In response to my “second opinion” review of Dagger of the Mind, one commenter posed the question: “As a former prosecutor, how many of Columbo’s cases would actually hold up in court?”

I asked Columbophile if I could write another post for his blog setting forth my answer. He agreed, so here we are. We decided to use only the episodes he had reviewed thus far, so as not to interfere with future reviews (taking us up to Requiem for a Falling Star).

Because the episode that prompted this question, Dagger of the Mind, is “solved” by Columbo planting false evidence in order to trick his suspects into confessing, I think it’s reasonable to infer that the question quoted above is principally directed to the trickery issue.

Are police permitted to trick suspects into confessing? The answer is yes, as long as the confession remains voluntary and reliable. And that’s certainly true of suspects who are not in police custody and thus, for example, have no right to receive Miranda warnings.

The problem in Dagger of the Mind isn’t the trick, it’s the confession. Lillian Stanhope says: “He was mad. Don’t you see? … He didn’t know what he was doing. … And Sir Roger, that was my fault. … It was an accident.” What is she confessing to – an accident? Furthermore, by law, Lillian’s confession is inadmissible against her husband; and since Nicholas Frame was meanwhile babbling incoherently, we still have no proof against him. Nor proof of the Tanner murder. Hopefully for the sake of the case, when everyone settles down in an interview room at the Yard, the Frame-Stanhopes will be more forthcoming.

In other words, the ever-present Columbo will-it-hold-up-in-court issue is this: What has Columbo actually proven?

Several weeks ago, Columbophile and I had an exchange about this very question regarding The Most Crucial Game. In my view, Columbo disproved Paul Hanlon’s alibi (that Hanlon was in his stadium box at the time of the crime): the clock in his stadium box did not chime during his call to Eric Wagner although it chimed, chimed loudly, and chimed on time, an hour or so after the murder when Columbo first visited Hanlon’s box. But disproving an alibi is not the same as proving guilt. The one does not necessarily follow from the other.

“Columbo’s job is to solve apparently perfect crimes. Sometimes these solutions, legally speaking, are slightly imperfect.”

Here you do have the added fact that Hanlon asserts, reasserts, and re-reasserts his alibi over and over again (including right before we hear the missing chimes). Proving that Hanlon lied to the police repeatedly about a critical issue gives untold additional power to the prosecutor’s other circumstantial evidence against him, and could be decisive here. But in a different case, simply disproving an alibi might not be enough. [Note: To convict Hanlon, the prosecutor will also have to ensure that the jury understands without hesitation that motive is not an element of murder, and thus need not be proven.]

Ransom for a Dead Man is an excellent example of proving far less than we are led to believe. Even assuming that the serial numbers on the $25,000 in cash that Leslie Williams gives her stepdaughter Margaret matches some of the marked $300,000 ransom money, how does this prove that Leslie murdered her husband? All it proves is that she never dropped the ransom money from her plane as she claimed, but kept it for herself.

A search warrant for the Williams home undoubtedly will uncover the other $275,000 in marked ransom money. So we will have proof that Lesley used the purported kidnapping of her husband to unlawfully break her stepdaughter’s trust and steal the contents of Margaret’s trust account. But is that enough to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Leslie killed Paul Williams and arranged a fake kidnapping?

Of course, proof beyond a reasonable doubt does not require a “smoking gun.” Many murders are proved circumstantially. In fact, circumstantial evidence can be more reliable that direct evidence, i.e., eyewitness testimony. Eyewitnesses are often wrong. A piece of circumstantial evidence may not prove a lot in isolation, but it usually is what it claims to be. Most Columbos don’t focus on the totality of the circumstantial evidence; they center on the one “pop” clue (as Peter Falk used to call it) that proves the murder case beyond all doubt. Forcing Leslie to reveal her possession of ransom cash doesn’t actually do that.

“Are police permitted to trick suspects into confessing? The answer is yes, as long as the confession remains voluntary and reliable.”

Some clever prosecutor might argue that, at the very least, it proves that Leslie intentionally dropped an empty satchel. If the kidnapping was real, Leslie must have known that dropping an empty satchel would certainly result in her husband’s death. Thus, she intentionally caused his death by this act alone. But this theory requires proof that Paul Williams was alive at the time of the ransom drop – and he wasn’t.

When confronted with the ransom money, all Leslie says is: “You’re very lucky, Lieutenant. No, congratulations, you’re very smart.” Is that confessing to murder? No. It may be a tacit admission that Columbo’s nailed her doing something wrong, but fraud and theft are crimes, too. It’s not a murder confession.

The episode Columbophile reviewed most recently, Requiem for a Falling Star, has a similar problem. Columbo may have established that Nora Chandler faked Al Cumberland’s drowning – and we can presume that Al’s body will be exhumed from Nora’s back garden – but where’s the proof that Nora murdered Jean Davis? Because “Jean knew” (Nora’s only so-called confession about the Davis murder)? What does that prove?

Is there even proof that Nora murdered Al Cumberland? Here is Nora’s entire confession about killing Cumberland: “We had a hell of a fight. We argued, fought, and I – I struck him with a bottle. And he – I-I-I panicked. And I buried him out there.” How does a prosecutor disprove self-defense from that? Hopefully, the autopsy results will establish something less equivocal.

Tough cases to crack?

At the end of Etude in Black, Alex Benedict sounds like he’s ready to make a full confession. Let’s hope he does because, to this point, Columbo’s case rests on Janice Benedict remembering the then-insignificant act of Alex not putting a flower on.

Recalling a memorable event is one thing; recalling something insignificant at the time is hardly ever certain. Incidentally, Alex’s whispered “I’m guilty” to his wife is likely barred from evidence under the spousal privilege. I’m amazed that Columbo has no crime scene photos showing Benedict’s flower under Jennifer Welles’ piano before Benedict returns to the crime scene – but no photos are ever mentioned.

Speaking of witnesses, the solution to Lady in Waiting depends entirely upon Peter Hamilton’s recollection of which he heard first: gunshots or the alarm. If Hamilton equivocates on the stand, the case is sunk. Of course, had the alarm sounded first, Hamilton would have heard the shots through the alarm (which he didn’t). So it isn’t merely a “which came first” question, which should help the prosecutor’s case. But it’s still what we call a “one witness case,” and those are tough.

Dead Weight is also very much a one-witness case (with corroborating ballistic evidence, as well as corroborating excited utterances made contemporaneously by Helen Stewart to her mother). But if Helen suddenly were to recant out of renewed affection for General Hollister, where’s the proof that Hollister was the shooter? His gun certainly was the murder weapon, but in whose hands?

Prescription: Murder not only depends on Joan Hudson’s continued willingness to cooperate but, because she is an accomplice, the prosecution also needs persuasive evidence to substantiate her credibility. The prosecutor is helped to no small degree by Dr. Flemming’s narcissistic conversations with Columbo where Flemming pontificates “on a theoretical basis” about “this hypothetical murderer.”

Does Flemming really believe that, with this disclaimer, his statements will be kept from the jury, and that the jury will not be permitted to infer guilt to the extent that his “hypothetical,” “theoretical” statements dovetail with other evidence?

Columbo himself will be the key witness in Suitable for Framing. How will the Lieutenant justify being in Dale Kingston’s home – and sticking his hand in Kingston’s private property? Yes, his gloved hands prove that he did not put his fingerprints on the Degas pastels after the other detectives recovered the paintings from Edna’s linen closet. But what proves that Columbo did not find and touch the Degas paintings before lawyer Frank Simpson demanded the search of Edna’s house?

That will certainly be Dale Kingston’s attorney’s line of defense – and it will all depend on Columbo’s performance under rigorous cross-examination. The significance of those prints (upon which the prosecution’s case hinges) will be a difficult thing for the jury to follow even under the best circumstances. Columbo will have to exclude other possible sources of those prints. Hopefully, his police reports are more detailed than the cryptic scribblings in his notebook. If not, defense counsel will have a field day with Columbo on the stand.

Confessions by conduct

A few Columbos end in confessions by conduct. That can be very powerful evidence. As a prime example, there’s Brimmer retrieving the contact lens from the trunk of his car – and then trying to throw the contact lens away – in Death Lends a Hand.

But wait a minute. Wasn’t the lens a phony, and didn’t Columbo both break into and tamper with Brimmer’s car in order to plant it? Yes, but Brimmer made an independent decision to search for and dispose of the lens. His independent actions attenuate his conduct from anything Columbo did beforehand.

There’s also Roger Stanford’s dismantling the cigar box in Short Fuse. Assuming that the eyewitnesses can convey the conduct to the jury as potently as it appears to us on the screen, the prosecution will do just fine.

Greenhouse Jungle is a good example of the power of circumstantial evidence. Three matching bullets – one from the victim’s body, one fired into the victim’s car, and one admittedly fired by Jarvis Goodland – is very strong evidence that all three were fired by the same person, namely Goodland. Fortunately, ballistic markings are fairly indelible, so Columbo’s habit of wrapping critical evidence in an old hanky and stuffing it into a raincoat pocket full of who-knows-what probably won’t affect the prosecution’s case in this instance.

Which brings me to my all-time favorite Columbo: Murder by the Book. The case against Ken Franklin for the murder of James Ferris depends on proving that the murder described in Ferris’ notes (which Franklin admits “is my idea, the only really good one I ever had,” and that “I must’ve told it to Jim over five years ago”) is, as Columbo tells it, “the part you used, practically word for word.”

We know that’s true because we saw the Ferris murder. But how does a prosecutor prove that the actual murder was committed “practically word for word” as Ferris’ notes described: “A wants to kill B. Drives B to a remote house and has him call his wife in city. Tells her he’s working late at the office. Bang, bang”? What’s the proof that Franklin wanted to kill Ferris? What’s the proof that Franklin drove Ferris to a remote house, or that Ferris called his wife to tell her he was working late at Franklin’s suggestion? To me, that’s the problem with proving Columbo’s theory in court. To prove the theory, you first have to prove that Franklin murdered Ferris. And if you can do that, why bother with the theory?

Columbo’s job is to solve apparently perfect crimes. Sometimes these solutions, legally speaking, are slightly imperfect. What do you expect? That Columbo is going to catch the killer in the act of burying his victim? Oh, that’s right: Elliot Markham in Blueprint for Murder. Yes, Elliot’s a dead duck in court. We can be fairly sure of that.

There you have it. Two pilots and the first dozen Columbo episodes. Many different types of solutions, each with its own challenges, more or less, for the prosecutor. But the jury ultimately will decide. Jurors are people like you. What’s your verdict?

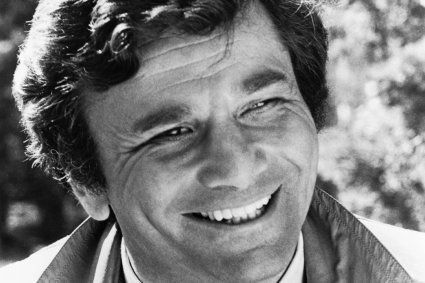

As well as being a long-time Columbo fan, article author Richard Weill is a lawyer, playwright and former prosecutor based in New York.

Read Columbophile’s unscientific second opinion on the fate of the Columbo killers here

The evidence on Franklin is all circumstantial, although strong in motive and his lack of alibi. Victim’s body just turns up on his front lawn one night and he expects the police to believe that? Typical audacity of the Jack Cassidy episodes that makes them so much fun.

What should sink him is the 2nd murder. Local store owner that he denies knowing “drowns” on a boat in the middle of the night on the same lake as his getaway cabin. And she has this book that he personally inscribed to her. Bank records here are also incriminating…

Greenhouse Jungle – this case won’t even make it to trial. Unless Jarvis Goodland has the world’s most stupid lawyer, he has nothing to worry about. Columbo searches the greenhouse and uses a metal detector to find the bullet which, supposedly, shows Goodland’s gun is the murder weapon. He conducts the search without a warrant and against Goodland’s wishes – he asks him several times to desist with the search and leave. Any evidence discovered or collected during the search is inadmissible in court. There is no other evidence implicating Goodland and a grand jury would take ten minutes to throw the case out.

I’m STILL iffy on Hanlon. Even with the chime, as he could claim that 1. The clock wasn’t working. 1A. Something wasn’t making it chime, he mussed with the gears after the game, and that resolved it. 2. He moved the clock during games and moved it back when they were over. 3. He was in a hurry and tossed his jacket over the clock at the start of the game, which obviously muffled the chime.

They still have no murder weapon. Theorizing it was ice is just that.

Even if they take the testimony of the young girl, that proves that an ice cream truck was in the area, not that Hanlon was driving it. It’s curious, but it could also be pinned on a random employee taking it out on a joyride. That’s a really random explanation but you get my point. There’s no witness who can testify they saw Hanlon drive it.

Also, the hose could have been used to wet down the sidewalk to hide footprints, but it also could have been used by Eric Wagoner to wash off bird droppings or dirt from the sidewalk that he noticed before he jumped into the pool. There are a number of explanations beyond just “He wet the sidewalk to hide his prints.” We believe in the conclusion because we witness it.

If the prosecution argued Eric was lazy and would have had his lawn staff do it, well, they weren’t there, as was established, so, your honor, Eric must have done it himself.

And then there’s that pesky issue of a motive. There’s just not a clearly-defined motive. Sure we, as fans, in the comments section have offered our own ideas. Hanlon wanted to run the team alone. Or Hanlon wanted Wagoner’s wife. Or Hanlon wanted both. Yet those are all theories. Nothing in the episode gives us any true motive why Hanlon would do what he does.

Based on the episode, it seems like Wagoner is very hands-off when it comes to the team, and for all intents and purposes, Hanlon is running it his way already. That could easily be argued by the defense. Why would Hanlon murder a man to get a position he already has? Yes Wagoner joked about firing him, but there’s no point in the episode where Wagoner gives any serious statement to say he actually would. Cunnell is meddling, but not super seriously.

As for Hanlon wanting the wife…That doesn’t really jive either. Hanlon doesn’t do anything overt on that end. He doesn’t profess an attraction, nor really hint that he’s attracted to her at all. He’s comforting around her, but again, that could easily be explained as him wanting to make sure the widow Wagoner views him as an ally and a friend and keeps him managing the team indefinitely.

I love the episode still, cause Culp and Falk are fantastic in it, but to me, even the circumstantial evidence presented isn’t strong enough to ensure Hanlon’s conviction.

Hanlon had ample opportunity to offer one of these hypothetical explanations when he was first confronted with the missing chimes. None is something which, if true, he was likely to forget. But he didn’t mention any of them (and not because he was invoking his right to remain silent). If he tried to later, it will look like exactly what it is: a long after-the-fact concoction. No one will buy it.

As I said originally, you still need affirmative proof. But sometimes a discredited liar has a tough time getting a jury to focus on anything else.

Love this. Are you guys going to review the other episodes at some point?

It’s fun to see how far the cases would go, Columbo has some other shaky ones – I think his badge maybe on the line in ‘Double Exposure’ (maybe not his badge, maybe just some time on traffic duty :)). The more I watch them, the more I think he’s not concerned if they get convicted or not – he’s like the inspector in Inspector Calls. Some kind of manifestation of their conscience that haunts them till they confess. Maybe a bit deep, I dunno.

I’m willing. My concern with the legal aspects of these cases is less with the propriety of Columbo’s conduct (although that is an issue on occasion) and more with: what has Columbo really proven? Take the next episode after the ones covered here — “A Stitch in Crime.” Mayfield killed two people, Sharon Martin and Harry Alexander. Does Columbo prove that Mayfield committed either of those crimes? He proves that Mayfield used dissolving suture (disguised as permanent suture) to “repair” Dr. Heideman’s heart. That may be enough to prove Mayfield tried to kill Heideman. But Heideman is still alive. Does this evidence prove either murder?

Right, I guess he generally just proves that it could be done, and not that the baddie did it – like your Murder By The Book example. Also sometimes the plots are so entertainingly convoluted that either a jury would get lost or they’d look at the charming, usually rich baddie with top defence lawyer and think, ‘hmmm, I can’t see this successful, top-of-the-pile football team manager dressing up as an ice cream man, sneaking out a packed stadium, taking someone’s truck miles away…’.

Most of the baddies would be better off killing their victims with a crowbar in a random carpark – they just reduce the amount of suspects with their clever schemes – that said, there wouldn’t be a show if they did that so I’m glad they don’t haha.

Although I don’t give much credence to this “his lawyer will just say …” defense. Lawyers can say whatever they want. A lawyer’s rambling is not evidence.

The genius to me is in the little things he catches, and after watching a lot of true crime, that seems to be the case in a lot of situations. In one true crime show I saw, a man who killed his business partner claimed the partner came over unexpectedly…long story – but the tipoff was that the security camera caught the partner’s arrival, and someone (the killer, the only guy in the house) – had lifted a tiny portion of the blind to see him in the driveway. In another case, it was a real Perry Mason moment. The defendant’s blood expert – the defendant’s, mind you – was asked by the attorney how the defendant could have gotten blood way up in the inside of his sleeve. The expert said, well, the only way that would have happened is when he leaned over to kill her.

I found the gotcha in Short Fuse pretty unconvincing, tbh. They are together in a small cable car and talking about explosions and bombs in cigar cases, and then Columbo produces a cigar case and is “surprised” that the killer tries to get rid of it?

He would probably have done the same even if he wasn’t the killer. Heck, I would do it if someone trapped me in a situation like that.

The better question might be would Columbo really have brought a cigar case that might have had explosives in it on that cable car knowing that explosives could have gone off even accidentally?Yes Columbo might have done anything to nab a killer but he would have possibly put himself or other people in danger to do it?I don’t think so.

But (a) Columbo knows the cigar box really has no explosives, and (b) the story Columbo is telling Roger Stanford is that, given the recovery of an intact cigar box, thrown clear from the death car, his earlier theories about the cigar box causing the explosion are now clearly wrong: “Now, it turns out to be just an ordinary cigar box.” So no one should have had any ostensible reason to fear the cigar box. Except that Roger Stanford knew there was only one cigar box in his uncle’s car, and that box was loaded with explosives. No one but Roger. To me, the solution fits perfectly.

very nice submit, i definitely love this web site, keep on it

In Requiem For a Falling Star Nora Chandler told Columbo that Jean Davis knew about Nora’s husband been buried under the fountain.So that would have given Nora a motive for wanting Jean dea

Also prosecutors i’m sure could offers some of the killers that Columbo caught plea deals.Plus Columbo’s job is to find the murderer and once he’s done that it’s up to the prosecution to prove the case.

Prosecutors only have the evidence the police provide. If prosecutors can’t prove their case, the police didn’t do their job.

I disagree. The beginning of the case is after the arrest is made and the crime is turned over to the DA. That’s when witnesses are extensively interviewed, and the DA comes up with a theory of the case. The DA has their own detectives. If they don’t think they have a case, they won’t press charges. Columbo isn’t really about that – it’s a cat and mouse game between Columbo and the criminal. Whether or not the person gets off, they did the crime, and Columbo knows they did it. That’s what the series is concerned with.

Actually, Columbo is all about proving that the murderer committed the crime. Maybe it’s not proof in the strict legal sense, but it’s compelling dramatic proof nonetheless. Proof for which the killer has no ready, innocent explanation. Because if Columbo episodes ended when “Columbo knows who did it,” some shows wouldn’t last a half-hour. In how many episodes do we learn that Columbo knew who did it minutes after the crime? “Murder by the Book,” “Troubled Waters,” “Mind Over Mayhem,” “Murder Under Glass,” etc., etc. But he didn’t have proof. The drama is about painting the killer into a corner, cutting off theories of innocence, and finally finding the one piece of evidence (which can be an action by the killer) that the killer can’t explain.

Plus there’s no statute of limitations where murder is concerned.So even if a DA decided not to press charges because he or she thinks the evidence Columbo has collected isn’t enough to get a conviction the case isn’t closed.The investigation could continue

Maybe they could just show the juries the ‘Scene of the Crime’ like in Police Squad?

“But what proves that Columbo did not find and touch the Degas paintings before lawyer Frank Simpson demanded the search of Edna’s house?” How would Columbo know where the paintings were? He would’ve had to suspect that they were planted there somewhere but he’d have to find them between the time Kingston planted the paintings and the police came to search the house. Too many things would have to go perfectly for that to happen.

This is a terrific article on the legal perspective of Columbo’s cases and I always refer people to the link to it whenever somebody mentions “Oh, in real life, Columbo’s murderers would get off the hook based on the evidence in those shows.”

obviously(Colombo) has lost a lot of court cases. Patrick mcgoohon survived 4 episodes and William shatner 3(I think) are proof of that.

Great post! And one thing that’s almost always significant: these aren’t perfect murders. The murderers only THINK they’re perfect murders. That’s usually their undoing. Some of the best episodes — “Any Port In A Storm” comes to mind — are the exact opposite, too. The killer knows that he was sloppy and that if he avoids arrest it’s largely going to be because of dumb luck. Donald Pleasance seems like he’s trying to buy as much time as possible, but overall he’s waiting out the clock.

As Columbo said in one of the later episodes, he always has an unfair advantage in these cases. It’s the perpetrator’s first murder. It’s Columbo’s 500th.

That’s what gives “A Trace of Murder” (1997) a neat twist: this time Columbo is up against a police forensics expert (David Rasche), who should be able to avoid making those little mistakes that Columbo notices, because he’s like Columbo and he’s seen hundreds of these things.

Of course, even though he’s the crime scene investigator on his own crime, he still makes mistakes. IIRC this is another case where a /Columbo/ villain being a non-smoker leads to his downfall. If /Columbo/ teaches us anything, it’s that if you’re going to use cigarettes or cigars to create false clues, be a smoker; otherwise, don’t risk it! It’s way more complicated than you think!

This was really fun to read. I’ve always wondered about the aftermath of the cases. Thanks for sharing this with us.

I’m pleasantly surprised that Columbo’s arrests ( at least those covered here) have odds for conviction that are as good as the article makes it appear. Yay, Columbo! This was an enjoyable post. It’s always a pleasure when an expert can write about his field of expertise with a clarity that allows anyone to reasonably follow along. Thank you.

Let’s be honest, no TV crime would make it too a jury. There’s always issues with the evidence.

If two CSI acted like the TV ones, the evidence would either be destroyed or contaminated beyond use

True. But there is also the issue of contaminated evidence.

Yes, Columbo handles evidence rather unprofessionally (as I mention in the post). However, in the episodes considered here, I don’t recall that this was ever a significant factor. It certainly will be later (see, e.g., the cheese and chewing gum in “Agenda for Murder”).

Excellent post Richard – I have sat on a jury and know how hard it is to find someone guilty. Quite rightly the onus is overwhelmingly on presumed innocence.

There are one or two of the murderers who I wouldn’t mind seeing get off – maybe Nora Chandler and Abigail Mitchell?

I am not sure about Nora, but I always thought Abigail got off because her lawyer argued jury nullification. Also, in Lovely but Lethal, the first murder was manslaughter and her lawyer could argue self defense and he might have gotten her off. Her mistake was the second murder. The Robert Culp-Ray Milland one, that was manslaughter. The most important thing in any murder case is the confession – and the police often get a confession out of people who didn’t even do it, if you watch the ID channel like I do. It’s very hard to convince a jury someone admits to committing a crime that they didn’t commit.

Always keep in mind that the investigations don’t begin with the arrest. The arrest is just the beginning. Columbo only has to prove that it’s more likely than not the accused committed the crime. The prosecuting attorney’s office takes over from there and can subpeona documents, interview witnesses under oath, and obtain additional search warrants. All of this can take several months before the case starts to go to trial. So yes, the evidence can be iffy at the time of the arrest. but by the time the criminal justice system does its job the case can be air tight.

I think you mean: “investigations don’t end with the arrest.” While that’s true, it is also true that once an arrest is made, prosecutors have a fairly small window of time within which to make a case better. Good police officers don’t arrest simply because minimal probable cause exists. They arrest someone they are fairly sure the evidence is compelling enough to convict. Yes, the investigation will continue, but one cannot gamble on making a weak case strong once formal proceedings begin.

Yes, you caught my typo. Prosecutors have as much time as the Court will allow. The defense can always opt for a trial to begin sooner rather than later. Regardless, once Columbo makes the arrest, a lot more evidence will be gathered by the time the case goes to trial.

This is a great post, and it’s a topic that I’ve ended up arguing with my girlfriend about a lot (who happens to be a lawyer). The particular argument came from the ending of “Exercise in Fatality” when she maintained that Columbo’s solution of the tied shoes was entirely circumstantial. I’ve always liked that solution myself, mostly because Robert Conrad is just SO arrogant throughout.

Your point about Suitable for Framing is also a good one (though Kingston DID give Columbo the key to his place, so there’s that). I’m also willing to overlook the issue of the prints simply because I love the reveal of the gloved hands so much.

You’re quite right about the keys. What Kingston told Columbo at the time was this: “You may look at anything you wish. You can snoop in all of my closets. You can peek under the beds. You won’t find any stolen paintings. … Here. Would you like the key to my apartment? You may simply leave it under the mat when you leave. … Go ahead. I insist. See what I live like.”

Did that authorize Columbo to camp out indefinitely in Kingston’s apartment — or just “look at anything you wish” and then “leave [the key] under the mat when you leave”? Generally, courts scrutinize carefully someone giving police consent to search, and view the terms of that consent narrowly.

As I said, it will depend on Columbo, testifying as a witness and subject to cross-examination, to justify what he did.

Richard,

Thank you for another insightful, entertaining piece. I’m going to jump ahead to the end of the series and inquire about “Murder Under Glass.” Columbo reveals the “hard evidence” of the poisoned wine to Paul Gerard, who sinks into submission and confesses. However, if Gerard were to grab the glass and fling it across the kitchen, to what degree would destroying the so-called hard evidence improve his chances of acquittal? Thank you for any clarification!

Flinging the glass across the kitchen wouldn’t help one bit. The forensic team can still obtain samples of the poisoned wine that would be left on the walls and/or floors once the glass breaks.

And, if my memory serves me correctly, Gerard poisoned the entire wine bottle (with the poisonous opener), not just the glass. So breaking the glass wouldn’t eliminate the evidence in the bottle.