguise. First, a veteran Columbo killer, Robert Vaughn (Troubled Waters), was cast as the Commodore’s presumed killer, Charles Clay. Second, Clay engineered an elaborate cover-up, as Columbo villains are prone to do. Third, when confronted by Columbo, Clay acted exactly like a typical Columbo murderer acts: volunteering a bit too much information, offering a few too many theories, and being altogether too helpful. We’ve all seen this routine before.

No, we never actually witness Clay commit the crime, but this wouldn’t be the first time a Columbo murder was suggested, not shown. We never actually see Elliot Markham shoot Bo Williamson in Blueprint for Murder. We presume, but don’t know, that the drugs Emmett Clayton switched in The Most Dangerous Match are what killed Tomlin Dudek. We’ve been acclimated to Columbo’s bloodless, sanitized crimes. For five seasons, we’ve been spared the gruesome details. Gillis makes the calculated gamble that we will assume this is also the case here.

Finding Clay dead in front of his fireplace almost two-thirds through the episode, however, is a surprise that all previous Columbos had reassured us never would happen. When asked “why reverse the storytelling style for that one episode?” Columbo co-creator William Link answered unequivocally: “That was going to be the last show of the series.”

And while Columbo does indeed row off into the sunset at the end, he also makes veiled references to a possible return (“Thought you were gonna quit?” “Not yet. No. Not yet, Sergeant. Not yet.”). Furthermore, Gillis had flirted with this formula break once before, when he revealed in Double Shock that Dexter Paris may not have been Uncle Clifford’s murderer after all. But Double Shock never turned into a full-fledged whodunit in the same way as Last Salute to the Commodore.

Regardless, the formulaic break was refreshing. Mysteries thrive on surprises. What made this particular surprise exceptionally good was that it played on our expectations as regular Columbo viewers. It’s the mystery writer’s form of jiu-jitsu (where you use your opponent’s strength and force of attack as a weapon against him): let the knowledgeable reader or viewer outsmart him/herself.

Less refreshing is the additional stylistic break. According to Mark Dawidziak’s The Columbo Phile, this was director Patrick McGoohan’s doing. “Patrick put his stamp on it,” is how Peter Falk explained the episode’s “different tone.” According to McGoohan, the goal was to take the “fairly well defined” Columbo character “a step farther.”

Fans of The Prisoner also see McGoohan’s handiwork here. According to one comment: “To better understand where this episode is coming from, watch some episodes of Patrick McGoohan’s own series, The Prisoner. What McGoohan has done here is basically shoot a Columbo episode in the style of The Prisoner, which is a pretty weird experiment.”

And yet, on my personal priority list, the soundness of an episode’s story has always topped concerns about style. I’m not especially turned off by the comedic touches. Falk clearly was enjoying himself (as was the case whenever he and McGoohan collaborated). Columbo isn’t realism. Classic whodunits — what Last Salute became — aren’t realistic. Having a little extra fun with an occasional episode doesn’t bother me.

What does bother me, and bothers me a lot, is a bad ending. And while Last Salute‘s final gathering-of-the-suspects-in-the-library scene has its good points (the stencils sequence, for example), the “Commodore’s watch” routine ruins it — and the episode — as far as I am concerned. It’s a wild throw from deep left field. Nothing sets up Columbo’s watch gambit. It isn’t dramatic. And worst of all, Swanny’s single word “T’isn’t” actually proves very little.

Thus, in my view, all the Gillis and McGoohan cleverness went to waste because no one could provide a better gotcha.

So here is what I did. I took the final confrontation scene and rewrote it. I didn’t change the essential story. I didn’t change the murderer. All new clues are mined from the original script. To maintain consistency with earlier scenes, I didn’t even change the lighter style. And while I simplified some of the original dialogue for ease of reading, I retained (even if not in the same order) what I could square with the new material. Rest assured, I did change the gotcha. No more “Commodore’s watch.”

Hunting for an alternative, I shifted my attention from the Commodore’s murder to the murder of Charles Clay. Clay’s murder serves the twist-on-formula plot device — but little else. It’s never even established that both the Commodore’s and Clay’s murders likely were committed by the same person (by, for example, making clear that both victims were killed in an identical manner). A possible motive for killing Clay is mentioned in passing (“your husband began to realize who really did kill your father … that’s why he had to be killed … because he started asking somebody questions”), but this reference is both too vague and too fleeting to be persuasive.

“What McGoohan has done with Last Salute is basically shoot a Columbo episode in the style of The Prisoner.”

So — why was Clay killed? It’s a key question no one looks at closely. I tried to, and suddenly it hit me! Of course! Clay was murdered because Columbo believed he’d killed the Commodore. After all, Swanny’s plan (to inherit the Commodore’s entire fortune) required that Joanna be convicted of killing her father, not Charles.

If Charles were convicted, Joanna would inherit, not Swanny. And Columbo suspected Charles, not Joanna. Swanny had to do something to change that. He had to eliminate Charles as Columbo’s most likely suspect and turn the focus of suspicion back on Joanna. Killing Charles, and leaving a few more “feminine things” behind, was designed to accomplished this.

Why wasn’t this featured prominently in the story? It would have provided something unique in the Columbo canon, as far as I know: someone killed because Columbo wrongly suspected him of murder. Does Columbo take any responsibility for this? Does he even acknowledge that his mistake had fatal consequences? It’s a quandary with real dramatic potential.

It also creates a trail leading directly to Swanny. But it still doesn’t clinch things. It isn’t a gotcha. For that, I looked once again at something not fully utilized in the original script: the “rough draft of a letter [the Commodore] was writing to a big fiberglass factory” that was found in the fireplace grate next to Charles Clay’s body. Would fingerprints on such a document survive? If so, what could they show?

This led me to employ a variation on fingerprint evidence that I don’t believe ever was used in any Columbo episode. It’s also a simple, non-technical, common sense solution everyone can understand. No intricate demonstration of, say, how people tie their shoes (Exercise in Fatality) will be necessary here.

So let’s set the stage. We’re in the Commodore’s library. Doughnuts have been served. With Swanny’s assistance, Columbo has shown Joanna Clay how easily one could impersonate her father. And Columbo gives Sgt. “Mac” Albinsky the word to start the proceedings.

Ready? Begin…

“Mac” Albinsky: Ladies and gentlemen, I felt that — actually, the Lieutenant felt that we’d save time if we all got together here. I’m sure you’re all as anxious as we are to know what happened the night the Commodore was killed.

Sgt. Kramer: And, of course, find the murderer of your husband, Mrs. Clay.

“Mac”: All right. Now, Mr. Clay took the Commodore’s body from the house to the boat. He sailed the boat out passed the Coast Guard station into the ocean, and then somehow he fixed up the boat to make it look like an accident.

Kramer: And then swam home.

“Mac”: Right.

Wayne Taylor: Charles killed the Commodore?

Columbo: Did anyone say that?

Kittering: Really, Mr. Columbo. Charlie certainly went to a lot of trouble if he didn’t murder the Commodore.

Columbo: Yes, he did. A lot of trouble. But then someone murders him. Why? And murders him with a blow from a blunt object, the same as the Commodore. (pause) No, I don’t think Charles Clay, I don’t think he murdered anybody.

Kramer: Unless Mr. Clay realized who really did kill the Commodore. Maybe that’s why he had to be killed, because he started asking somebody questions.

Taylor: Somebody? Who you talking about?

Kramer: Are you kidding? A lot of people would’ve been very upset if they’d suddenly found out what the Commodore was up to.

Kittering: And what’s that supposed to mean?

“Mac”: Everybody knows that the Commodore had been acting a little funny lately.

Kramer: Like, maybe the way he’d built that little yawl to suddenly sail away on for good.

“Mac”: But the Commodore had a lot of unfinished business.

Kramer: Yeah, like painting.

“Mac”: And the will.

Kramer: The boatyards.

“Mac”: And a whole lot of other things.

Columbo: All right, fellas. Give me a minute here, would you? Sergeant, get me those stencils. Give me that brown paper bag. We’ll use that. Mac, help him with the stencils. Hold them up. One, two, three, four, five, six. This is what we found in the boatyard. Stencils, marine black paint. S-A-I-L-S. That’s what it spells. We thought he was putting “sails” on his locker. Get me that other thing. The one with the hole in it. That’s right. All right. Now, we’re standing on a bridge, this fella here and me, and we seen some ducks there and a boat. And then we remembered something. The Commodore, he never painted the name on his boat, did he? No. And that circle there, that became a period. So we had to rearrange things, didn’t we, fellas, huh? So we got a hold of duplicate stencils and some black paint, and we rearranged those letters. This is what we came up with. (displays sign reading “LISA” with a paper bag hiding the end) And that’s what we came up with.

Swanny: He was going to name the boat after her?

Columbo: Well, the only trouble with that, sir, is that her last name is King.

Taylor: And you’ve got an “S” left over. Try again, Lieutenant.

(Columbo drops paper bag to reveal that the full sign reads “LISA S.”)

Kittering: The old boy was gonna marry the kid. Look at that. Lisa Swanson. The old boy was gonna marry the kid. Look at her. She’s young enough to be his granddaughter. (Swanny laughs)

Columbo: Just hold it everybody. Go ahead. Tell them.

Lisa King: They don’t know. Love isn’t just one age or another. Mr. Swanson was the most beautiful man who ever lived.

Joanna: And one of the richest, my dear.

Lisa: But I didn’t want anything from him. (Swanny laughs)

Lisa: Sail the seas with him. I just wanted to make him happy for the rest of his life.

Columbo: Tell them what he told you about his will.

Lisa: I told him I wouldn’t marry him unless he promised not to leave me any money. But he didn’t want anybody else to have it, either. He was sick of parasites. So he was gonna sell the boatyards. And, except for a small trust fund for you, Mrs. Clay, he was gonna give it all to charity.

Kittering: A sad story. Enough to make you weep. (Swanny laughs)

Taylor: Columbo, I —

Columbo: Mr. Taylor, would you kindly sit down? Swanny, be seated please. As a matter of fact, that girl is the only one in this room that doesn’t have a single motive for killing the Commodore or Mr. Clay. Everyone in this room, except Miss King, risked losing their income or their inheritance if the Commodore sold his company and changed his will. Everyone had a reason to want the Commodore dead before he could do any of that. (pause) But what possible motive did anyone have for killing Mr. Clay?

Kittering: Like the Sergeant said, he was threatening whomever killed Otis.

Columbo: Does that sound right to you, Mac?

“Mac”: No, sir.

Columbo: And why not, Mac?

“Mac”: Because Mr. Clay thought Mrs. Clay killed the Commodore. He was doing everything he could to cover up for her. He would never threaten to expose her. Just the opposite.

Swanny Swanson: Maybe he loved you more than you thought, baby.

Columbo: I wasn’t actually thinking about that kind of love. Was I, Mac?

“Mac”: Well, I believe the Lieutenant was thinking about love of money.

Columbo: Exactly. I don’t think Charles Clay was any risk to Mrs. Clay, because he had nothing to gain if his wife murdered the Commodore.

Taylor: Wait a minute, Columbo. Back off.

Joanna Clay: I didn’t kill Daddy.

Columbo: But your husband might have thought you did.

Joanna: The brooch. He gave it back to me the next day, but he didn’t tell me where it came from.

Columbo: Oh. I’ll bet it was right here (points).

Joanna: He asked me such strange questions.

Kramer: Mr. Kittering.

Kittering: What?

Kramer: According to California law, if Mrs. Clay were convicted of killing her father, could she still inherit from him?

Kittering: Oh, of course not. No way. And what’s more, poor old Charlie wouldn’t have been able to get his hands on any of the stuff.

Columbo: In that case, who would benefit the most by the Commodore’s death?

Kittering: Oh, Mr. Swanson, of course. I mean, he’s what we call the secondary heir. In fact, he’s the only other member of the family, isn’t he?

Columbo: Swanny?

Kittering: Swanny, that’s right. Swanny.

Columbo: And if Mr. Clay killed the Commodore, would Swanny still benefit the most?

Kittering: No. Joanna’s not responsible for Charlie’s crime. She’s still the primary heir.

Columbo: And that’s why Mr. Clay was killed.

Taylor: Because of Joanna?

Columbo: (to Joanna) No, not because of you, Mrs. Clay. Don’t ever think that.

Taylor: Then why?

Columbo: Because of me, Mr. Taylor. Because of me.

Kittering: Because of you?

Columbo: Yes. Because I made a mistake. I was convinced Mr. Clay killed the Commodore. I wasn’t supposed to suspect Mr. Clay. I was supposed to suspect Mrs. Clay. But I didn’t, and still don’t.

Taylor: I still don’t understand.

Columbo: Because of me, the killer had to eliminate Mr. Clay as a suspect and turn suspicion back on Mrs. Clay. That’s why Mr. Clay was killed exactly like the Commodore had been killed. And the scene arranged to again implicate Mrs. Clay. How did you describe the stuff they found next to Mr. Clay’s body, Mac?

“Mac”: Feminine things. A handkerchief and a piece of comb.

Columbo: Right, feminine things. What do you think, Swanny?

Swanny: What?

Columbo: You had everything to gain if Mrs. Clay killed her father, but almost nothing if Mr. Clay did it.

Swanny: I didn’t want anyone killed.

Columbo: You’re the only one who knew exactly where Mrs. Clay went that night. Who could have known how upset she was? Who could have followed them and heard the fight between her and her father? Saw the fight. Who could’ve gone in there and killed him when she left the room? Who else could’ve gotten something out of her purse when she was riding in a boat coming back here?

Swanny: Wait a minute, wait a minute.

Columbo: When she was drunk and in a stupor. Who else could have done that?

Swanny: Wait a minute. Wait a minute. Wait a minute. Wait a minute.

Joanna: Maybe that’s when I lost the brooch.

Swanny: Listen to you. You lost that brooch fighting with your father when you killed him. That’s it! It had to be you, Joanna.

Kittering: Mr. Columbo, excuse me. But we’re going around in circles.

Columbo: Yes, sir. I guess that’s true. Except for one thing. It wasn’t just feminine things, as Mac called them, that we found in Mr. Clay’s fire grate. We also found this. (displays a document, charred around the edges, in a plastic evidence sleeve) You remember this, Mr. Kittering, don’t you?

Kittering: Yes, Otis’ letter to the fiberglass people who were trying the buy the boatyard. You showed it to me yesterday.

Columbo: Right. And here’s a photograph of the same letter just as we found it — next to Mr. Clay’s body, face down in the ashes. Notice Mr. Clay’s hands. No gloves.

Taylor: Go on.

Columbo: Did you know that heating up a document in a fire, at least for the parts you don’t burn, doesn’t destroy the fingerprints? That’s what the boys in the lab tell me. Heat makes the fingerprints — what a minute (takes out his note pad and flips through the pages) — fluorescent. That’s the word they used. You can read them under ultraviolet light. And we found lots of fingerprints on this piece of paper. But none of Mr. Clay’s, even though in this picture he wasn’t wearing any gloves. Only the Commodore’s fingerprints, and yours, Swanny.

Swanny: So what? Otis let me read that letter weeks ago.

Columbo: But when you read a letter (demonstrating), your thumbprint is on the front of the page and your fingerprints are on the back. The Commodore’s thumbprints were on the front and his fingerprints on the back. Your thumbprint was on the front and your fingerprints on the back. But both of your thumbprints were also on the back. Only yours. With only your fingerprints on the front. How did those get there? That’s not from reading the letter. Only one thing explains those fingerprints. (turning the page over in his hands) They got there when you were laying the Commodore’s letter face down in the fireplace. Just like in the picture. Next to Mr. Clay’s body. After you killed Mr. Clay the same way you killed the Commodore.

There you have it — my attempt to salvage Last Salute to the Commodore. Whether you think these changes save the episode, I’m sure I’ll read in your comments. At the very least, I hope you consider it an improvement. Then again, you might think — “T’isn’t!”

Richard Weill is a U.S. lawyer and former prosecutor, and a life long Columbo devotee who has contributed several articles to this blog.

Richard also is a playwright whose legal thriller Framed premiered in 2016 to critical acclaim, standing-room-only audiences, a run extended by popular demand — and is the subject of the 2018 book We Open in Oxnard Saturday Afternoon. His first novel, Last Train to Gidleigh (set in World War II-era London), is due to be released later this year.

Read Columbophile’s damning full review of Last Salute here

The weak gotcha is a staple in Columbo episodes. The Commodore’s Watch gag is pretty weak, but no worse that Dawn’s Early Light – “The only way you could have seen the cider was to stand right here at 6:15 am, therefore you killed Mr Haynes”. And hey, look who the star of that episode was!!

A Columbo “gotcha” is evidence consistent with guilt for which the murderer can give no innocent explanation (either because there is none, or because the murderer has wedded himself so completely to a contrary set of facts).

I just discovered this, and I read Columbo’s parts aloud in the Falk accent. I like it. It works. And it really grounds Columbo, who was all over the place this episode.

And a comment to add is the the audio mix is terrible. The background sounds by the docks and shore in particular are so loud, they are annoying and interfere with the general audio mix, How dies this happen??

I try to separate Gillis’ script from McGoohan’s direction.

I’m glad to hear that others found this episode, “Commodore,” dumb, annoying and amateurish. Even Columbo let me down by appearing to enjoy the foolish low-jinks. I thought the lieutenant had better taste. Well, they can’t all be gems, but this was a stinker.

Great job summarizing this episode. The watch ending was weak and confusing. Yours is a better ending to a uneven episode. While I loved the interactions between Columbo and the other detectives, I missed the cat and mouse chase. Overall, it was a fun episode, but not a style that really suits Columbo. P.S. I’ve been binge watching on Amazon. I’ve never seen the ABC episodes.

LSTTC was a one-off. I think it’s fair to assume that no one wanted this structure repeated. In fact, it’s principal attraction (for those willing to see it) is how it subverted the Columbo formula. That only works once.

It doesn’t fix that Columbo is a handsy, clingy, invasive creep thoughout this episode, alas!

Ye put in a worthy effort, but it would take monumental changes to save this turkey, which is worse than many of the 1989 and after episodes. It was a complete wasted opportunity to take advantage of Robert Vaugh’s proclivity to play a Columbo villain. And don’t get me started on the style, McGoogan must have been on LSD while directing this.

Completely agree – the episode is absolutely unwatchable and foreshadows the disastrous decline in American crime tv in the eighties (eg Murder She Wrote, Father Dowling, Matlock and so on). Lord knows what Patrick McGoohan was thinking, but in reality he didn’t cover himself in glory in any of his Columbo involvements.

There seems to be a pattern in the decline of all iconic series – ratings declines precipitate attempts to be trendy/appeal to different demographics – which inevitably leads to even more embarrassing output.

Nowadays we can have a series like the French “Spiral” (started 2006), which can sell in advance round the world, and doesn’t have to worry about ratings in individual markets – but of course this is very rare exception to all the unwatchable American bilge.

Murder, She Wrote is waaaaaaaaay better than this unwatchable disaster.

On top of everything else, the incredibly wealthy Commodore was lettering his boat with cheap stencils and black paint? And if we WAS using stencils he didn’t actually need two S’s.

If you look just above, at the end of the short bio The Columbophile included after my article, you’ll see: “His first novel, Last Train to Gidleigh (set in World War II-era London), is due to be released later this year.” Well, “later” has arrived. My book is now available. If you’re interested, go to:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/0991351282/ or

https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/0991351282/ or

https://www.amazon.ca/dp/0991351282/ or

https://www.amazon.com.au/dp/0991351282/

Or, for more information about the book, go to: https://lasttraintogidleigh.wordpress.com/

Thanks.

Wow, that’s some great thoughts about this episode and a great ending , terrific stuff, congrats, Sir!

Great attempt to change the stinker of Season 5! Yes, this certainly improves the bad ending, especially because of Columbo referring to his fatal mistake. Still, Swanny behaved stupidly during his second killing. Which Columbo murderer would accidentally leave his fingerprints on anything at the scene of the crime? Secondly, the clue is destined to remind the reader of a clue used for “Caution: Murder Can Be Hazardous To Your Health”.

Your comment prompted me to rewatch “Caution: Murder Can Be Hazardous To Your Health.” All I’d remembered about this episode was the business with the hedges (probably because it reminded me of the “two yellow zinnias” in Hitchcock’s “Rear Window”). Yes, there is a clue here about the victim not leaving fingerprints on both sides of a piece of paper (when he supposedly had ripped the sheet from an old continuous-feed printer). I didn’t remember that when writing this article. My clue is somewhat different but, admittedly, in the same general vicinity.

What ruins the ending of the episode, is our expectation of a solid proof against Swanny, because in “Columbo” we got used to solid proof. But since the Columbo formula was here thrown overboard together with the Commodore, the author shouldn’t have had a problem with simply letting Columbo accuse a wrong suspect and then letting Swanny confess and explain what really happened and to visualise the crime in a flashback. Columbo would have been wrong for the first time, the killer would have put it right and this might at least have been funny. Maybe this ending wouldn’t have satisfied us either, but it also wouldn’t disappointed us the way it does when Swanny acts like being caught although Columbo has no proof.

Richard, I fully agree with your take on “Last Salute to the Commodore”. It’s really not that bad an episode, it is just different from the rest. Indeed, the ‘gotcha’ is the weak part of this episode.

Your alternate version for the end is much better, although still not rock solid. Perhaps combining the two evidences: the fingerprint on the letter and the watch – as George Hajdu suggested below – would make a better ending.

In any case, thanks for your efforts to demonstrate how this episode could have been better.

I will never understand why people don’t like the so-called weirdness of this episode. And yes I am a big fan of The Prisoner, too.you get the feeling Peter Falk was enjoying doing this episode and lets face it, Columbo .can start to get dull and routine after a while. .if you don’t like this episode than maybe you should not watch it. Even the worse episodes I will get something out like for instance bye bye high I. Q, try and catch me or Columbo goes to guillotine or the last columbo. To me all of them have something worth watching I think you guys are too serious about it..

Try And catch me and the Bye – Bye IQ murder are 2 of the greatest episodes overall , The 10 poorest of the seventies are Last salute , Dagger of the Mind , A matter of honor , Old Fashioned murder , Murder under glass , Dead weight , Short fuse , Mind over mayhem , Greenhouse jungle and requiem for a falling star . with The conspirators narrowly missing out .

Dagger is not one of my favs but it’s interesting being in another country. I used to hate A Matter of Honor but I think it was only because I was never really paying much attention to it. It’s not really that bad an episode. Honestly what happens is that these episodes become background noise after awhile. I’m ok with that but I guess it’s not exactly fair to the show. 🙁

Another episode came on recently, the one with Lesley Ann Warren and George Hamilton. Definitely not one of my favs. Can you say #metoo? I would always just cringe at how he treated her. Or rather, mistreated her.

If the episode you mean is A deadly State of mind 1975 , I am similar not o a big fan of this one , I am in the club as are many that prefer George Hamilton’s second episode Caution murder can be hazardous to your health , much more enjoyable , a better Murder plot , motive and its full of great comic moments Also one of the better new episodes.

Agreed on both ends.

The Conspirators is one of my top favorites!

I had just asked my brother the other day if there were a Columbo revision who could play him.

He suggested Monk. Who would you suggest?

I have no objection to reviving the general Columbo formula. But an entirely new detective character should be created. Peter Falk is, was, and forever will be Columbo.

Interesting. I agree that the watch was a bad device. The ‘Tisn’t as well. Rewriting seems a little….pointless. But okay.

Pointless? Chalk it up to a repressed, deep-seeded frustration at never having had the opportunity to write a real Columbo episode.

No, I’m sorry, but Last Salute to the Commodore is TERRIBLE, on every level. (And I might add that The Prisoner was vastly overrated !)

But what really sinks Commodore is the absolutely appalling acting – everyone talking v..e..r..y slowly. Peter Falk had become steadily more mannered through the latter seventies, but in this episode he really was quite irritating, (I even preferred his Marlon Brando impersonation in the 1968 Prescription Murder ). As for his young sidekick, he can only be described as truly embarrassing, and I doubt if this actor ever worked again.

Dennis Dugan had a short recurring role over a few episodes of Hill Street Blues.

And Dennis Dugan was married to Joyce van Patten!

I Hate last salute for all the same reasons as most other people but Its not the ending I have a problem with , I can tolerate it to a degree Its just all the nonsense from the start that I cant stand , Lets look to the future Next up William shatner and Fade in to murder , Not one of the greatest of the Seventies but a big improvement on last salute .

Ok so I only read this article do far. I have never liked this episode in general. The daughter is all so whiny and drunk. And the young girl Lisa is freaking comatose. So stupid and so disappointing.

It’s difficult to add perfection to perfection but classic Columbo improves with time and various enhancements.

Sometimes it’s enough to just sit back with a grin and puff a cheap cigar. 😀🖖

loved the alternate ending! thanks!

A good try, to be sure. And most enjoyable as well! But it wouldn’t lead to a conviction. After all, it’s only circumstantial evidence, at best… you can’t hang a man for his having a quirky way of holding and reading a letter. Likewise, Swanny’s original “Tisn’t.” might have referred to the sound of the repaired watch’s replaced mechanism not being quite right – and not recognition of the fact that the watch was still ticking even though it should have remained broken and silent. We still have to come up with a better, sounder piece of evidence to nail that black-hearted blackard Swanny.

Two scenes intrigue me- and make me laugh- Mac and Kramer peering under the sheet at the dead body, for…a long time! (Just what are they plotting under there?) And then they end up with their tushes in the air crawling around on the floor. I was sure McGoohan was high when he directed it. (since being high watching made this episode very funny!)

A Valiant effort. As to the actual episode, the screeching, drunken (she often seems to be faking the distraught drunk act in a pitiful bid for sympathy), scene-chewing overacting by the middle-aged daughter is such a turn-off as to render the episode unwatchable for that reason alone. More ridiculous, albeit less annoying, is the premise that a taciturn, crusty, very very old upper-class patriarch (that’s the type who like to be called “commodore” and in charge of yacht clubs) had a secret marriage to a wan, listless, depressive and nearly wordless quasi-hippy yogini chick who’s young enough to be his granddaughter (or even less likely, that she would marry him and sail off into the sunset)…she looked and acted more like a sanitized Manson Family member than someone who’d be interested in any involvement in yachts or a yacht club, much less in a romance and marriage (and presumably sex) with a doddering reactionary grandad-figure. At least the girl’s non-materialism rings true. Otherwise, Implausible and Ludicrous. It would have been more interesting if the Commodore had found out Lisa was his lovechild from a secret affair with his maid, and secretly changed his will in her favor. A 40-something widowed waitress with a heart of gold from the yacht club dining room would be somewhat more believable as his secret wife. I do feel sorry for the Robert Vaughan character, both before and after his murder. But I know! How about if Swanny secretly knew that his brother had secretly married Lisa, whom Swanny himself was secretly in love with! Swanny secretly killed his brother so Lisa would be free to marry him! Makes about as much sense as the actual plot.

Greta point: Saved me the time of writing it. The very idea of an 80 yr. old man falling madly in love with a teenager is far-fetched enough. To make it somewhat plausible there must at least be something in their natures that would make them attract and be willing to overcome the age difference. In this case, everything the writers show us about the nature and lifestyle of these two characters indicates that they would be the very last two people on earth to fall in love even if they were the same age, let alone 60 years apart.

RE-posted on twitter @trefology

As I said elsewhere, I was totally hoodwinked by the presentation of the original murder cover-up and flabbergasted by Charles Clay’s later demise. I was hooked right up to the drawing room scene. The horrible gotcha completely destroyed the episode for me, as it did for Mr Weill. His gotcha is much better, though still not completely satisfying. What if, after reading the letter, Swanny turned it over and placed it face down on the Commodore’s desk. All the actual fingerprints are then explained. If the letter is a plant by his murderer, Clay’s prints would not be on the letter.

The episode still has other flaws. The relationship with Lisa King is very poorly developed. We should have been shown at least one scene in which the crusty Commodore visibly softens in Lisa’a presence, even if the actual relationship remained obscure. Perhaps, we might initially be led to believe, that he saw her as the engaging, sober daughter he wished he had. The revelation that the relationship was actually romantic–it was never clear, or even plausible, that it was physical–would then come as an additional twist.

Clearly, that would have required a much more extensive rewrite, one that requires skills I do not possess.

If you are reading a letter and want to leave it face down on a desk, you turn your hand over without repositioning your fingers. And you certainly wouldn’t hold it upside down with both thumbs on the back. The latter bespeaks the kind of careful, intentional placement at floor level such as we have here.

Then why didn’t Swanny just use that maneuver when planting the letter at Clay’s residence? Normally, you would glance at a document before you file it (or plant it at a murder scene). People fidget. They move things from hand to hand. Perhaps he turned it over before handing it back to the Commodore.

No. Swanny’s fingerprints are inconclusive.

I do agree that Columbo himself might very well present the fingerprints on the letter as conclusive evidence. This is one of Columbo’s blind spots. For him, there is only one way that a “normal” person would do this or that. I am not talking about behavior that simply raise his suspicions. That’s what makes him such a great detective. It’s when these quirky prejudices are central to the gotcha that I get bothered. It’s why many of Columbo’s detainees would get off either at trial or on appeal. Twelve people would have to buy into the Lieutenant’s thinking–beyond a reasonable doubt.

Now there’s a High Concept for a series. Columbo: Law and Order. We take each Columbo case and see how the subsequent trial unfolds using only the evidence developed in the original episode.

Some of his targets are clearly toast. I think everyone in Season 1 (including the pilots) gets convicted, either because the gotcha’s are good on their own, an accomplice rats him/her out, or the murderer confesses, Perry Mason style, when confronted. As it was in the Mason series (which I also love), the third of these is frequently just lazy writing, practically an admission that the gotcha itself is too weak to stand up in court. When the gotcha is really good, the murderer usually just sputters or glowers.

Beginning in Season 2 and getting worse thereafter, the “conclusive” evidence presented by Columbo is often easy to discredit and the Perry Mason admission (or psychotic breakdown in Dagger) becomes more and more essential to any conviction.

Very good ending, and also fully reasonable, methink. But just one more thing! I would insert also the Commodore’s watch scene, and therefore combine the original ending with yours. Just insert the watch scene at the right place.

Swanny negatively identifies the watch from its ticking, that it is impossible to be the original one as it was destroyed. Columbo then tries to charge Swanny, but he declines, also Kittering adds that this isn’t sufficient evidence. But the fact is, from now on, that Swanny is _really_ suspicious. So, this is just a rather weak evidence, also indirect, but in font of many witnesses.

THEN comes the other evidence, the letter and the reverse fingerprints. This way the weak and the medium evidence strengthen each other.

What do you think?

Many thanks to m’man Rick for another astute and fascinating contribution. Save a major rewrite and reshoot without the weirdness, I don’t think Last Salute could ever be salvaged, but your alternative ending would have boosted the gotcha no end, and given some clout and meaning to what was such an anticlimactic finale.

I don’t mind this episode but I think your ending would have definitely improved it! I enjoyed reading it and I can see it playing out in my mind. I’m going to watch it now!